Varieties of Indian tomahawk ax

Although the tomahawk for ordinary people is associated with the so-called “Missouri axe,” the type of tomahawk could be different, in particular:

- Celts. The very first iron tomahawks, which were driven into the handle with a butt. The same group includes celts with a point, more like klevets;

- Ear tomahawks. Exactly those that were advertised by cinema and books about Indians. They were otherwise called “Missouri axes” and were a traditional form of an ax with an eye. Used for combat operations, very rarely in everyday life (mainly for quickly cutting up carcasses);

- Pipe tomahawks. They could be of any type, but they had a special feature - a channel along the entire length of the handle. Often richly decorated, they were rarely used in battle due to the hollow handle. Their main purpose was in diplomatic ceremonies between tribes, often given as a sign of friendship;

- Esponton tomahawks. They were a mixture of esponton and axe. Most likely, they were remade from espontons taken in battles with settlers;

- Halberd tomahawks. They were brought from Spain and were either shortened halberds or hatchets made according to the same pattern. The rarest variety, the North American Indians had them mainly among the leaders, emphasizing their status.

Celtic tomahawk

Pipe tomahawks

Esponton tomahawks

Halberd tomahawks

Types of Indian Tomahawks

- Celt

. It is one of the first models. Its shape resembles a similar tomahawk made of stone. These products did not have special holes to facilitate putting the working part on the handle. The blade was inserted into the shaft using a sharpened butt. This Native American tomahawk was widely used between the 16th and 17th centuries.

- Celt with a point.

The blade of this Indian hatchet has the shape of an elongated triangle, passing through the shaft so that one of its sharpened corners is located on the back side of the ax, forming a point. The design of the tomahawk gave the impression that the steel plate had split the shaft. To securely fix it, special bindings were used. - Missouri type

. This Native American tomahawk was used until the 19th century. It was distributed along the Missouri River. The working part of the ax was placed on an ordinary ax handle with an eyelet. The blade was not hardened and was of enormous size. Its surface had various slits and holes for decoration.

- Tubular type

. Tomahawks of this type are the most common. A special feature of the tubular hatchet is the presence of a special through channel in the shaft, which stretches along the entire length of the handle. In the butt part of the tomahawk there is a special cup intended for tobacco. The hole located in the upper part was closed with a horn, metal or wooden stopper, which could be pulled out at any time and this model could be used as a smoking pipe. The blade of the hatchet was decorated with engraving. The tomahawk had an elegant appearance and was often used as a gift to establish diplomatic relations between the Indians and European settlers. - Espontone type

. The chopping parts of these hatchets could have different shapes and sizes. The handles at the base were often decorated with decorative appendages. The blades were removable. If necessary, they could be removed and used as a knife. - Peak tomahawks

. These are products, the butt part of which was equipped with points and hooks. A similar form came from boarding axes. Peak tomahawks were widely used by settlers for household work. This option gained wide popularity among the Indians, who over time began to use it as a weapon.

- Hammer tomahawks

. These products, like tubular tomahawks, were widely used in trade. They were especially in demand among colonial shooters and Indians. But the difference between tomahawk-hammers and tubular versions was that the former had hammers in the butt part. Their design was not as ornate as the tubular ones, so they were not used as diplomatic gift items.

- Trade axe

. The product does not have an elegant shape. The butt, which has a rounded shape, was used as a hammer. The handles of these axes are inserted from below the eyelets, and in some models - from above. Since this version of the ax was primarily used by women, it was called the “tomahawk squaw.” The sizes of trade axes varied. Small dimensions were convenient for wearing behind a belt. Therefore, the products were also called “belt axe”, or “bag axe”. This item was used for trade between North America and Europe. In Indian villages, the trade ax was used as a household tool and as a military weapon. - Halberd-type tomahawk

. The hatchet consists of a chopping part and a long handle, at the end of which there is a long bayonet hammered into it. This model was made from a monolithic steel plate, mainly of a wide arcuate or semicircular shape. The butt was equipped with two additional points. Some models replace these flat points with metal spikes or semi-circles for tobacco. The head of a halberd hatchet can be dismountable and attached to the top of the product with a thread. Fastening the handles can also be done using threads, mainly in cases where the ax is made of wood. If the handle is metal, then it and the top can be one piece. Brass was also used to make handles. In such models of halberd axes, the tops were inserted into special sockets in the handle and secured with rivets.

Literature

- Kotenko Yu.

Indians of the Great Plains. - M.: Publishing House "Technology for Youth", 1997. - P. 105-109. — ISBN 5-88573-005-9. - Levin Bernard.

Knives catalog. - M.: AST, Astrel, 2007. - S. 342-345, 347, 348. - ISBN 978-5-17-056495-8, ISBN 978-5-271-22412-6, ISBN 0-87341-945 -6 (English). - Makivoy Harry K.

Throwing knives and tomahawks / Trans. English - M.: AST, Astrel, 2006. - P. 109-128. — ISBN 5-17-028733-X, ISBN 5-271-10877-5, ISBN 985-13-3200-3, ISBN 0-8048-1542-9 (English). - Morgan L. G.

League of Hodnosaunee, or Iroquois / Trans. from English - M.: Head. ed. Eastern literature publishing house "Science", 1983. - P. 189-191. — (Series “Ethnographic Library”). - Popenko V. N.

Edged weapons. Encyclopedic Dictionary. - M.: Boguchar, 1996. - 479 p. — P. 276, 279, 300, 302, 364, 372, 373, 375, 425, 427, 462-464. — ISBN S-88276-023X. (There are significant distortions in the illustrations and errors). - Stukalin Yu. V.

Encyclopedia of the military art of the Indians of the Wild West. - M.: Yauza, Eksmo, 2008. - P. 305-307. — ISBN 978-5-699-26209-0. - Trufanov I.P.

Kenai tomahawks from the ethnographic collection of I.G. Voznesensky // Collection of articles. MAE. - L.: “Science”, Leningrad branch, 1967. - T. XXIV. - pp. 85-92. - Mails, Thomas E.

The Mystic Warriors of the Plains: The Culture, Arts, Crafts and Religion of the Plains Indians: . — Second edition. - Tulsa, Oklahoma: Council Oak Books, 1991. - P. 471. - 618 p. — ISBN 9781571780027. — ISBN 1571780025.

Tactical weapons

The battle hatchets that American soldiers were equipped with have undergone major modifications in our time. Modern and more improved versions of tomahawks have appeared. Since these products were intended not only to perform combat missions, they began to be called tactical.

Tactical axes and tomahawks were in great demand among American soldiers during Operation Desert Storm. Without a compact and convenient device for breaking doors, the soldiers were forced to carry huge fire axes with them. Tactical hatchets are much lighter and more maneuverable, and besides their main task (cutting), they perform a number of additional functions. They can be used to knock down padlocks, open doors, break glass in cars, etc. In a combat situation, such an ax is considered indispensable, especially when it is undesirable to use firearms. Similar situations may arise if the battle is fought near flammable and explosive substances or toxic chemicals.

