This term has other meanings, see Saber (meanings).

19th century French saber

Saber

- cutting-cutting and piercing-cutting bladed weapons. The saber blade, as a rule, is single-edged (in some cases with a one-and-a-half sharpening) and has a characteristic bend towards the butt. The average length of the blade is 80-110 cm. Sabers in various modifications were widespread in Eastern Europe and Asia in the period from to the 20th century as the main bladed weapon of cavalry and partly infantry. According to the main physical characteristics, the so-called “Japanese sword” is also a saber. In Western Europe, the saber became widespread quite late, in the 14th–19th centuries. Due to a number of its fighting qualities and ease of use, the saber has partially or completely replaced swords and other types of bladed weapons in many European countries.

Etymology

The Russian word “saber” possibly comes from Template:Lang-hu from Template:Lang-hu - “cut, cut”[1]. Perhaps it is an earlier borrowing from the Turkic languages cf. with Tatar “chabu” (the form in the Western dialect is “chabu” / “tsabu”, in the middle - “shabu”) I mow || mowing II 1) chop, chop off, cut/cut || cutting 2) hollow out/hollow out (trough, boat) 3) cut down, cut through (ice, ice hole). In the ancient Turkic language the word “sapyl” meant “to stick.” (DTS, p.485) There is also a common Turkic word sabala, shabala - with the transition of meanings: (cutting and piercing tool)> plow blade> shovel with a long handle for cleaning the plow> bucket with a long handle. In Chuvash - sabala, Tatar - shabala, Turkish - sapylak, Tuvan - shopulak, Altai - chabala. There are also versions of origin from the Turkic sap

- “handle, handle” (

sapy

- “having a handle”) and sapy - “to wave” (DTS, p. 485) In the Circassian language, the word “saber” comes from Kabard.-Cherk. sable (Se - “knife”, Ble - “snake” - a knife similar to a snake), also because of this, a connection with the Circassian deity Shiblya (thunder god) is visible, that is, the meaning of the word saber can be understood as “punishing (cutting) hand.”

Polish probably also comes from Hungarian. szabla

, and German

Säbel

, from which the French and English word

sabre

[2].

“Sabres in the scabbard!”: the crisis of the Russian cavalry of the second half of the 19th century

What could be more beautiful and poetic than a cavalry charge in such an ugly and unpoetic matter as war? But the prose of life took its toll. After the Crimean War, European armies acquired faster-firing and longer-range weapons, infantry and artillery could now create a “wall of fire” in front of the front, and cavalry... remained the same.

Its helplessness in the new conditions was clearly demonstrated by the wars of 1866 and 1870–71. The cavalry attacks became pointless and cost many casualties, but one of them was especially memorable. At the Battle of Mars-la-Tour on August 16, 1870, Prussian General Adalbert von Bredow famously said, “It will cost what it costs.”

and led seven squadrons of his 12th Cavalry Brigade in an attack on the French battery. Bredov's squadrons were able to pass through the ravine so that they were noticed only at the last moment. The Prussians flew into the battery and cut down the gun servants. Bredov managed to inflict significant losses on the enemy, but a counterattack by the French cavalry forced him to retreat, and out of 804 German horsemen, only 421 returned from the battle.

In the Napoleonic era, no attention would have been paid to this episode, but against the backdrop of the more than modest results of other German cavalry units, Bredov’s attack looked like an outstanding success. What soon became known as "Bredov's death ride" became a symbol of cavalry valor and a beacon of hope for those who believed that the days of the cavalry were not yet numbered.

E. Detaille and A. Neuville. The dead lancers of the 16th regiment and the cuirassier of the Seydlitz regiment from the 12th cavalry brigade. Fragment of the panorama “Battle of Resonville” (Mars-la-Tour). 1882–1883 Source – histoire-fr.com

American experience

Russian military minds closely followed the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and the discussions it generated. Contrary to popular belief, both in Russia and in the world they understood that combat conditions had changed, and great changes were coming in military affairs. However, what

and

what to

change for was unclear.

