T-100 (in a number of documents also Izdeliye 100 or simply 100) is an experienced Soviet double-turret heavy tank of the late 1930s. One of the last Soviet tanks with a multi-turret design. Together with the experimental double-turret heavy tank SMK, which was similar in characteristics, and a prototype of the KV-1 heavy tank, the T-100 underwent front-line testing in battles on the Mannerheim Line during the Finnish War. Based on the results of testing, the tank was not accepted for service and was not mass-produced.

The design of a heavy tank, which was supposed to be used as a replacement for the T-35, was developed at the design bureau of the Experimental Mechanical Engineering Plant No. 185 named after S. M. Kirov in Leningrad in 1938 under the leadership of S. A. Ginzburg. E. Sh. Paley was the leading designer of the T-100. The layout of this vehicle was reminiscent of the SMK heavy tank, being its competition model; the difference was in the chassis. The experimental T-100 was manufactured in 1939.

The hull of the T-100 tank was made of rolled armor plates and cast parts, which were connected by welding, riveting and bolts. Anti-ballistic armor provided protection at a range of less than 500 m from enemy fire. The T-100 had two cast conical turrets, which were located one after the other; on the large turret was installed a commander's turret of circular rotation, equipped with viewing slots along the entire perimeter and equipped with a DT anti-aircraft machine gun. It should be noted that, according to the original design, three towers were supposed to be installed on the T-100. The front turret was armed with a 45 mm cannon and a machine gun, and the rear turret was armed with a 76 mm cannon and a machine gun. Another machine gun was located in a ball mount in the rear of the upper turret. The T-100 had telescopic sights. The undercarriage consisted of a caterpillar track, gable support and support rollers, rear drive wheels with removable ring gears and cast guide wheels. The T-100 was equipped with a radio station designed for six subscribers.

It should be noted that in terms of basic tactical and technical indicators, the T-100 was superior to the T-35. The T-100's armament made it possible to conduct massive fire in various directions, and the armor fully met the requirements of the time. However, the T-100 also had a number of serious disadvantages, including primarily its large mass and significant size, design complexity and large crew. The T-100 was not put into mass production. The experimental T-100 took part in the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940. By this time, the tank's armament had been modernized - instead of the L-10 cannon of 76 mm caliber, the L-11 cannon of 76.2 mm caliber was installed on the combat vehicle. The design of the T-100 served as the basis for the development of the SU-100Y self-propelled artillery mount. In addition, there was a second version of the T-100 - the T-100Z tank, which was supposed to be equipped with a howitzer. The possibility of creating an armored engineering vehicle based on the T-100 was also considered.

History of creation

In 1938, two Leningrad design bureaus developed very similar projects for a new heavy tank with ballistic armor, intended to replace the T-35. The Kirov plant, represented by SKB-2, offered the SMK machine. The second project, called T-100, was developed at the design bureau of the Leningrad Experimental Mechanical Engineering Plant No. 185 named after S. M. Kirov under the leadership of S. A. Ginzburg. The leading designer of the machine was E. Sh. Polyei. In general, the T-100 was of the same type as the SMK tank and differed from the latter mainly in the type of suspension and armament. During 1938, all approvals and considerations in commissions and authorities of the SMK and T-100 projects took place simultaneously. Like the SMK, the T-100 was originally designed with a three-turret design with a 76 mm cannon in the main turret and two 45 mm tank guns of the 1934 model in two small turrets. But with the accepted armor thickness of 60 mm, the weight of the vehicle should not exceed 55-57 tons, so the number of turrets was reduced to two. (There is a legend that the decision to reduce the number of turrets was made personally by J.V. Stalin, who removed the rear turret from the SMK model presented to him and stated: “There is no point in turning a tank into an armadillo!” Another option is that Stalin asked, having removed the turret from the model: “ How much does such a tower weigh?" "Seven tons," they answered him. "So take these seven tons and better strengthen the armor!") In January 1939, the drawings of the T-100 and SMK were transferred to production. In accordance with the resolution of the Defense Committee of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR, the prototype T-100 was supposed to be manufactured by June 1, 1939, but its production was delayed for two months - the prototype was fully assembled only on July 31, 1939 and accepted by the commission for field testing , combined with factory ones. It was supposed, according to the program of the Autonomous Army Technical University of the Red Army, to complete the tests on January 3, 1940, but in connection with the outbreak of the Soviet-Finnish War, it was decided to further test the combat and driving characteristics in combat conditions, replacing the L-10 tank gun with the more advanced L-11. The tank was sent to the front and took part in its first battle on December 17, 1939 in the area of the Finnish fortified area of Hottinen.

Heavy and super-heavy tanks

The country's leadership and designers once again thought about strengthening the armor and armament of Soviet tanks (although work was never interrupted) as a result of the events in Spain. Earlier, simultaneously with the transfer of the T-35 tank into mass production, the issue of replacing it with an even more advanced tank was resolved. Work on the project began in May-June 1933. In parallel with the developments of domestic designers, the project of a 100-ton TG-6 tank (Grote design) and a 70-ton Italian tank were considered.