Tactical axes and tomahawks are especially popular in the special forces of the United States of America. These models did not take root in the army of the Soviet Union. The USSR military command initially planned to equip personnel with tactical hatchets, but over time they decided that this would be too expensive. An analogue of the American tomahawks in the Red Army was the sapper shovel, which, according to the Soviet leadership, was no worse.

The appearance of steel tomahawks among the Indians

The first metal axes were traded by settlers for furs. Having quickly learned to wield tomahawks, the natives surpassed their teachers in this art. The Indians learned the basics of using a tomahawk from British sailors who used axes in naval battles during boardings. Moreover, the Indians were able to master throwing techniques, forgotten in Europe since the times of the Franks, and even surpass the ancient Europeans. Throwing masters could throw several tomahawks in a couple of seconds. The Missouri type of ax was most suitable for throwing. The Spanish halberd-type ax was suitable only for close combat. The ax could be thrown at a distance of up to 20 meters.

Unlike the European battle axe, the tomahawk was not designed to penetrate armor, however, during the heyday of the Indian wars, armor was no longer worn. Due to its light weight and relatively short handle, the ax could deliver many quick slashing blows in battle with several opponents. Moreover, the design of the tomahawk allowed even a physically weak person to inflict deep, often fatal wounds.

Since tomahawks were well sold by local aborigines, manufacturers began to produce axes taking into account the preferences of specific tribes. It is worth noting that at first the axes were made of simple iron, and the eye was not pierced, but bent, followed by welding. Often such eyes burst at the most inopportune moment, especially in the cold.

To save space during transportation, the axes were not equipped with handles, which were made by the Indians with their own hands. When making the handle, it was decorated by the aborigines with truly barbaric luxury. Everything that was at hand was used for decoration, from leather and wire to human hair and even scalps. Without knowledge of metallurgy, the Indians could not independently modernize ax blades. Having learned this only at the beginning of the nineteenth century, they began to forge axes themselves, giving them a more convenient shape.

When many Indian tribes were exterminated and the remaining were driven into reservations, the art of using a tomahawk began to be forgotten until it practically disappeared.

Tomahawk in battle

Traditionally, the Indians, like many primitive tribes, used clubs with a ball-shaped end as striking weapons. It was thanks to the skills in handling these weapons that the European ax fell so easily into the hands of Indian warriors and turned into a formidable tomahawk. Already at the beginning of the 17th century, the idea that the tomahawk was the main weapon of savages was strengthened in the minds of the colonists. They feared him much more than bows and arrows. Wounds inflicted by an ax were in most cases fatal. Ethnologist Wayne Van Horn examined skeletons with signs of tomahawk damage and identified the most common areas of injury. It turned out that the wounds were most often on the skull, collarbone, forearm and ribs. This suggests that the most common method of attack was a slash to the head. The collarbone suffered if the blow was thrown casually or was not accurate. If the unfortunate person tried to protect himself from the blow with his hand, then the forearm received damage. To illustrate the use of a tomahawk in business, here is a story that happened to the family of the pastor of the Baptist Church, John Corbley. John lived with his wife and five children on a farm a mile from the fort. On Sunday, May 10, 1782, the whole family went to church, where the head of the family was supposed to read a sermon. The priest himself walked behind his family and thought about his speech for the parishioners. At that moment, the defenseless family was attacked by a detachment of Indians. The savages shot the pastor's wife and tomahawked his children. After committing atrocities, the savages disappeared. The father's grief was immeasurable. But fortunately, his two daughters were able to survive the scalping and recovered from their terrible wounds. Today, a memorial sign has been erected at the site of that monstrous massacre. It's hard to read about such events, but they help us feel that the tomahawk is not an abstract symbol or literary device, but a real weapon - a tool for killing. Even after the Indians were able to obtain a significant number of firearms, the tomahawk did not lose its importance. Immediately after the shot, the gun turned into a long club, not very convenient for combat. At this moment there was a need for edged weapons. This niche was occupied by the tomahawk. In addition, the ax was much better suited for raids and surprise attacks, since the gun, with the roar of a shot, warned of the danger of people a mile around. The ax made it possible to shoot sentries and patrolmen almost silently. Despite the popular misconception, tomahawks were almost never thrown. Throwing an ax effectively even at a stationary object is not easy. You need to estimate the distance to the target and understand how many times the ax should turn over in the air. And throwing an ax at a moving target is not a rewarding task at all. Such use of an ax in battle was unwise not only because of the high probability of missing, but also because it left the thrower without a weapon. Thus, the reason for the stunning success of the tomahawk was the sum of a number of factors. Relative cheapness - getting the required amount of skins to buy an ax was not difficult for the Indians who lived by hunting. It was more difficult to find a merchant. Sometimes it took weeks to get to the trading post. Remarkable qualities as a tool: hollowing out boats, building houses, collecting firewood and many smaller everyday tasks in forested areas were accomplished more easily and quickly using an iron axe. Finally, the similarity in handling the usual clubs, thanks to which in battle a warrior with a tomahawk could use techniques that had already been mastered earlier on wooden clubs. Tomahawks were so effective in the hands of the natives that the ax replaced the saber in some reconnaissance formations of the colonial powers in North America. It seems incredible, but even now, in the 21st century, tomahawks are in service with the American army. And these are not missiles, but tactical tomahawks - descendants of those same Indian battle axes.

Magazine: Forbidden History No. 26(93), December 2020 Category: History of the New World Author: Vladimir Antonov

Tags: Indians, America, weapons, steel, corkscrew, tool, Forbidden History, tomahawk

- Back

- Forward

Disadvantages of modern models

Modern industry produces many types of tomahawks for every taste. From the frankly predatory SOG m48, to the quite peaceful-looking Jenny Wren Spike, advertised as women's. In general, modern tomahawks can be divided into three groups:

- Identical. Such axes are produced only by Cold steel. They are a forged hatchet on a wooden handle, put on using the reverse insertion method;

- Tomahawks attached to a plastic handle. This is the notorious SOG m48 and similar models;

- Tomahawks, cut from a single piece of metal, with pads in the handle area.

Modern tomahawk with plastic handle

Tomahawk made from a single piece of metal

Let's take a closer look at the advantages and disadvantages of each type.

The identical tomahawks are a classic ax design that has remained unchanged for hundreds of years. Usually they are made independently or ordered from blacksmiths. Despite their inconspicuous appearance, they are a formidable weapon, proven in many battles over the centuries. They are distinguished by a simple design, perfect balancing, the ability to adjust the handle specifically to your hand, and ease of repair. The ax itself is “indestructible”, and the handle is easy to make with your own hands.

Tomahawks on a plastic handle have a very menacing appearance. Thanks to their light weight, they can be used at high speed. The butt is often made in the form of a pecker, a hammer, or even a second blade. During operation, these axes revealed many shortcomings. The round handle often rotates in the hand when striking, which is why the blow turns out to be sliding. It is absolutely not suitable for throwing, despite the assurances of the sellers (the handle breaks after several hits against a tree). Practically unsuitable for household work. This type of tomahawk is better suited for intimidation than for serious work.