For the cavalry, the American option seemed very tempting. During the American Civil War of 1861–65, cavalry, although completely different from European cavalry, played a huge role and, through long, devastating raids, largely decided which way the scales would tip. Through the efforts of professors of the Academy of the Russian General Staff A.N. Vitmer and A.E. Stankevich, the experience of the war between the North and the South received great attention in Russia and was scientifically processed (which cannot be said about the rest of continental Europe). The further implementation of the American experience was undertaken by a young student of the Academy, Captain Nikolai Nikolaevich Sukhotin.

N. N. Sukhotin Source – genrogge.ru

In 1874, Sukhotin successfully defended his dissertation on raids based on the American Civil War, and two years later the “American style” raid was first tested on maneuvers in the Warsaw Military District. A small detachment of cavalry slipped through the guard line of the mock enemy, covered 144 kilometers along forest paths in 44 hours and took the crossing of the Vistula behind enemy lines. The task of the maneuver was completed, but the people were so exhausted that some began to hallucinate. It became clear that if the Russian cavalry intended to use raid tactics, then it should be prepared not for fast and dashing attacks, but for grueling horse marches.

The following year, 1877, the war with Turkey began, which confirmed the correctness of the direction taken by Sukhotin and his supporters. Adjutant General I.V. Gurko, quite in the spirit of North American raids, captured Tarnovo in a swoop, occupied the key Shipka Pass and began to devastate the lands beyond the Balkan Mountains, causing panic in Istanbul. However, when the epic near Plevna began, other cavalry commanders appeared on the scene, who not only could not prevent the delivery of food to the besieged Turkish garrison, but even ensure that the basic duties of the cavalry were performed. The commander-in-chief of the Russian army, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder, became furious when one of the cavalry commanders placed guards behind

infantry and did not move him forward, citing the lack of orders.

N. G. Schilder. Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder in the chief's uniform of the Life Guards Sapper Battalion and field marshal epaulettes. Late 19th century Source – wikipedia.org

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 began and ended with two brilliant cavalry operations, but otherwise the Russian cavalry was only a pale shadow of its former self. At the end of the war, Gurko’s feat was repeated by Major General A.P. Strukov, whose cavalry captured Adrianople with its military warehouses with a lightning-fast rush from Sheinovo. There was both a cavalry crisis and ways to resolve it: now the cavalry had to learn to act independently, using its speed, to capture or destroy enemy strongholds and disrupt his communications - in a word, to carry out the very raids that Sukhotin advocated.

Reforms

There is some irony in the fact that during the reign of Alexander III (1881–94), famous for its conservative attitude, the military decided to radically reform the most conservative branch of the army - the cavalry. After 1881, Sukhotin’s influence in staff circles reached its apogee - he became the closest assistant to the Inspector General of the Cavalry, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder, and a professor at the Academy of the General Staff. It is quite noteworthy that the reforms associated with the name of Sukhotin began with symbols.

If Peter I began his reforms by shaving beards, then his descendant Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich on April 26, 1881 allowed them to be worn in the cavalry - this became an unkind sign for adherents of cavalry traditions. Soon sabers were replaced with checkers, and then the sultans on hats were abolished. But the real blow to the cavalry spirit was dealt on July 13, 1882 - on this day all hussar and lancer regiments were renamed dragoons with a corresponding change in uniform. Only the guards regiments managed to defend the old uniform.

On the left is a private of the Pavlograd Hussar Regiment (before the reform), on the right is a chief officer of the Pavlograd Dragoon Regiment (after the reform) Sources - byzantine-way.livejournal.com and wikipedia.org

You can often hear that the hussar dolman did not suit the heavy figure of Alexander III, and this allegedly became the reason for the abolition of the magnificent form of the hussars and lancers. However, Sukhotin’s personality was no less significant. He began serving in 1863 in the Starodub Dragoon Regiment, and the dragoons (in the old days - simply “riding infantry”) did not have the characteristic cavalry luster. After entering the Academy, Sukhotin never returned to duty, working in the headquarters and at the department. Far from old traditions, he easily decided to abolish things that had deep symbolic meaning for Russian cavalrymen.