The Grote tank had 5 turrets, of which the main one was armed with a 107 mm gun, while the others were supposed to have 37/45 mm guns and machine guns. Domestic projects, developed by N. Barykov and S. Ginzburg, were 90-ton vehicles with 50-75 mm armor protection. The first tank according to the project was armed with two 107 mm, two 45 mm guns and 5 machine guns. The second differed only in armament - one 152 mm, three 45 mm guns and 4 machine guns, and one flamethrower in the rear turret. The options were considered successful, they were built in the form of models 1/10 life-size. But the production of the prototype was rejected.

Model of the Soviet super-heavy tank T-39-1

In 1937, the design bureau of the Kharkov Locomotive Plant (KhPZ) received the task of designing a new heavy breakthrough tank based on the T-35. The task was to create a three-turreted vehicle weighing 50-60 tons with 75-45 mm armor, armed with one 76 mm, two 45 mm cannons, two large-caliber and 6 standard tank machine guns. The new tank was supposed to use the transmission and chassis from the T-35. But by the beginning of 1938, they could only carry out a preliminary study of six versions of the new tank, differing in the placement of weapons.

In April 1938, it was decided to involve the Leningrad Kirov Plant (LKZ), as well as Plant No. 185 named after. Kirov. The first plant designed the SMK tank (“Sergei Mironovich Kirov”), the leading engineer of the vehicle was A. Ermolaev; the second is product 100 (or T-100), the leading engineer of the machine is E. Paley. By this time, the T-46-5 tank, which had anti-ballistic armor, had already been manufactured at the Kirov plant in Leningrad, under the leadership of engineer M. Siegel. Its armament remained at the level of the T-26 light tank. Speed 30 km/h, crew 3 people. With a total weight of 32.2 tons, the tank had 60 mm armor on the hull and 50 mm armor on the turret. He didn't make it into the series.

Soviet experimental tank T-46-5, 1937

Work on the SMK and T-100 tanks progressed quite quickly: the SMK was ready by May 1, and the T-100 by June 1, 1939. On December 9, projects for new vehicles and their models were considered at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks and the Defense Committee.

Soviet heavy breakthrough tank SMK. Karelian Isthmus, winter 1939

Three turrets were placed on the tanks one after the other so that the middle turret rose above the end turrets. Stalin did not like this and the rear turret was removed in order to use its weight to strengthen the armor. Both SMK and T-100 were similar in appearance and almost identically armed. The difference was in the suspension. The SMK used torsion bars (previously they were installed only on the experimental T-28 tank) - steel shafts with wheel balancers that worked to twist when the tank ran into an obstacle. The T-100 used a suspension with leaf springs, which were protected on top by an armored screen.

Soviet heavy breakthrough tank T-100, November 1939.

The tanks were built and submitted for testing, which began on the night of July 31 to August 1, 1939. At the same time, the designers of the T-100 considered it possible to develop on its basis an even more powerful T-100Z tank, armed with a 152 mm M-10 howitzer in the main turret, and a self-propelled gun armed with a 130 mm naval gun. At the Kirov Plant, in addition to the ordered SMK, a single-turret KV tank (Klim Voroshilov) was also developed by leading engineers A. Ermolaev and N. Dukhov. The tank had a shortened SMK chassis, 75 mm thick armor and, according to the original plan, two guns in the turret : 45 mm and 76 mm.

Soviet experimental heavy tank KV, September 1939.

Based on the results of tests in the fall of 1939, the new tank was put into service on December 19, and already on February 17, 1940 it was sent along with the SMK and T-100 tanks to the front of the Soviet-Finnish War. All three vehicles took part in the battles, and although they suffered some damage from 37-47 mm anti-tank guns, such guns were unable to penetrate their armor. When the SMK was blown up by a landmine while moving deep in the Finnish defenses, it was heavily damaged and abandoned by the crew, and could not be evacuated. But the Finns didn’t touch him either. And after breaking through the Mannerheim Line, the tank was again with us. To deliver the tank back to the factory, it had to be disassembled, and it was no longer assembled or restored at the factory.

Heavy tank KV-2

It turned out that the 76-mm guns of the KV-1 tanks were too weak to destroy enemy fortifications, so it was decided to urgently arm this tank with a 152-mm howitzer in a new larger turret - the KV-2 tank. There are few examples in the history of tank building when such a powerful weapon was mounted on a tank in a rotating turret. Doubts were expressed as to whether the chassis could withstand the recoil of a shot, but tests showed that the tank would be able to function, so 4 of these vehicles were made at the Kirov Plant. They were tested on the Karelian Isthmus, where they used concrete-piercing shells to shoot at point-blank granite gouges on the “Mannerheim Line”. When one of the tanks left the battle, there were 48 dents in its armor from armor-piercing shells, but none of them penetrated the armor. The KV-2 tank was put into service and until the second half of 1941 was mass-produced at the Kirov plant.

Back - Forward >>

| < Back |

Description of design

In terms of purpose, layout, general design and distinctive features, the T-100 was identical to the SMK and was a two-turret tank of a classical layout with a two-tier arrangement of weapons and projectile-proof armor. However, in detail the tank had a number of significant differences from the SMK.

Frame

The tank's hull was box-shaped and assembled from sheets of rolled armor, connected by welding, riveting and bolts. A massive semi-conical turret box was mounted under the main turret in the central part of the hull. The armor protection compared to the SMK was somewhat weaker - 60 mm, which, nevertheless, provided the tank with reliable protection from the fire of the anti-tank artillery that existed at that time (with a caliber of up to 47 mm) already at a distance of 500 m or more.