One-piece tomahawks can be called an ax with great stretch. Rather, these are blades shaped like an ax. Due to the design features and low weight of the working part, they are not capable of performing the role of a powerful piercing weapon. It rubs your hand a lot when using it. Their only advantage is their solid structure, which is very difficult to break.

Tomahawks in modern times[edit]

Modern tomahawk.

American soldiers have taken tomahawks with them to numerous modern wars. So, during the Vietnam War, they had a popular “Vietnamese tomahawk”, developed by Peter LaGan. Currently, countless modifications of these axes (including the “Vietnamese” one) are produced by Western companies. Many modern models of axes with this name are designed for military use (and are used). In everyday life, tomahawks are used in sports and historical reconstructions.

The famous American cruise missile also received the name “Tomahawk”.

History of the name[edit | edit code]

The name “tomahawk” for metal hatchets was first published in his dictionary by the famous colonist and explorer from Virginia, John Smith.

but he took it, somewhat distorted, from the language of the local Algonquin Indians - Powhatans.[2]

In all the Algonquian languages of eastern North America, variants of this word were used to name a variety of war clubs, clubs and axes. Thus, the Englishman William Wood, in a book published in 1634, wrote: “Tamahawks are sticks two and a half feet long with a large knob like a football.”[3] In many other Indian languages, also related to different language families had their own names for different types of weapons, including hatchets of European origin. For example, among the Seneca Iroquois, the word " o-sque'-sont

" originally referred to cross-grooved stone axes. It also transferred to metal hatchets[4][5].

Traditional Indian terms[edit | edit code]

- Algonquian languages: Proto-Algonquian root temah-

- “to cut off”, Powhatan -

tamahaac

[6];

Delawares - tëmahikàn (-ni)

,

təmahikan

, where

təmə-

“cut off” and

-hikan

is a suffix meaning “tool”[7], Malese and Passamaquoddy -

tomhikon

, Abenaki -

demahigan

. - Iroquois languages: Seneca - o-sque'-sont

;

onaida - atkulé·ki

[8];

Tuscarora - no-Kuh

(axe)[9];

Cherokee - ( galuysdi

, axe)[10]. - Siouan languages: Santi Dakota - oŋspecaŋnoŋpa

[11].

The benefits of artisanal production. What's better than a forged tomahawk?

It is not difficult to make an ax with your own hands. The product will turn out to be of truly high quality, as a classic ax should be, only if it is produced in a forge. In it you can forge both a standard ax, necessary for carpentry work, and a very aesthetic, exclusive tomahawk.

It can be used as a gift, souvenir or interior decoration. In terms of their technical characteristics, forged products are much better than factory cast ones. This is due to the characteristics of the crystal lattice of metals, the structure of which can be changed during forging. As a result, a tomahawk hand-made in a forge with changes in the crystal structure can withstand force and shock loads well, and the blade of such a tomahawk remains sharp for a long time. The service life of hand-forged axes is much longer than that of factory-made axes.

The first steel hatchets

The British, whose settlement was located side by side with Indian tribes, were the first to see the tomahawk. The ax was used by the Indians for hunting and in close combat. The Europeans suggested that this tool would be more effective if it were made of steel rather than stone. Thanks to the British, the first iron hatchets were brought to the American continent, which later became the most popular product.

The tomahawk ax improved by Europeans began to be in great demand among the Native Americans. The Europeans exchanged it for furs mined by the Indians. The production of these axes was put on stream.

Over time, they created a certain technology that can significantly speed up and reduce the cost of the production process. It consisted in the fact that tomahawks were made from an iron strip twisted around a steel bar, the ends of which were subsequently welded to each other, forming a blade. But there was also a more expensive option - craftsmen clamped a hardened steel plate between the welded ends of the steel strip. In such axes, it was a blade and performed a cutting and chopping function.

Products were mass-produced in Europe, mainly in France and England, and delivered to local aborigines. Previously, this tool was used mainly for household needs and, in rare cases, for hunting. After modernization, the tomahawk Indian battle ax became a formidable weapon used by the British Marines.

5 More Formidable Battle Axes

Last time we talked about the five most famous battle axes of bygone eras. Of course, the variety of types of this wonderful weapon does not end there. Today we will talk about several more of the most interesting types of battle axes and demonstrate why over time they have literally become a universal method of fighting in close combat.

Tomahawk

The tomahawk is a North American Indian battle axe. Initially, tomahawks (English transliteration of the original dialect of the Indians) were called various clubs and clubs, the favorite weapons of the aborigines. Afterwards this name was transferred to metal axes, but some language groups also retained their own designations for these weapons.

Tomahawks are very diverse. The “boat” tomahawk is characterized by a butt with a cup for smoking mixtures, while the “esponton” tomahawk has a blade perpendicular to the handle. In addition, a small hammer or an additional point could be attached to the butt. Often the pommel was decorated with a pointed horn or spike - the result was a miniature halberd.

Thanks to the media, many believe that the tomahawk is an exclusively throwing weapon, and that the Indians threw them in one gulp, like the Roman legionaries threw their pilums. History and common sense say the opposite: a tomahawk is a melee weapon, and although throwing it is convenient, a warrior will take such a step only in case of emergency.

Weapon

Musvalk: a knife made from spaceship materials

Franziska

Francis, as you might guess from the name, was the battle ax of the Franks and other Germanic tribes. It became most widespread among the Merovingian Franks in the 5th-6th centuries. Two varieties of Francis are known: for close combat and for throwing.

An ax for close combat was mounted on a long (a meter or more) ax handle, which made it possible to take it with both a one-handed and two-handed grip, which is very important for an ax. The ax of throwing Francises was shorter than the length of a warrior's arm, but still noticeably longer than that of other throwing axes.

Lochaberakst

The Lochaber ax got its name in honor of the locality of Lochaber, in Scotland. A long infantry ax resembles a reed: a one and a half meter shaft is crowned with a long (up to 50 cm), smooth blade, more like a halberd rather than an ax. Often the edge of the blade was wavy: like the flamberges, this gave the weapon excellent cutting properties and made it possible to literally saw through the thinnest areas of armor.

Considering the abundance of heavily armored combat units in the armies of the 14th-16th centuries, the popularity of the lohaberakst is quite understandable. A hook was often attached to the butt, which could be used to pull riders out of their saddles and pull infantrymen out of tight formation. Such versatility made the weapon indispensable: there is an opinion that the halberd appeared precisely as an evolution of the Lochaber ax.

Halberd

In fact, the halberd is no longer a classic battle ax, but an independent subtype of polearm bladed weapon. It is characterized primarily by a combined warhead: in addition to the chopping edge of the axe, the top of the halberd was decorated with a long faceted tip of a spear point, and the butt was equipped with a hook or counterweight spike. The long (1.5-2.3 meters) shaft made the halberd an excellent weapon against cavalry: a detachment bristling with halberds could stop even heavily armored cavalry at full gallop.