Thinking strictly rationally, Sukhotin was right a thousand times over. The difference between the types of cavalry had long since disappeared, and the cavalry acted like dragoons - that is, combining foot and horse formation. By dressing all army regiments in dragoon uniforms, uniformity in clothing and getting rid of unnecessary and very expensive elements were achieved. The savings were considerable - the uniform reform made it possible, without damaging the treasury, to increase the number of cavalry, transforming the regiments from 4 squadrons to 6 squadrons and forming several new regiments.

During the 1880s, reforms deepened. The cavalry was armed with rifles, learned rifle techniques and actions on foot. At large maneuvers, endurance and reconnaissance skills were tested. It seemed that the cavalry was finally rejecting the traditional ramming blow ( "ramming"

, as they then expressed among cavalry reformers) and learned to act “strategically,” that is, in the theater of combat operations, and not on the fields of individual battles. Plans were cherished in the event of war with Germany to disrupt faster German mobilization with a large-scale cavalry raid in the first days of the war. If such an operation was successful, the cavalry could provide an invaluable service to Russia.

N. S. Samokish. From the album “Volynian maneuvers of 1890” Source – humus.livejournal.com

Reaction to reforms

Despite all their efforts, Sukhotin and Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder quickly encountered what almost all Russian reformers face - reforms carried out on paper were brought to life with great difficulty.

The abolition of the beloved form caused a storm of indignation among the former hussars and lancers. This sensitive blow coincided with the transfer of many cavalry regiments to the borders of Germany and Austria-Hungary. It is not difficult to imagine the feelings of yesterday’s hussar, who was deprived of his bright uniform and the historical name of the regiment, after which the young man was sent to remote Jewish towns, where there was neither high society nor entertainment. A real exodus of wealthy and educated officers, who constituted its best element, began from the cavalry. It got to the point that some regiments had to transfer officers from the infantry.

General V.A. Sukhomlinov admitted in his memoirs that he burst into tears when he received the Pavlograd Hussar Regiment, which had recently been renamed the Dragoon Regiment. Opponents of the Sukhotin reform did not spare black paint in their memoirs, so today it is difficult to imagine the reaction to the reforms among the cavalrymen as a whole. Apparently, they parted with the heavy and clumsy sabers without much regret, receiving convenient checkers. The replacement of the carbine with a rifle did not cause protest either. The carbine did not allow it to stand up to infantry on equal terms in a firefight, but, unfortunately, a bayonet was attached to the dragoon rifle. The cavalrymen's rejection of this infantry attribute was also more symbolic than rational. The bayonet, attached to the scabbard of the saber, became a kind of symbol of the passion for foot combat in the cavalry and a sign that the cavalry had turned into “riding infantry.”

N. S. Samokish. From the album “Sketches of N. Samokish from the life of the Guards Cavalry.” 1889 Source – forum.artinvestment.ru

Let us not forget the fact that the introduction of the bayonet meant the addition of a new section of training to the already extensive cavalry training program. In accordance with the “Instructions for conducting training in the cavalry” of 1884, the cavalryman had to acquire the skills of riding, caring for a horse, handling bladed weapons and firearms, operating on horseback and on foot, guard and reconnaissance service, combining all this with training “ literature" and literacy studies. This was a very extensive program, and if we remember the illiteracy of the Russian peasant recruit, the flight of educated officers from the cavalry, and add to this the reduction in the service life in the cavalry from six to five years, which occurred in 1888, we will get a more or less complete picture difficulties in training cavalrymen.

However, the grumbling but obedient officers did not present such an obstacle to reform as the bosses, ossified in the routine of the good old days. Since the time of Nicholas I, if not earlier, the Russian cavalry has become accustomed to valuing two things - correct seating in the saddle and fat bodies of horses. In the 1880s, these ancient customs had not yet been eliminated, and any squadron commander remembered that “for unsatisfactory performance on the right, three (purely manege formation, which was used to check the fit of people in the saddle and had no combat value - author’s note) are taken away squadrons, but all other branches of service are considered less important and do not entail any penalties or severe criticism...”