Towers

Two cast conical gun turrets were located one after the other along the longitudinal axis of the tank. The placement of towers, and, accordingly, weapons, is two-tiered. The first tier was formed by a small front tower with a horizontal rotation angle of 245 degrees. The second tier was occupied by the central main all-round firing tower. On the roof of the main tower there was a commander's cupola (also of circular rotation) with viewing slots around the perimeter and a DT machine gun with the possibility of anti-aircraft fire.

Armament

The main armament of the tank was the 76-mm L-10 (later L-11) tank gun, located in a mantlet in front of the main turret. The gun was intended to combat primarily enemy fortifications and pillboxes, as well as unarmored targets, but also had satisfactory armor penetration. Auxiliary artillery armament consisted of a 45-mm 20-K tank gun mounted in a small turret and intended to combat armored vehicles. Both guns used telescopic sights.

The ammunition load of the guns was 120 rounds for the 76 mm gun and 393 for the 45 mm gun.

Machine gun armament included three 7.62 mm machine guns, two of which were coaxial with guns, and the third was located in the commander's cupola on the roof of the main turret and could be used to repel air attacks.

The machine guns' ammunition capacity was 4,284 rounds in 68 disc magazines of 63 rounds each.

Engine

The T-100 was equipped with a V-shaped 12-cylinder carburetor four-stroke liquid-cooled GAM-34 engine with a power of 850 hp. at 1850 rpm. Ignition is from two magnetos.

Chassis

The tank's suspension is individual, with leaf springs without shock absorbers.

The chassis for one side consisted of eight gable track rollers with massed tires, five gable rubber-coated support rollers, a rear drive wheel with removable ring gears and a cast guide wheel. The idler tension mechanism is a screw type, controlled from the control compartment. The gearing is lantern. The caterpillar tracks are fine-linked, with an open joint, and the pins have locking rings.

Communication devices

For external communications, the tank was equipped with a standard tank radio station 71-TK-3. For internal communications there was a TPU intercom for 6 subscribers.

World War II in 1/48 scale

I had some free time and I finally reduced the existing drawings and sketches to 48th scale.Well, this is what the tank should look like:

Judging by these sketches, all the upper edges of the body are smoothed.

I started making the body:

Well, I assembled it and sanded the body blank:

I found some time to continue working on the hull - I installed the turret stand, marked the roof and cut through the air ducts:

I am slowly improving the stern:

A small continuation - I installed grids on the air ducts:

I continue to work on the roof of the hull - I welded the turret stand, simulated welds and gougons on the fixed part of the roof and installed fastening bolts on removable sheets:

I continue the assembly work on the hull: I welded the joints of the front plates with each other and with the sides, installed the collision angle and installed goujons at the joints of the plates:

I reproduced the welds at the junction of the side plates of the top of the hull:

I riveted the frames of the air duct grilles. I installed the driver and stern hatches for access to the transmission:

This is how I imagine the exhaust pipes (without armor yet). I think that both pipes could exit into one round hole in the roof.

I made cast armor for two exhaust pipes:

Here's an idea of what it would look like - a stamped elevation at the level of the engine (naturally, the connection points with the roof will be smoothed out) with a hatch cover:

Well, this is an option - just a hatch without stamping:

I lowered the stamping height a little. I modified and sanded the armor of the exhaust pipes. I change the rivets on the grilles to smaller ones.

Assembled blanks of small towers:

It can be seen that they are approximately the same size as the T-35 turrets:

Here's what the turrets look like on the hull, together with the stamping. I think it's fine.

I slowly started making masks for the small tower cannons. Here's a rough edit for now...

Well, I looked at the body, where I smoothed out the connection between the stamping and the roof and bolted the armor of the exhaust system:

I continue fiddling with small towers:

A short continuation - I finished, in general terms, the small towers:

Well, the test ball is the first cart from Vladimir’s castings. I know that the springs are not replicas - there are two converging springs, but no matter how hard I tried to do it, nothing has worked yet... One thing calms me down - the springs there will be covered with casings and not particularly visible...

Here's what happened:

I made a bracket and installed the support roller on the cart:

This is apparently how the cart axle mount will be located:

I estimated the cart in place:

So, I assembled a kit for the bot (without supporting rollers for now) to figure out how all this disgrace would look on the body...

The clearance, however, is wow...

I proceed from the available information that when designing the SMK, Kotin proposed using the T-35 chassis. It is logical to assume that the use of the standard T-35 chassis was meant. That's why I don't want to change the geometry of the carts.

No one knows what Kotin’s project actually looked like, and the location of the supporting rollers on the carts is the conjecture of the author of the picture. Having complicated the cart, the author had to reduce the height of the entire structure. So it turned out that it happened... When building the tank, I will proceed from the fact that standard T-35 bogies were used. I will move the mounting elements for the bogie axles higher - like on a standard T-35.

I decided to install tracks from the T-35 on the SMK-1. And “sew up” the sides with screens directly from the body, covering the upper branch of the caterpillar (at the same time I’ll save on the tracks - I’ll put them only where it’s visible, and I won’t have to deal with the carts too much...).

Without screens, such a suspension is practically useless - large dimensions and a rather complex design will cause primary damage in battle... And a tank with screens looks more powerful...