As in the case of the lochaberax, what made the halberd popular is its versatility: with this weapon you can stab, chop, and cut the enemy, while maintaining an impressive distance between him and you. The handle, protected with steel strips, protected the shaft from being cut, but even without these precautions it is very difficult to cut a long, smooth pole. There was also a boarding modification of the halberd: it was equipped with a large hook and an even longer (up to 3 meters) shaft.

Glaive

A glaive, also known as a glaive, is another type of pole weapon, which is a cross between a spear and an axe. It consists of a one and a half meter shaft and a tip in the shape of a narrow, elongated crescent, the length of which reaches 40-60 cm. A distinctive feature of the glaive is the “sharp finger,” which is a sharp tip of the butt, directed perpendicularly or at a slight angle to the blade. With its help, you could grab the enemy’s weapon or try to pierce him yourself.

Tomahawk decorations

Many Indian tomahawks were made quite simply and not all of them were additionally decorated. Less often, compared to tube ones, they received rich decoration and. The usual decorations include relief details on the sleeve and tube, figured holes on the canvas and engraving. The holes are round, heart-shaped or triangular. The latter could be either small or occupy most of the canvas. Rarely, the canvas is cut with a complex openwork hole. The engraving was not only ornamental, but also with European heraldic motifs, sometimes with a plot. This design is made in the style of pictography and primitive drawings of forest Indians. Paintings in the style of the Plains Indians are very rare. A rare decoration are large round convex brass bosses on the sides of the canvas.

There are often inscriptions: political slogans or, more often, some signatures of the manufacturer or owner. Or dedicatory inscriptions, like the tomahawks presented to the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. In one of them it was simply engraved on iron. The other has an inscription on a silver insert on the handle. Another one has a name engraved on a horizontal gold strip inlaid into the canvas. The next one has an iron engraving that conveys the name in a rather unusual way, and the vertical silver stripe on the other side of the canvas is too worn out. Tomahawks intended as gifts for leaders had gold and silver inlay on the striker. Moreover, the figures of the inlays could be very different.

Common decorations for Indian tomahawks were covering the handle with fur or cloth, stuffing brass nails with large heads, or wrapping it entirely with dense turns of brass or copper wire or strips woven from porcupine quills. Some tomahawks have handles finished in exactly the same way as gun stocks in the 18th-19th centuries. — they have dark transverse stripes applied with aqua fortis

, that is, nitric acid. Apparently, imitating this technique, they used firing. Less commonly, the handles were painted, for example, alternating red, green and black rings. There is even Chinese lacquer painting. Some of the handles were carved (the Apache leader Geronimo made one for himself). Often the front side of the handle was covered with jagged finger cutouts. Sometimes feathers, ermine skins and scalps served as decoration. Dance-ceremonial tomahawks had various pendants at the end of the handle in the form of beaded leather triangles with fringe, bells, and stripes of cloth or fur. Round mirrors could be sewn onto the latter. The plug that closes the top of the channel in the handle of a pipe tomahawk can sometimes protrude about ten centimeters and have several strands of scalp fringe at the end. Richly decorated pipe tomahawks had handles trimmed with inlays of tin, brass, nickel silver, or even silver. Images could be engraved on these inserts. For example, the figure of an Indian, and on the mouthpiece - the head of a fish. A silver mouthpiece also has a cap on a chain that closes it. Or a silver chain simply connected an open silver mouthpiece to a similar insert higher up. This is the symbolic “silver chain of friendship”. The mouthpiece and the protruding upper end of the handle could also be inlaid with lead. The spirals of the lateral processes on esponton tomahawks were also filled with soft metal.

Types of tomahawks[edit | edit code]

Earless tomahawks[edit | edit code]

Celts[edit | edit code]

The earliest "tomahawks" of the Indians with metal blades (English celtiform or celt form tomahawks

) repeat the design of local ancient stone and copper wedge-shaped axes[13], which do not have holes for the attachment. Their iron blades were also inserted (hammered) with a sharpened butt into the handle. Iron is of European origin. Time of existence - approximately mid. XVI century - beginning XVII century

Pointed Celts[edit | edit code]

If the celt has the shape of a narrow elongated triangle, then its sharp butt goes right through the handle, forming a point at the back. Flat iron hatchets with graceful outlines and a wider point on the butt were supplied by the Spaniards. They were intended to be inserted into a split handle. They have recesses at the top and bottom of the canvas, ensuring reliable fixation on the handle with a binding. The celt canvas may have a longitudinal convex rib for strengthening. Later, the Hudson's Bay Trading Company produced similar axes from bronze. Their canvas is in the shape of a simple wide triangle and is reinforced with elements of rigidity. There are also recesses at the top and bottom for fixing on the handle. The 18th-century celt can be forged into a clip with a pin at the bottom, which is designed to be inserted into a wooden handle, which brings them closer to the halberd tomahawks of the same period.

Even at the end of the 19th century. Among the Indians, celt tomahawks are found: in the form of a hatchet with a protruding sharp edge or a blade driven into the handle (espontone type), made from various scrap metals.

Ear tomahawks[edit | edit code]

Missouri war axes[edit | edit code]

In the Missouri River region, French-Canadian-supplied Missoruri War Ax style tomahawks were popular among nine or more tribes from the early to mid-19th century. The term itself was introduced by collectors of Indian weapons. The axes had a simple butt with a round eye with a diameter of 1 inch (2.54 cm) and a thin but rather large blade 4-6 inches wide (10.16-15.24 cm), the neck near the butt was no more than 1 inch, length - 7-9 inches (17.78-22.86 cm) (possibly sometimes more). The handle in the early period was rarely more than 14 inches (35.56 cm) long, in later examples it was longer. Weight about 1 lb (454 g). The blade usually had no marks of sharpening, it was just a straight cut sheet of iron. There was no hardening. The surface of the canvas can be decorated with engraving, round or shaped slits, for example, in the shape of a heart, sun, crescent, or bear's paw. Rarely, the neck of the canvas and the spine were decorated in relief. The features of these tomahawks indicate that they could only be used as weapons, either combat or ceremonial.

Pipe tomahawks[edit | edit code]

This was the most popular type of tomahawk. It appeared around 1685 and became widespread from the middle of the 18th century among the eastern tribes. The production of pipe tomahawks was carried out by the British, French and then Americans. Pipe tomahawks had a through channel along the entire length in the handle, and a cup for tobacco on the butt [14].

the neck could be made from a shotgun barrel, and in the later period - from a brass cartridge case. A channel was either burned into the soft core of the ash tree, or they resorted to gluing the handle from two halves. The mouthpiece was often made of wood in different ways, and if the handle was inlaid with metal, it was made of the same metal: tin, lead, silver. On later tomahawks it could be made of nickel-plated brass. The upper hole of the channel was closed with a round plug made of wood, metal, or horn. If it was necessary to clean the canal, it could be removed. A pipe tomahawk may have a broken blade, in which case it is simply used as a pipe.