It was required that the horses appear at the inspection

“round, like barrels,”

which was achieved by complete neglect of work and increased distribution of fodder for a month before the visit of the authorities.

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich demanded multi-mile raids, district commanders demanded reconnaissance and security, and brigade chiefs wanted to see fat on the bodies of horses. Perspicacious officers noted that the increased attention to the seating of the cavalrymen and the body of the horses was explained by the banal laziness of the authorities, because both could be checked in the arena without leaving the place. The contrition of one of the then experts in cavalry affairs, F.F. Gryaznov, is understandable, who wrote that “with us, no instruction can come into force immediately, but we must wait until almost an entire generation has been re-educated

.

Conservatives are winning

And generations did change, and by the end of the 1880s new people with new ideas came onto the scene. Fans of raids never had a monopoly in the world of military thought, and when the lessons of the Franco-Prussian and Russian-Turkish wars were somewhat forgotten, their influence began to decline.

N. S. Samokish. From the album “Volynian maneuvers of 1890”. Presumably, General A.P. Strukov is depicted in the foreground Source – humus.livejournal.com

In Europe at that time, it was customary to brush aside the American experience that inspired the “raidmen,” citing the great difference in the conditions of warfare and the lack in the United States of decent (by European standards) cavalry capable of a ramming attack. When, after 1878, the American experience nevertheless made its way into Russia (which, by the way, never happened in other countries) and, to a certain extent, influenced the abolition of the hussar and uhlan regiments, the conservatives did not give up and used the above arguments. In their opinion, the Americans simply staged cowboy shootouts, and the European cavalry, with its centuries-old traditions and chivalrous spirit, is capable of more. In 1887, captain N.A. Villamov wrote on the pages of the “Military Collection”:

“As for us personally, we are deeply convinced that if, on the one hand, modern weapons have made the chances of success of a cavalry attack, usually accompanied by relatively greater losses, somewhat more serious, then on the other hand, the result of a successful cavalry attack has now become more decisive, and his moral impression on the enemy should be even stronger, and precisely because of the infantry’s confidence in its invulnerability.”

Bredov’s attack, mentioned at the beginning of our article, came in handy here, which began to be cited as evidence that with proper preparation, a cavalry attack on infantry is still possible and effective. The speed with which cavalry could penetrate the sphere of actual fire seemed to be its advantage over infantry. Will yesterday's recruits and reservists with any perfect rifles resist the galloping mass of hanging pikes? Needless to say, behind the “cavalry renaissance” there were often anti-modernist sentiments that were popular at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

A group of officers and class officials of the Sumy Dragoon Regiment who took part in the celebration of the 250th anniversary of its formation. June 27, 1901. The Sumy regiment was one of the historical hussar regiments forced to change its uniform to a dragoon one Source – bulatovichclub.org

They did not close their eyes to the increased power of fire, but they believed that now it required from the cavalry an even more dashing cavalry spirit than in the old days. And to maintain this very spirit, symbols were needed. The same Villamov wrote:

“A person who is more elegantly and beautifully dressed is always more confident himself, and the consciousness that his appearance is admired gives rise to a desire in him to show himself as a fine fellow in other respects; This human weakness, inherent in intelligent people, is especially characteristic of our common people.”

These hints clearly read: “Bring back the old form!” The cavalrymen needed faith in their own strength, while during maneuvers the cavalry, which dared to attack the infantrymen, was forced to retreat and was considered defeated, implicitly teaching them the idea of the impossibility of defeating the infantry. According to conservatives, the rifle occupied too much space in the cavalry training program, and thereby instilled the idea that it was the main weapon of the cavalryman. At the same time, saber cutting fell into decline. The question of returning the pike to the cavalrymen, a cumbersome burden during a strategic raid, but necessary in a closed cavalry attack, was increasingly raised. In addition, supporters of “ramming” fiercely repulsed an attempt to introduce shooting from horseback in the cavalry.

The dispute between conservatives and “raidomaniacs” was resolved in a very banal manner. In 1890, after a long mental illness, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder died. His son, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Younger, who after some time received the post of inspector general of cavalry, did not share the passion for raids, and Sukhotin’s influence on “equestrian affairs” came to naught.