Today they brought me the first resin castings of the leading sprockets and other miscellaneous things - I was given Vladimir’s trowels and my own for casting. Sprockets (copies of IS-2) - on SMK-1. Enlarged rollers on the KV-4 (the first version with a thick flange). Sloth and road wheel on the T-100.

I found a little time to see how the T-35 tracks would fit on the sprocket. The tracks themselves are a different story... Each track is cleared of flash, the holes are cleaned, the edges are rounded, adjusted to the “neighbor”, and a comb is glued. In general, it’s a lot of work, but it’s much better than nothing... Therefore, thanks again to Vladimir for the tracks and other parts of the T-35.

Finally, I got tired of the tracks... Well, I started experimenting with armored screens.

The design is collapsible... for now...

Finished the second side.

Main tower in progress:

Comparison of the prototype with the real tank:

I puttyed and sanded the tower. From milliput he fashioned “blanks” for a cannon mask and a machine gun tide. When it hardens, I will modify it

Installed eyelets and access hatches on the body:

I corrected it a little. I'm waiting again for it to harden...

“Welded” the roof and the machine gun mount. I started making the movable part of the gun mask.

He placed eyelets on the roofs of small towers. It looks like that's it with small towers.

Rough sketch of a gun mask:

Well, I have finished the construction phase of this tank. During the construction there were many conflicting thoughts, but in the end, I formed an idea for myself and completed the construction.

The screens are glued to the chassis and are removed from the body along with it (for ease of painting), so, unfortunately, it will not be possible to replace the screens...

I was in a hurry to say “everything”...

I am finishing the tower:

- cut viewing slits

— installed pistol port plugs

— imitated a weld at the joints of the turret armor plates

Primed the model. It looks ok in my opinion...

PS . Unfortunately, construction was stopped at this point and the author does not have photographs of the painted model...

Source: https://panzer35.ru/forum/47-10408-1

Tests and combat use

By the end of autumn 1939, testing of the T-100 was in full swing - the tank had covered over 1000 km. After the start of the war with Finland on November 30, 1939, it was decided to send the SMK, T-100 and KV-1 tanks to the active army for combat testing in front conditions. Before being sent to the front, the T-100's armament was changed - instead of the 76-mm L-10 cannon, a more powerful L-11 cannon of the same caliber was installed[1].

The tanks were consolidated into a separate company of heavy tanks and assigned to the 90th tank battalion of the 20th heavy tank brigade, which fought on the Mannerheim Line.

T-100 crew in the first battle[2]:

- tank commander Lieutenant Astakhov Mikhail Petrovich,

- artilleryman Artamonov,

- artilleryman Kozlov,

- radio operator Smirnov,

- driver Plyukhin Afanasy Dmitrievich,

- reserve driver Drozhzhin Vasily Agapovich,

- mechanic Kaplanov Vladimir Ivanovich,

- Kashtanov V.I.

On December 19, 1939, a separate company of heavy tanks, together with the rest of the 90 brin 20 tbr, went on the offensive in the Summa-Hottinen area. The battalion's tanks successfully advanced and advanced beyond the line of Finnish pillboxes, where the SMK hit a mine. The T-100 crew tried to tow the SMK with the help of their tank, but these attempts were not crowned with success. After this, the T-100, standing next to the SMK and covering it with increased artillery and machine-gun fire, ensured the evacuation of the crew from the damaged tank - the SMK crew moved inside the T-100 through emergency hatches in the bottoms of the vehicles. At the same time, the tank received at least seven hits from 37-mm and 47-mm anti-tank guns from a distance of less than 500 m, but the armor was never penetrated[2].

In the same battle, the engine of the T-100 stalled - the thread of the magneto adjusting coupling was cut. However, the tank driver was able, using one magneto instead of two, to start the engine again and continue the task.

After this battle, the T-100 was sent to the rear for engine repairs and returned to the active army on February 18, 1940. From that day until the end of hostilities, the T-100 operated as part of the 20th (22.02 - 01.03) and 1st (11.03 - 13.03) tank brigades. During this time, the tank covered 155 km and received 14 hits from anti-tank gun shells (6 on the left side, 3 on the main turret niche, 3 on the left track, and one each on the mantlet of a 45-mm gun and the left sloth). In all cases the armor was not penetrated. In total, by April 1, 1940, the T-100 had covered 1,745 km, of which 315 km were during the battles on the Karelian Isthmus [3].

After the end of the Finnish War, the T-100 returned to the factory, where the engine was completely replaced and light repairs were made to the tank[4].

In the summer of 1940, the tank was transferred for storage to Kubinka. After the start of the Great Patriotic War, the vehicle was evacuated first to Kazan, and then to Chelyabinsk, where the T-100 was transferred to the pilot plant No. 100. The tank remained at the plant until the end of the war, and then its traces are lost. According to some reports, until the mid-1950s, the T-100 stood in the backyard of the Chelyabinsk Tank School, and then, apparently, was melted down[5]. However, according to other sources, the tank did not survive to the end of the war - at the end of 1943, along with the T-29, KV-7 and a number of other prototypes of armored vehicles, it was cut into metal[6].