Some tube tomahawks can be converted into a hammer or point tomahawk. In a rare variant, for this purpose the head of a hammer is screwed into the cup of the tube, which has an internal thread. But usually the cup is unscrewed, and a spike is screwed in its place.

It is important that pipe tomahawks, unlike “sacred pipes,” did not have a sacred meaning, although among the eastern tribes they could be used in ceremonies with incense. Richly decorated pipe tomahawks - with engraving and inlay with non-ferrous metal on the canvas and metal parts on the handle - were also used in diplomacy between whites and Indians as gifts, because they represented a vivid symbol associated with the cultural traditions of the North American Indians: on the one hand there is, as it were, a symbol of peace, on the other - an “axe of war”.

A small number of pipe tomahawks from the Great Lakes region have a peculiar decoration in the form of a spike extending forward and down from under the underside of the blade with a small ring at the end or with the end wrapped in a ring. Its purpose is unclear, but this design resembles a trap for a bladed weapon. Pipe tomahawks also include large tomahawks with a handle 60 cm long, which in size are analogous to Missouri military axes. They were even popular among the same tribes.

Esponton tomahawks[edit | edit code]

“Espontoon tomahawk” (English: spontoon tomahawk) comes from a polearm with the same name that was armed with officers of the European armies of the 18th century - the espontoon. But it is even closer to the earlier protazan. There were other names for this type: “ minnewaukan

"[15] (with a deltoid[16] blade shape and without additional processes), "dagger-bladed", "diamond-bladed", and "French type" french type).

The blades of these tomahawks come in various sizes and shapes, for example, in the shape of a diamond or a large spiked arrowhead, and at the base they often have a pair of decorative spiral processes twisted in one direction or another. Rarely, these extensions were straight or slightly curved, angled forward, reminiscent of bladed weapon traps. There are paired processes. Sometimes they bend into rings, and in later versions they often form solid rings, or even simply turn into a pair of semicircles. The cloth of the tomahawk could be stylized to resemble a buffalo's head from the front. Short shoots form horns, and four holes on the canvas form eyes and nostrils. Another version of the tomahawk, which also has a blade in the form of a buffalo’s head, is distinguished by a blade that is “chopped off” at the front. Sometimes the blade of an espontone tomahawk in the shape of a diamond may have a large rhombic hole in the blade of the same shape (this was also practiced for ordinary tomahawks). A rare form occurs when the tip of the tomahawk has a significant downward bend. The existing copy of the tomahawk, which most accurately copies the shape of the protazan, dates back to the end of the 19th century, and not to the main period of existence of this weapon.

Tomahawks of this type were also sometimes made of brass. Often esponton tomahawks were tube-shaped and extremely rarely had a point or a second, smaller blade-shaped blade on the butt.

There were also earless tomahawks of this type, similar to the older Celts. A rare type is the tubular espontone tomahawk, which is equipped not with a flat blade, but with a pick-axe-type point, like a tomahawk with a point.

Similar blades were also used for batons. But the latter were often also equipped - just like Indian knives (type “beaver tail”, French dague, dag, daggy) and spears - with a replica of the Confederate army spear (the so-called “bayonet”) with a pair or four rectangular protrusions in basis.

From the beginning of the 18th century, these tomahawks were supplied by the French to their controlled territories - right up to the mouth of the Missouri. Then their production was picked up by the British, Americans, and Canadians.

Pointed tomahawks[edit | edit code]

Tomahawks with a point or a hook on the butt (peak tomahawks) (eng. spike ax or spike tomahawk

[17]) are so-called

boarding axes

, used in the navy, or workman's (carpenter's) axes.

Both of these categories of axes were often equipped with the specified device, which was used when storming an enemy ship or as a hook during various works. The shapes and sizes of these tomahawks are quite varied. The surviving examples of them may be actual boarding axes, working axes, or also specially made as weapons for sale to the Indians. The points were more often in the form of thin spikes, less often - in the form of flat blades or thick short or longer beaks. Since the presence of a point on the butt is not always convenient, there are rare specimens with the point bent into a ring[18]. The handles are often reinforced with iron triggers, which can be either integral with the head or separate. In the boarding version, the blade often has a pair of jagged notches on the underside. Less often, the shape of the blade itself is such that the notches are directed towards the handle.

Conventionally, a couple of single samples can be classified as this type of tomahawk. One of them has on the butt not a spike, but a kind of decoration ending in a small rod with a cap, which could not serve as a hammer. The second has a hook on the butt in the shape of a bird's head.

Pointed tomahawks were especially popular in the eastern forests, and in later times, for example, the Iroquois could pose for photographs with a fire ax.

Tomahawks with a hammer[edit | edit code]

Externally, tomahawks with a hammer on the butt or hammer poll tomahawks differ little from pipe ones. Unless they're much less elegant trade axes

with a hammer.

Used by Indians and settlers, they were apparently popular with colonial marksmen as belt axes

.

Trade axes[edit | edit code]

Trade axes (English: trade axes) are so named because of their use in the fur trade (other goods were also called this way), hence the following name - fur trade axes

(English: trade fur axe). They were supplied for trade with the Indians of Holland, France, England and the settlers of North America itself. The Indians used them not only for economic purposes, but also for war.

These axes are less elegant than the tomahawks themselves. Their butt is often simply rounded or flat (to be used as a hammer). Many trade axes, based on the shape of the blade, are classified as half-axes

.

Some axes were intended to supply the army, where they were used from the Revolutionary War through much of the 19th century as a hand

axe. Some of them were smaller versions of the usual work axes and felling axes of lumberjacks. Others featured a hammer boss on the butt and a nailer slot on the underside of the blade. These are of the same type as a roofer's hammer or roofing axe. A similar half-axe belongs to the lathing hatchet. The hammer on their butt has such a small diameter that it can be considered a blunt spike. Despite their original purpose, these axes could be decorated with inlays of other metal and inscriptions. A number of axes are double-sided, that is, with identical blades directed in different directions, like labryses. The handles were inserted either from above the eyelet or from below. The holes were of any kind: from round to those shaped like elongated narrow triangles.

They were called differently: “tomahawk”, “trade axe”, “hatchet”, “Indian axe”, “squaw axe” or “tomahawk-squaw”. The latter names are due to the fact that women often worked with these axes, which also applies to large working axes. The same name was given to ordinary tomahawks that had a rounded butt. The names “belt axe” and “bag axe” are given to the smallest specimens for the way they are carried. These include double-sided butterfly belt axes

(eng. butterfly belt axes).

Halberd tomahawks[edit | edit code]

Halberd tomahawks (English halberd tomahawks, trade halberds) or otherwise “battle axes” (English battle axe) are specially made hatchets resembling halberds, intended for trade with the Indians. Their origin is English.