N. S. Samokish. Transbaikal Cossack Source – russiancossacks.getbb.ru

The sad epilogue to “raid mania” was the failed raid on Yingkou during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, which was mockingly called the “creep.” A raid on German territory to disrupt mobilization had by that time turned into a fantasy, since the Germans covered their eastern borders with small fortresses, which became an insurmountable barrier for the Russian cavalry. And yet, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the cavalry regulations of all the great powers confidently stated that “despite all its effectiveness, the rifle cannot replace the effect produced by the speed of the horse, the magnetism of the mounted attack and the horror of cold steel.”

.

Obviously, during the heated battles of the “raidomaniacs” and supporters of the “ramming”, the most important thing was missed, that for which the cavalry was still indispensable - reconnaissance. Some Russian military leaders were quite clearly aware of this fact. So, this caught the eye of General A.N. Kuropatkin back during the Pskov maneuvers of 1903. In his diary he wrote:

“All the infantry units of the two armies wandered in the dark, since little corps cavalry was left with them. At the same time, the cavalry of the two sides, consisting of 12 regiments, formed, as usual, a rather disorderly equestrian list. I took this opportunity to once again report to the sovereign about our passion for strategic (army) cavalry.”

Kuropatkin’s fears were confirmed by both the Russo-Japanese War and the maneuver period of the First World War. Looking for an opportunity on the battlefield, as before, to play first fiddle, the cavalry lost sight of the necessary role of the “eyes and ears” of the army. The price for this was the blindness and deafness of the Russian armies on the fields of Manchuria and East Prussia and, as a consequence, a series of heavy defeats.

N. S. Samokish. Recreation of dragoons Source – artpoisk.info

List of sources:

- Sukhotin N.

Raid of a flying detachment beyond the Vistula. Episode from cavalry maneuvers // Military collection. 1876. No. 11. - Hasenkampf M. _

My diary. 1877–78 St. Petersburg, 1908 - Fuller W.

Strategy and Power in Russia. 1600–1914. The Free Press. 1992. - Sukhomlinov V. A.

Memoirs. Memoirs. Mn., 2005. - Nortsov A. N.

Memories of His Majesty’s Pavlograd Life Hussars (1878–1880). Tambov, 1913. - Terekhov A.

Cavalry notes // Military collection. 1889. No. 5. - Gryaznov F.

Cavalry conversations // Military collection. 1889. No. 6. - Villamov

, rotm. Concerning the most significant issues of cavalry technology // Military collection. 1887. No. 10. - Jarymowicz, R. J.

Cavalry From Hoof to Track. (2008). - Kuropatkin A. N.

Diary of General A. N. Kuropatkin. M., 2010. P. 145.

Design

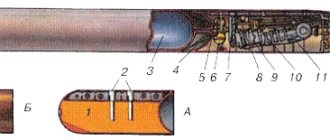

The structure of the saber

A. Hilt (hilt) ( kryzh

) B. Blade

C. Outpost ( first third, barrier, strong part of the blade

) D. Middle part of the blade (

bend, base

) E. Feather (

weak part of the blade, upper third

)

1. Pommel ( knob

) 2. Handle (

handle

) 3. Crosshair 4. Cross (

guard, flint

) 5. Blade 6. Butt (

blunt

) 7. Golomen (

blade plane

) 8. Dol 9. Elman 10. Point

The main parameters of a saber are the length of the blade, defined as the length of the axis drawn from the tip to the point where the blade (or heel) ends and the tang begins. The length of the perpendicular dropped from the highest point of the blade's bend to this axis determines the curvature. Other important parameters are the distance from the tip to the end of the tang and the total length of the saber with the hilt, as well as the width of the blade and the thickness at the butt.