SMK is a Soviet experimental heavy multi-turreted tank. Received its name after Sergei Mironovich Kirov. It became the basis for the development of the KV, one of the most successful heavy tanks of the Great Patriotic War. History of creation

The Spanish War showed that all Soviet tanks needed significantly increased armor protection. This requirement especially applied to heavy tanks, so in 1938, the Kirov plant began to develop the SMK heavy tank, and at the Leningrad plant, in parallel, they began to develop the T-100. The work was carried out on a competitive basis - only one of the two tanks was to be accepted for service.

Until August 1938, tanks were only at the project stage. Finally, an order was received to produce a sample of the QMS by May 1, 1939. During the design and manufacturing process, it was decided to abandon one of the three towers, and work also began on a single-tower version - the future. In January 1939, the production of the tank in metal began.

SMK toured the plant for the first time on April 30th. On August 1st, comparative field tests began with the T-100 and KV. The SMK passed the tests, but it was noted that the vehicle was quite difficult to drive, and the commander did not cope well with fire control from two guns at once.

As a result, by December 1939, the SMK's mileage was 1,700 km. Serial production of the car never began.

general information

Classification – heavy tank;

- Combat weight - 55 tons;

- The layout is classic, double-tower;

- Crew – 7 people;

- Quantity issued – 1 piece.

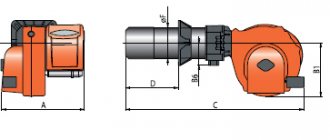

Dimensions

Case length – 8750 mm;

- Hull width – 3400;

- Height, mm 3250

- Ground clearance, mm 500

Reservation

Type of armor - rolled homogeneous steel;

- Body forehead – 75 mm;

- Hull side – 60 mm;

- Hull stern – 55 mm;

- Bottom – 20-30 mm;

- Housing roof – 30 mm;

- Turret forehead – 60 mm;

- Gun mantlet – 60 mm;

- Turret side – 60 mm;

- Turret rear – 60 mm;

- Tower roof – 30 mm.

The caliber and brand of the gun are 76 mm L-11 and 45 mm 20K;

- Gun type - tank;

- Barrel length - 30 calibers for L-11, 46 calibers for 20K;

- Gun ammunition is 113 and 300, respectively;

- BH angles: +35°/-7° (76 mm) and +25°/-7° (45 mm);

- GN angles: 360° (main tower) and 270° (small tower);

- Sights - telescopic TOP mod. 1930, periscope PT-1 mod. 1932

- Machine guns - 4 × 7.62 mm DT, 1 × 12.7 mm DShK.

Engine type - V-shaped 12-cylinder carburetor liquid cooling GAM-34;

- Engine power – 850 hp;

- Highway speed – 34.5 km/h;

- Speed over rough terrain – 15 km/h;

- Cruising range on the highway – 280 km;

- Cruising range over rough terrain – 230 km;

- Suspension type – torsion bar;

- Specific ground pressure - 0.662 kg/cm²;

- Climbability – 37 degrees;

- The wall to be overcome is 1.1 m;

- The ditch to be overcome is 4 m;

- The fordability is 1.7 m.

Machine evaluation

The report on field tests of the T-100, dated February 22, 1940, noted that the T-100 tank fully complied with the specified performance characteristics. The disadvantages were the unstable operation of the cooling system, poor reliability of the fan, and poor design of the cooling grids. It was also recommended to refine the gearbox control mechanisms and strengthen the design of the onboard clutches. The presence of a pneumatic tank control system was noted as an advantage.

Despite the general compliance of the tank with the requirements put forward, the commission found it inappropriate to recommend the T-100 for adoption, since the KV tank was superior to it in terms of basic performance characteristics.

At the same time, the design bureau of the T-100’s “native” plant No. 135 believed that the tank should have been recommended for adoption, since it was a vehicle of a different class compared to the KV. This was partly true - the T-100 was primarily an assault tank and could be used to mount more powerful assault weapons, such as 152 mm and 130 mm guns, while the more versatile KV could only carry a 76 mm gun. However, the engineers’ opinions were not listened to and the T-100 was never put into service.

True, an attempt was made to strengthen the T-100’s weapons. In January 1940, Deputy People's Commissar of Defense, First Rank Army Commander M. Kulik, gave appropriate instructions. It was supposed to install a 152-mm M-10 howitzer on the tank, capable of effectively dealing with gouges. In March 1940, a new turret with an M-10 howitzer was manufactured for the T-100, which was supposed to be installed on the tank instead of the existing one. The resulting modification was supposed to bear the index T-100-Z

. However, instead of this vehicle, the KV-2 tank was adopted.

Overall, the T-100 was a fairly successful machine. The tank, in principle, corresponded to the operational-tactical views on its use. The tank's armor also met the requirements, and the weapons made it possible to conduct massive and maneuverable all-round fire simultaneously in different directions. In all respects, the T-100 was significantly superior to the T-35. However, the tank also had disadvantages typical of multi-turret tanks, such as its large size, large crew, and difficulty in production. Like the SMK, the T-100 represented a necessary step on the way from heavy tanks with a multi-turret design to a new type of heavy tank, such as the KV-1.