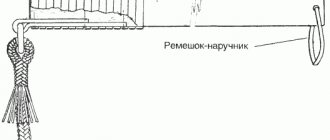

The handle of such tomahawks is usually attached using a conical sleeve, like a spear, but there are also examples with a long rod that is driven into the handle. inlet at the lower end of the wooden handle

in the form of a sharp cone. The iron part is monolithic and most often represents a semicircular or other shaped wide (rarely narrow) hatchet with two additional flat points - at the top and on the butt. Other varieties have a smoking pipe cup or a hook-curved spike on the butt. In one rare species, the calyx of the tube is located directly under the butt point. The upper point is not always present. The points can also have the shape of a chisel. Some models have a collapsible head. In this case, the head is screwed onto the vertical part (sleeve with a point) along the thread. The tip and cup of the smoking pipe can also be threaded.

Some halberd tomahawks do not have a sleeve for the handle. Their handles are iron and form a single unit with the head. Less commonly, an iron or brass handle was inserted into a socket and secured with a rivet. These handles are round or flat and have a pointed end. Outwardly, such a weapon resembles a medieval European throwing hatchet - a herbat. Others had grooves on the handles for wooden plates with holes for rivets. Typically, these axes are quite light, as they are forged from fairly thin metal.

Ordinary eared tomahawks, in which the tip of a spear is inserted into the eye, are sometimes classified as halberds. Sometimes it is replaced by a bison horn.

It is believed that the not very convenient halberd tomahawks were, rather, a sign of the status of the leaders. They were used by the Eastern Woodland Indians in the 1700s until the end of the Revolutionary War. Over time, a certain number of these tomahawks reached the plains, ending up, for example, with the Apaches.

Other "tomahawks"[edit | edit code]

In literature, the name “tomahawk” is occasionally used for other Indian weapons. Including for Athapascan clubs, which were a sawn-off reindeer antler with a protruding appendage into which a small stone or iron point, like an arrowhead, was inserted. The insert could have been of a different shape. Iron inserts could also be driven in along the handle.[19] Similar weapons were also noted among the Indians of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia. The American Eskimos also had it ( pogamagan

,

bastard

)[20][21].

The Indians made smoking pipes, the heads of which sometimes more or less accurately conveyed the shape of a pipe tomahawk, usually in the form of a hatchet and rarely in the form of an espontone. Catlinite stone was often used for this. Tin inlay was used. Less commonly, such a tube could have a separate catlinite handle-chubuk. If it is long enough, it was assembled from several sections. Catlinite tubes often did not completely imitate real tomahawks or were completely conventional. Products made from other types of stone (sandstone, black slate) completely repeated their design. The pipe tomahawk style could also be carved entirely from wood (Iroquois).

In Herman Melville's novel Moby Dick, "tomahawk" refers to a correspondingly shaped smoking pipe belonging to one of the characters, Queequeg.

Revival of the tomahawk in the 20th and 21st centuries

Peter LaGana, a descendant of the Mohawk Indians, was the first to use the tomahawk. A WWII veteran, Marine and hand-to-hand combat instructor came up with the idea of creating a special military tomahawk for the US Army. Having created a perfectly balanced model with the help of children and women who, without any skills, were able to work and throw a tomahawk quite effectively, Peter began to actively advertise his development. After conducting a series of spectacular tests, LaGana opened his own in 1966, which fired about 4,000 tomahawks. Almost all of them were purchased by Marines who participated in the Vietnam War. In this conflict, the tomahawk proved to be an excellent short-range melee weapon, securing the name “Vietnamese axe.”

However, Peter's plans to introduce the tomahawk into the standard equipment of the Marines were not destined to come true. After the Vietnam conflict, the tomahawk's popularity declined and the company closed in 1970.

A new surge in the popularity of tomahawks occurred in the 2000s, in connection with the military operations of the US Army in the east. It was perfect for opening doors. Nowadays, so-called “tactical” tomahawks are produced by many companies and everyone can choose an ax based on their needs.

Tomahawk axe: history, origin of the name, types and characteristics

It is believed that the word "tomahawk", which gave the ax its name, came from a mispronunciation of the Indian word "tamahakan" - a cutting object.

In pre-Columbian America, the Indians used this word to describe something like “a stone with an elongated shape, sharpened on both edges and mounted on a wooden handle.” And this device didn’t look at all like how it all looks in movies about Indians. It was only with the discovery of America that the word “tomahawk” began to refer to metal axes.

Characteristics and Similarities of Tomahawks

Ax blades have many shapes that roughly resemble a wide variety of axes from different eras or spearheads that lie perpendicular to the shafts. Butts also have several shapes that resemble other axes, such as peckers. Some butts were in the form of hammers or hammers with pins, square and round sections.

However, there was also an ax in the form of a small halberd. Due to its functionality, the ax was used in battle, hunting, and also in everyday life - it was used to cut down trees. The Indians needed this ax only for close combat; they threw it at enemies extremely rarely.

Axes were thrown mainly as sports equipment during training. The functionality of battle axes made it possible to remove the blades from the shafts and use them as a knife. Such axes weighed within half a kilogram, the length of the cutting edges of the blades was up to 100 mm, and the length of the straight shafts was within half a meter.

The emergence of tomahawks

Due to the fact that the manufacture of metal axes was inaccessible to the Indians, they exchanged them from the “pale-faced” who appeared in that area at the beginning of the 17th century. Thus, the first tomahawks were steel and improved battle axes of the British Marines, used for boarding ships.

Spanish tomahawks were different from English ones. They had wide, moon-shaped, rounded blades. The French living in Canada were the first to make tomahawks in the form of klevets.

Tomahawks - a formidable weapon of the Indians

By exchanging provisions for axes, the Indians turned them into even more formidable weapons. They also learned the technique of using axes and significantly outperformed their teachers, especially in close combat. In throwing, they themselves became unsurpassed masters - all the axes they threw always hit the target from a distance of up to 20 meters.

The functionality of the axes allowed even weak people to use them thanks to the lever handles. The characteristics of tomahawks made it possible to operate both in the thick of battles and in one-on-one combat. In addition, wounded animals were killed with axes.

The first tomahawks

Based on the finds, the first Indian axes can be dated back to the 16th-17th centuries. Axes with metal blades were similar to ancient stone and copper wedge-shaped axes, without holes for the shafts.

The metal parts of the blades were hammered or inserted with pointed ends into the shafts. Since such axes were called earless, they belong to the Celtic group.

Peace Tubes

Perhaps as the most common type of ax, we can talk about pipe tomahawks. Through channels were made in the shafts of the axes, and the upper parts of the shafts at the holes were plugged with round plugs made of wood, deer antlers, or even metals. Containers for tobacco were placed on the blades on the butt side. The result was an ax-pipe for smoking.

In addition, there were pipe tomahawks, which had sacred meaning. Specifically: “sacred pipes” or “peace pipes.” Special rituals were carried out with the participation of leaders and elders; ax pipes were lit in a circle, symbolizing reconciliation or the end of wars.