Unrealized projects of vehicles based on the T-100

| This page is proposed to be combined with Object 103, Object 0-50, T-100-Z. Explanation of reasons and discussion - on the page Wikipedia: Toward unification/August 31, 2015#T-100 (tank) and Object 103, Object 0-50, T-100-Z . |

- T-100-X

is a heavy self-propelled gun armed with a 130-mm B-13-IIs naval gun in a fixed wheelhouse (in many ways similar to the SU-100-Y). - T-100-V

is a heavy artillery support tank. Armament: 203 mm B-4 howitzer gun in a rotating turret. - T-100-Z

is a heavy artillery support tank. Armament: 152 mm M-10T howitzer and 45 mm 20K cannon in two turrets. - Object 0-50

is a heavy breakthrough tank. Armament: 76 mm L-11 cannon and 45 mm 20K cannon in one turret. - Object 103

is a heavy coastal defense tank with a 130 mm B-13-IIs cannon in a rotating turret.

Main modifications of the T-100 tank

T-100 (“Product 100”) is an experienced heavy tank. Twice took part in the battles on the Karelian Isthmus in 1939-1940.

T-100Z (“Product 100Z”) is a heavy tank project designed under the leadership of L.S. Troyanov (leading engineer E.Sh. Paley) using the T-100 tank chassis at the end of 1939 - beginning of 1940. In April 1940, the main turret with weapons was manufactured. The production of the experimental tank was stopped in favor of fine-tuning the KV tank. It differed from the T-100 tank only in the new hexagonal turret, assembled from 60 mm thick armor plates connected by goujons, and the installation of a 152.4 mm M-10 howitzer in the mask installation of the main turret. The tank's ammunition load was 50 152.4 mm rounds for the howitzer and 393 45 mm rounds for the cannon and 4,284 rounds for machine guns.

Read: Soviet super-heavy tank “Object 103”

“Object 0-50” is a heavy tank project designed under the leadership of I.S. Bushnev (leading engineer I.I. Agafonov) based on the design of the T-100 tank in 1939. In the summer of 1939, a wooden model of the tank was made. In 1940-1941, a prototype tank was manufactured. But due to the deployment of serial production at the LKZ of the KV tank, work on the Object 0-50 tank was stopped.

It differed from the T-100 tank:

— the tank crew consisted of four people; — placement of the main armament in one turret, with a armor thickness in the frontal part of 75 millimeters; - in the mask installation the following were installed sequentially: 76.2 mm L-11 cannon, 12.7 mm DK machine gun or 45 mm cannon mod. 1934, 7.62 mm DT machine gun; — the power plant used a four-stroke twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled diesel engine V-2 with a power of 500 hp; — the chassis used a blocked, four balancing bogies with two road wheels, a torsion bar suspension.

Literature

- Kolomiets M.

Multi-turret tanks of the Red Army. Part 2. - M.: LLC "Strategy KM", 2000. - 80 p. — (Front illustration No. 5-2000). — 1500 copies. — ISBN 5-901266-01-3. - Kholyavsky G. L.

Encyclopedia of tanks. - Minsk: Harvest, 1998. - 576 p. — 5000 copies. - Arkhipova M. A.

Armored vehicles of the USSR of the Second World War. - Minsk: Harvest, 2005.

| Small tanks | T-33 · | |

| Escort tanks | "Renault-Russian" · "Motor ship AN" · | |

| Maneuverable tanks | T-12 · T-24 · · | |

| Breakthrough tanks | GUVP*/GUVP** · | |

| Chemical tanks | XT-26 OT-27/XT-27 MHT-1 · OT-37/HT-37 · HT-130 · HT-133 · | |

| Engineering tanks | ST-26/UST-26 · | |

| Light self-propelled guns | "Arsenalets" · T-27M · | |

| Medium and heavy self-propelled guns | 152-mm coastal self-propelled gun Tolochkova · | |

| Light armored vehicles | dietary supplement-1 · D-8/D-12 · FAI · | |

| Medium armored vehicles | BA-27 · D-9 · D-13 · | |

| Heavy armored vehicles | BA-5 BA-11 | |

| Floating armored vehicles | dietary supplement-2 · | |

| Chemical armored vehicles | D-18/37 · | |

| Self-propelled guns on a car chassis | SU-12/SU-1-12 · SU-4 · 29K · | |

| Armored personnel carriers | D-14 · | |

| Armored tractors | AT-42 · "Pioneer" · T-20 "Komsomolets" · T-26T | |

| Armored snowmobile | Grokhovsky's combat snowmobile | |

| Motorized armored carriages | D-1 · D-2 · KZ-1 ("Red Star-1") · MBV | |

| Armored railcars | D-37 · BTC · DTR · · BD-39 · BD-41 · Leningrad armored handcar | |

| Italic experimental samples and those that did not go into mass production were identified | ||

Excerpt characterizing the T-100 (tank)

Pierre often later recalled this time of happy madness. All the judgments that he made about people and circumstances during this period of time remained true for him forever. He not only did not subsequently renounce these views on people and things, but, on the contrary, in internal doubts and contradictions he resorted to the view that he had at this time of madness, and this view always turned out to be correct. “Perhaps,” he thought, “I seemed strange and funny then; but I was not as mad then as it seemed. On the contrary, I was then smarter and more insightful than ever, and I understood everything that is worth understanding in life, because ... I was happy.” Pierre's madness consisted in the fact that he did not wait, as before, for personal reasons, which he called the merits of people, in order to love them, but love filled his heart, and he, loving people for no reason, found undoubted reasons for which it was worth loving their. From that first evening, when Natasha, after Pierre's departure, told Princess Marya with a joyfully mocking smile that he was definitely, well, definitely from the bathhouse, and in a frock coat, and with a haircut, from that moment something hidden and unknown to her, but irresistible, awoke in Natasha's soul. Everything: her face, her gait, her gaze, her voice - everything suddenly changed in her. Unexpected for her, the power of life and hopes for happiness surfaced and demanded satisfaction. From the first evening, Natasha seemed to have forgotten everything that had happened to her. Since then, she never once complained about her situation, didn’t say a single word about the past and was no longer afraid to make cheerful plans for the future. She spoke little about Pierre, but when Princess Marya mentioned him, a long-extinguished sparkle lit up in her eyes and her lips wrinkled with a strange smile. The change that took place in Natasha at first surprised Princess Marya; but when she understood its meaning, this change upset her. “Did she really love her brother so little that she could forget him so quickly,” thought Princess Marya when she alone pondered the change that had taken place. But when she was with Natasha, she was not angry with her and did not reproach her. The awakened force of life that gripped Natasha was obviously so uncontrollable, so unexpected for her that Princess Marya, in Natasha’s presence, felt that she had no right to reproach her even in her soul. Natasha gave herself over to the new feeling with such completeness and sincerity that she did not try to hide the fact that she was no longer sad, but joyful and cheerful. When, after a nightly explanation with Pierre, Princess Marya returned to her room, Natasha met her on the threshold. - He said? Yes? He said? – she repeated. Both a joyful and at the same time pitiful expression, asking for forgiveness for her joy, settled on Natasha’s face. – I wanted to listen at the door; but I knew what you would tell me. No matter how understandable, no matter how touching the look with which Natasha looked at her was for Princess Marya; no matter how sorry she was to see her excitement; but Natasha’s words at first offended Princess Marya. She remembered her brother, his love. “But what can we do? she cannot do otherwise,” thought Princess Marya; and with a sad and somewhat stern face she told Natasha everything that Pierre had told her. Hearing that he was going to St. Petersburg, Natasha was amazed. - To St. Petersburg? – she repeated, as if not understanding. But, looking at the sad expression on Princess Marya’s face, she guessed the reason for her sadness and suddenly began to cry. “Marie,” she said, “teach me what to do.” I'm afraid of being bad. Whatever you say, I will do; teach me... - Do you love him? “Yes,” Natasha whispered. -What are you crying about? “I’m happy for you,” said Princess Marya, having completely forgiven Natasha’s joy for these tears. – It won’t be soon, someday. Think about what happiness it will be when I become his wife and you marry Nicolas. – Natasha, I asked you not to talk about this. We'll talk about you. They were silent. - But why go to St. Petersburg! - Natasha suddenly said, and she quickly answered herself: - No, no, this is how it should be... Yes, Marie? This is how it should be... Seven years have passed since the 12th year. The troubled historical sea of Europe has settled into its shores. It seemed quiet; but the mysterious forces that move humanity (mysterious because the laws determining their movement are unknown to us) continued to operate. Despite the fact that the surface of the historical sea seemed motionless, humanity moved as continuously as the movement of time. Various groups of human connections formed and disintegrated; the reasons for the formation and disintegration of states and the movements of peoples were prepared. The historical sea, not as before, was directed by gusts from one shore to another: it seethed in the depths. Historical figures, not as before, rushed in waves from one shore to another; now they seemed to be spinning in one place. Historical figures, who previously at the head of troops reflected the movement of the masses with orders of wars, campaigns, battles, now reflected the seething movement with political and diplomatic considerations, laws, treatises... Historians call this activity of historical figures reaction. Describing the activities of these historical figures, who, in their opinion, were the cause of what they call the reaction, historians strictly condemn them. All famous people of that time, from Alexander and Napoleon to m me Stael, Photius, Schelling, Fichte, Chateaubriand, etc., are subject to their strict judgment and are acquitted or condemned, depending on whether they contributed to progress or reaction. In Russia, according to their description, a reaction also took place during this period of time, and the main culprit of this reaction was Alexander I - the same Alexander I who, according to their descriptions, was the main culprit of the liberal initiatives of his reign and the salvation of Russia. In real Russian literature, from a high school student to a learned historian, there is not a person who would not throw his own pebble at Alexander I for his wrong actions during this period of his reign. “He should have done this and that. In this case he acted well, in this case he acted badly. He behaved well at the beginning of his reign and during the 12th year; but he acted badly by giving a constitution to Poland, making the Holy Alliance, giving power to Arakcheev, encouraging Golitsyn and mysticism, then encouraging Shishkov and Photius. He did something wrong by being involved in the front part of the army; he acted badly by distributing the Semyonovsky regiment, etc.” It would be necessary to fill ten pages in order to list all the reproaches that historians make to him on the basis of the knowledge of the good of humanity that they possess. What do these reproaches mean? The very actions for which historians approve of Alexander I, such as: the liberal initiatives of his reign, the fight against Napoleon, the firmness he showed in the 12th year, and the campaign of the 13th year, do not stem from the same sources - the conditions of blood , education, life, which made Alexander’s personality what it was - from which flow those actions for which historians blame him, such as: the Holy Alliance, the restoration of Poland, the reaction of the 20s? What is the essence of these reproaches? The fact that such a historical