Pipe tomahawk

The “palefaces,” who respected local traditions, often used pipe axes. They were richly decorated as gifts to the leaders. The blades were engraved and the shafts were decorated with a wide variety of metal details.

Missouri tomahawks

Until the 19th century, some of the most sought-after battle axes were “Missouri.” They got their name from the local Missouri River. A characteristic feature of such axes was the presence of a large blade, which turned into a simple butt with a round eye.

This served as the name for lug tomahawks. The presence of large surfaces of the blades made it possible to make shaped holes for a more attractive appearance. The supply of such axes was carried out by the French living in Canada. Their cheap production made it possible not to harden the blades, because these were battle axes.

Espontone battle axes

From English “spontoon tomahawks” is translated as espontoon tomahawks. A wide variety of configurations and sizes of battle axes had characteristic twisted appendages at the base of the blades. In the European army, only sergeants could possess such weapons.

The tomahawk shafts did not wedge. Thanks to this, the metal parts of the ax blades could be removed from the shafts and used as combat knives. In addition, such blades were often attached to war clubs that were used by the Indians.

In most cases, cavities were made in esponton tomahawks, like in tubular axes. Sometimes one came across a number of earless espontone axes, similar to the ancient axes of the Celts.

Trade tomahawks

Trade tomahawks are the simplest and cheapest ax of all the tomahawks. They are characterized by the fact that the blades, turning into simple butts, were flat or rounded and were used as hammers.

There were also types of axes whose blades were double-sided. The shafts were inserted both above and below the holes, based on the types and shapes of the axes. Due to their shape, they were called “half-axes”, since they were very small in size.

The Indians used these mini-axes mainly for agricultural work, although also for war. Such axes were supplied by the manufacturing countries themselves: England, France, and Holland.

Halberd-type tomahawks

From English “halberd tomahawks” is translated as halberd tomahawks. These are exact copies of halberds, but with short handles. Mainly used in trade with the natives. The shafts were secured using cone-shaped bushings. This method of fastening was borrowed from copies.

At the ends of the ax shafts there were metal bayonets shaped like a sharp cone. The metal parts of the blades were solid, there were no slots. The shape of the blades was wide and semicircular on one side. While the other side and the top resembled a flat point.

Halberd tomahawks were in the “assortment”. Some had no points on top, and some had chisel-shaped points. In some, the points were replaced by curved hooks, spikes or smoking cups.

There were models with collapsible heads that could be screwed onto vertical bushings with threaded points. In addition, each of the points could be attached, of course, if there was a cut thread. There were also tomahawks that did not have bushings for the shafts, since they were entirely metal.

Halberd Tomahawk

Later, tomahawks with shafts made of brass and other metals appeared. They were inserted into sockets and riveted using rivets. Such shafts had a wide variety of shapes. They were flat, round, pointed at the ends.

Despite the fact that these products were not convenient for use in battle, the Indians used such axes to demonstrate their belonging to the leaders, because the presence of such axes was a sign indicating the status of the leader.

Main types of tomahawks

There were also battle axes-tomahawks, with hammers on the butts, or tomahawk-hammers, very similar to pipe axes, but not as elaborate as trade axes with hammers on the butts. Such axes were used not only by the Indians, but also by North American settlers, as well as colonist riflemen, who used them as belt axes.

Axes with points or hooks on the butt side are peak tomahawks, similar to boarding axes. Athapascan clubs can also be classified as tomahawks. These were products made from deer antlers with protruding branches into which points were inserted from whatever was at hand.

Indian woman with tomahawk

Tomahawks of our days

Despite the fact that almost 200 years have passed, tomahawks are still relevant today due to their functionality. Mainly attention was paid to them before the Vietnam War.

Peter Lagano, a well-known Indian at that time who served in the American army, managed to develop a peak tomahawk battle ax that could be thrown quite well.

Currently, the tomahawk ax can be used in tourism and in some sports, but most often it can be seen as a historical reconstruction.

About the nature of the damage caused by the Indian ax

Excavations studied by archaeologists in the territories of Indian settlements indicate that the skull, collarbone, ribs and left forearm bone are most susceptible to injury from tomahawks. Based on the nature of the damage to the skull of the examined corpses of soldiers who died from a tomahawk, it was believed that the blows with an ax were applied from top to bottom along an arcuate trajectory. Damage to the collarbone was apparently caused in cases where a slashing blow to the head did not reach its target. Injuries to the left or right forearm were less common. In all likelihood, they could have been produced while the person was covering his head. The second technique used by warriors of that time was an arcing slash to the body. It was applied along a horizontal trajectory. In such cases, the ribs were damaged.

Tomahawk: why the Indians did not abandon the battle ax after acquiring firearms

Perhaps most of us know what a tomahawk is. In our minds, a battle hatchet with feathers or a pipe is not just a formidable weapon of the Indians, but also, in fact, an obligatory attribute of their image.

However, not everyone knows about the true history of the tomahawk and the features of its use...

The history of battle axes of the indigenous people of North America dates back to the very first so-called “technological era” - the Stone Age. It was then, or rather during the Upper Paleolithic period, that is, about forty thousand years ago, that the first tools appeared, which became the ancestors of both the Indian tomahawk and modern axes. These products were sharpened stones that were attached to a wooden ax handle by tying or inserting into a groove. In particular, similar tools are found on the North American continent.

When the Stone Age was sent to the periphery of history with the advent of metal smelting technologies, weapons were almost the first to be reoriented to a new, stronger and more durable material. In Europe, Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, they were quickly able to not only tame more finicky steel, but also create more sophisticated types of bladed weapons - knives, daggers and swords.

And only in North America the technical revolution did not occur, largely due to its remoteness from other continents. Of course, smelting and processing of metals also appeared in the arsenal of skills of the ancient Indians over time, but these technologies were mainly used in relation to softer copper and gold, and the purpose of this work was to make jewelry and attributes for sacred rituals. Of course, this trend did not affect the development of weapons in any way - the only materials for their manufacture were wood and stone.

It was stone battle axes on wooden handles that were seen by the first European colonists who arrived in North America. Thus, the English naturalist Mark Catesby in his memoirs captured the following characteristics of the weapons of the Indians: “These were small stone hatchets. To make them, the workpiece was ground, sharpened to a sharp blade and attached to a wooden axe. They could be used as a weapon in battle or as a tool: for hollowing out boats and other household tasks. Stone tomahawks were the Indians' companions in everyday work and on military campaigns. With the spread of iron axes, stone axes fell out of use forever.”

The etymology of the word “tomahawk” itself is also interesting. In fact, in our usual sound, the name of the weapon of the indigenous people of North America owes its appearance to the Europeans, and not to the Indians themselves. The reason lay in translation difficulties. Colonists who were poorly versed in local languages and dialects simply incorrectly wrote down the Indian word “tamahak” (also “tamahakan”), which was in the lexicon of the Algonquian group of languages and meant “tool for cutting.”