person as Alexander I, a person who stood at the highest possible level of human power, is, as it were, in the focus of the blinding light of all the historical rays concentrated on him; a person subject to those strongest influences in the world of intrigue, deception, flattery, self-delusion, which are inseparable from power; a face that felt, every minute of its life, responsibility for everything that happened in Europe, and a face that is not fictitious, but living, like every person, with its own personal habits, passions, aspirations for goodness, beauty, truth - that this face , fifty years ago, not only was he not virtuous (historians do not blame him for this), but he did not have those views for the good of humanity that a professor now has, who has been engaged in science from a young age, that is, reading books, lectures and copying these books and lectures in one notebook. But even if we assume that Alexander I fifty years ago was mistaken in his view of what is the good of peoples, we must involuntarily assume that the historian judging Alexander, in the same way, after some time will turn out to be unjust in his view of that , which is the good of humanity. This assumption is all the more natural and necessary because, following the development of history, we see that every year, with every new writer, the view of what is the good of humanity changes; so that what seemed good appears after ten years as evil; and vice versa. Moreover, at the same time we find in history completely opposite views on what was evil and what was good: some take credit for the constitution given to Poland and the Holy Alliance, others as a reproach to Alexander. It cannot be said about the activities of Alexander and Napoleon that they were useful or harmful, because we cannot say for what they are useful and for what they are harmful. If someone does not like this activity, then he does not like it only because it does not coincide with his limited understanding of what is good. Does it seem good to me to preserve my father’s house in Moscow in 12, or the glory of the Russian troops, or the prosperity of St. Petersburg and other universities, or the freedom of Poland, or the power of Russia, or the balance of Europe, or a certain kind of European enlightenment - progress, I must admit that the activity of every historical figure had, in addition to these goals, other, more general goals that were inaccessible to me. But let us assume that so-called science has the ability to reconcile all contradictions and has an unchanging measure of good and bad for historical persons and events. Let's assume that Alexander could have done everything differently. Let us assume that he could, according to the instructions of those who accuse him, those who profess knowledge of the ultimate goal of the movement of mankind, order according to the program of nationality, freedom, equality and progress (there seems to be no other) that his current accusers would have given him. Let us assume that this program was possible and drawn up and that Alexander would act according to it. What would then happen to the activities of all those people who opposed the then direction of the government - with activities that, according to historians, were good and useful? This activity would not exist; there would be no life; nothing would have happened. If we assume that human life can be controlled by reason, then the possibility of life will be destroyed. If we assume, as historians do, that great people lead humanity to achieve certain goals, which consist either in the greatness of Russia or France, or in the balance of Europe, or in spreading the ideas of revolution, or in general progress, or whatever it may be, it is impossible to explain the phenomena of history without the concepts of chance and genius. If the goal of the European wars at the beginning of this century was the greatness of Russia, then this goal could be achieved without all the previous wars and without an invasion. If the goal is the greatness of France, then this goal could be achieved without revolution and without empire. If the goal is the dissemination of ideas, then printing would accomplish this much better than soldiers. If the goal is the progress of civilization, then it is very easy to assume that, besides the extermination of people and their wealth, there are other more expedient ways for the spread of civilization. Why did it happen this way and not otherwise? Because that's how it happened. “Chance made the situation; genius took advantage of it,” says history. But what is a case? What is a genius? The words chance and genius do not mean anything that really exists and therefore cannot be defined. These words only denote a certain degree of understanding of phenomena. I don't know why this phenomenon happens; I don’t think I can know; That’s why I don’t want to know and say: chance. I see a force producing an action disproportionate to universal human properties; I don’t understand why this happens, and I say: genius. For a herd of rams, the ram that is driven every evening by the shepherd into a special stall to feed and becomes twice as thick as the others must seem like a genius. And the fact that every evening this very same ram ends up not in a common sheepfold, but in a special stall for oats, and that this very same ram, doused in fat, is killed for meat, should seem like an amazing combination of genius with a whole series of extraordinary accidents . But the rams just have to stop thinking that everything that is done to them happens only to achieve their ram goals; it is worth admitting that the events happening to them may also have goals that are incomprehensible to them, and they will immediately see unity, consistency in what happens to the fattened ram. Even if they do not know for what purpose he was fattened, then at least they will know that everything that happened to the ram did not happen by accident, and they will no longer need the concept of either chance or genius. Only by renouncing the knowledge of a close, understandable goal and recognizing that the final goal is inaccessible to us, will we see consistency and purposefulness in the lives of historical persons; the reason for the action they produce, disproportionate to universal human properties, will be revealed to us, and we will not need the words chance and genius. One has only to admit that the purpose of the unrest of the European peoples is unknown to us, and only the facts are known, consisting of murders, first in France, then in Italy, in Africa, in Prussia, in Austria, in Spain, in Russia, and that movements from the West to the east and from east to west constitute the essence and purpose of these events, and not only will we not need to see exclusivity and genius in the characters of Napoleon and Alexander, but it will be impossible to imagine these persons otherwise than as the same people as everyone else; and not only will it not be necessary to explain by chance those small events that made these people what they were, but it will be clear that all these small events were necessary. Having detached ourselves from knowledge of the ultimate goal, we will clearly understand that just as it is impossible to invent for any plant other colors and seeds more appropriate to it than those that it produces, in the same way it is impossible to invent two other people, with all their past, which would correspond to such an extent, to such the smallest details, to the purpose that they were to fulfill.