The familiar “tomahawk”, according to popular belief, was first used by the legendary colonist Captain John Smith in a short dictionary of Indian words he compiled. He also pointed out that this term can denote not only a battle ax of a certain type, but also its other types.

After John Smith, the tendency to expand the scope of the use of the term “tomahawk” in relation to weapons only intensified. This word began to be used to describe almost half of everything the Indians fought with. Thus, the British colonist William Wood in his book “New England's prospect” (1634) noted: “A tomahawk was a club two and a half feet long (75 cm), with a spherical top.” Essentially, he was referring to the Indian war club made of wood, which was extremely popular. For example, people liked to “shake” it as an argument in a dispute, and it was also widely used during hunting.

At some point, almost every club or hatchet that was seen in the hands of an Indian began to be called “tomahawk.” It is almost impossible to determine the real meaning of a word in such conditions. As a result, after some time, "tomahawk" became the name only for battle axes, which were used by the indigenous people of North America.

For some time after the arrival of the first colonists, the Indians used only their own stone weapons. The situation began to change precisely at the instigation of the Europeans: they began to present their own axes as gifts, and the local population liked them. The Indians found them too heavy for use in battle, but for household needs, strong and durable metal tools turned out to be quite suitable. In addition, the opportunity to exchange an iron ax with Europeans saved local residents from the long and labor-intensive task of making stone analogues.

Meanwhile, there were more and more colonists. At the beginning of the 17th century, other settlers appeared alongside the British: the French, the Dutch, and the Swedes. Gradually settling across the territory of the North American continent - deep into Virginia and New England, up the Hudson and Delaware rivers to Hudson Bay - the scale of contacts with the local population also increases. And, according to data from the surviving lists of gifts for the latter, iron axes of various types were among the most desirable things.

It is interesting that over the years the huge demand for these tools has not died down, and the price of European goods has grown in direct proportion to the distance from the coast of the continent. So, for example, today you can find information about how in the middle of the 18th century in the Montreal area it was possible to exchange one beaver skin from the Indians for two axes, and to the west of the Great Lakes they could get more than three skins for one ax.

Such popularity of axes led to transformations both in the appearance of the weapon and in the technology of its manufacture. The production underwent a number of simplifications and began to look like this: an iron strip was bent to form an eye under the ax handle, then the ends of this strip were connected, after which the ax blade was forged. To obtain higher quality tomahawks, a steel plate was inserted between the ends of the strip, which improved the efficiency of the cutting edge.

The ax itself also changed: to satisfy the needs of potential owners, they began to make them lighter so that they could be used in battle. In addition, during the transformation process, several new types of iron tomahawks were made: tube, celt, espontone, with a point, etc.

Entire states skillfully took advantage of the demand for axes among the North American indigenous population. Thus, the representative of the British Empire in North America, William Johnson, noted that in 1765 the North Indian Department needed to receive ten thousand axes to sell to the Indians. But in general, over two centuries, the colonial empires sold or donated hundreds of thousands of weapons.

The Indians were very adept at using purchased or obtained iron tomahawks during battle. Basically, the reason for such effectiveness of the battle ax in the hands of the savage warrior was their long tradition of using ball-shaped clubs as striking weapons in battle. Therefore, back in the 17th century, the tomahawk, more than other types of weapons, terrified all potential and real opponents of the local population.

Today we also have information about exactly how the Indian ax was used in battle. Ethnologist Wayne Van Horne conducted research on skeletons that showed signs of damage from a tomahawk. Noting that the area of wounds was mainly limited to the skull, collarbones, ribs and forearms, he concluded that the most common attack method was a slash to the head. That is, damage to the collarbones appeared if the blade passed through the blade, and on the forearms - in cases where the victim tried to defend himself with his hand.

The tomahawk had such enormous popularity and respect among the indigenous population of North America that even the spread of firearms, the battle ax remained a priority among the Indians. It's all about offensive and combat tactics. After firing a gun or musket, it had to be reloaded, but often there was simply no time for this, and the previously formidable weapon became a cumbersome and inconvenient club. Therefore, after the shot, the Indian often took up his favorite tomahawk. In addition, the latter, unlike the same “firearms,” did not make thundering sounds and were an ideal weapon during surprise attacks on the enemy or neutralizing duty officers and guards.

Interesting fact: the tomahawk, like any element of an idealized image, has acquired its own arsenal of myths. One of the most common misconceptions, which can often be seen in films about Indians, is that tomahawks were used as throwing weapons. In fact, an ax is generally difficult to throw, especially at a moving target. Moreover, such use of a tomahawk is simply irrational, because in this case the Indian was left without a weapon.

The history of the tomahawk in the vast North American continent was long and full of interesting details. The Indian battle ax has come a long way and gained such overwhelming popularity that with the extinction of the indigenous cultures of the continent, it did not go into oblivion along with them. The colonial empires adopted the experience of the Indians and provided part of their own reconnaissance units with axes instead of sabers. Moreover, the history of the formidable weapons of the savages of North America continues today - tactical tomahawks, modernized with the latest technology, are part of the weapons of the US Army.

Modern army tactical tomahawk.

Source

Recommended viewing:

Helmets of the Scythian time and How to make imitation chain mail from a hose with your own hands

More than a thousand years ago, the Mayans abandoned one of their capitals, Tikal. Now we know why.

"Mars thorn"

The use of tomahawks: the beginning

Europeans, having studied the Indian ax, realized that it was more convenient and effective for close combat than a knife or spear. This is due to the design feature of the tomahawk. The Indian ax had a short handle used as a lever. This made it possible for a weakened or wounded soldier to use this weapon. The length of the handle made it possible to wield the tomahawk in a crowd or in one-on-one combat.

Based on the existing design, the Europeans, replacing sharp stone with iron, created their own significantly improved military weapons. It began to be actively used during boarding and close combat. It was also used to hit targets at a distance. The tomahawk throwing ax became an effective weapon, hitting a target at a distance of up to twenty meters. At the same time, the Indians themselves were trained in the art of war. They acquired professional skills, which made it possible for them to carry out military operations using a tomahawk. The ax became an element of combat and hunting equipment. It was used if it was necessary to finish off a shot animal.

Ease of use made the tomahawk (axe) very popular among the local population. The photo below shows the external design features of the product.

Making a handle for a tomahawk

Typically, ax handles are made of birch, but for a tomahawk it is better to choose a different wood. Cold Steel uses hickory wood for its tomahawk handles. In our latitudes, the best wood for an ax is ash. It is not inferior in strength to oak and at the same time has good flexibility. You can use dogwood, pear and cherry plum.

The combat tomahawk is a legendary weapon of the North American Indians with European roots. A well-made ax will help you on a hike and will not let you down in any life situation.

Author of the article:

ULFHED

I am interested in martial arts with weapons and historical fencing. I write about weapons and military equipment because it is interesting and familiar to me. I often learn a lot of new things and want to share these facts with people who are interested in military issues.