Story

Saber of the 12th century, Eastern Europe Sabers in the miniature of the Radziwill Chronicle of the 15th century

The saber appeared in the 7th century among the Turkic peoples, as a result of a modification of the broadsword. Single-edged broadswords in mounted combat had an advantage over double-edged swords due to their lighter weight, and also had a technological advantage.[3] The appearance of a bend in the blade, small at first, made them sabers. Since the middle of the 7th century they have been known in Altai[4], in the middle of the 8th century - in the Khazar Khaganate and spread among the nomads of Eastern Europe. The average length of the blade of the first sabers was about 60-80 cm. Often the handle in relation to the blade was at some angle (5-8°). It is also characteristic that the appearance of sabers was everywhere accompanied by broadswords or swords with inclined hilts. The arm protection was a simple diamond-shaped guard. Often the end of the saber was double-edged by 10-20 cm, which increased its piercing properties. However, the saber was a primarily chopping weapon, and its piercing properties were secondary. There is another opinion regarding the tilt of the handle and the origin of the saber. In particular, there is a tilt of the hilt as a whole, and not of the handle. The hilt was tilted towards the blade using a special clip located between the blade and the cross. The equivalent in Japanese weapons is the habaki. The prototype of the saber was a cranked Turkic knife, in the second. floor. VII century extended to a broadsword, which in the beginning. VIII century takes on a bend and turns into a saber. The first blades that can be called sabers were found in kuruk near the village. Voznesenki (now Zaporozhye) in Ukraine. The evolutionary impetus for the appearance of the saber is the use of a special clip between the crosspiece and the blade, changing the ratio of the axes of the hilt and the strip[5].

At the end of the 10th century, sabers from nomads came to Rus', which was associated with the formation of the Russian cavalry, and soon became widespread. Since the 11th century in southern Rus', sabers have become no less important weapons than swords. In the north they reach as far as Minsk, Novgorod and Suzdal Opolye, but there they are not so widespread. By the 10th century, the length of the blade of Eastern European sabers increased to 1 meter, and the curvature to 3-4.5 cm. Their width was 3.0-3.7 cm, thickness about 0.5 cm. From the second half of the 11th to the 13th centuries, the average length the blade increases to 110-117 cm, the curvature is up to 4.5-5.5 cm, the average width is 3.5-3.8 cm; Moreover, some known blades had a curvature of 7 cm and a width of 4.4 cm.[6]

The design of the saber handle was lighter than that of the sword. The cheren, as a rule, was made of wood, with a metal top (knob), usually of a flattened cylindrical shape in the form of a cap, put on the cheren. This pommel was usually equipped with a ring for attaching a lanyard. In the 9th-11th centuries, straight crosses with spherical crowns at the ends were common, which then curved towards the point. In the 11th century, diamond-shaped crosspieces, known from the first sabers, became widespread - the crosshairs increased the strength of the structure.[6]

In the 10th-11th centuries, sabers appeared in the Arab world, but at first they did not become so widespread there, experiencing competition from the usual straight bladed weapons. Since the 12th century, they have become more widespread in Iran, Anatolia, Egypt and the Caucasus. Their sabers of this time were similar to the Eastern European ones of the 10th century - the length of the blade is about 1 meter, width 3 cm, bend 3-3.5 cm, thickness 0.5 cm. In the 13th century, sabers in Islamic countries began to replace swords and broadswords. The Mongol invasion played a big role here. At the same time they end up in India. In the 15th-16th centuries, two main types of Islamic sabers emerged: narrow and long shamshirs with significant curvature, characteristic of Iran, and shorter and wider kilics with less curvature, characteristic of Turkey. Both options had a straight handle, a cross with a crosshair on the hilt, different weights, the average length of the blade was about 75-110 cm. By this time, the level of their production in Islamic countries had reached such an extent that the export of sabers and saber strips to other countries became significant, including Eastern European ones.[7]

In the 14th century, yelman on a saber became widespread, after which the saber acquired the properties of a predominantly chopping weapon. At the same time, sabers became the completely dominant long-bladed weapon in Rus'. In the Novgorod lands, however, sabers had not yet replaced swords, but still became widespread. The sabers characteristic of the 14th-15th centuries, which were in circulation in Eastern Europe, including Rus', the Caucasus and some other peoples, have not changed much compared to the 13th century: the length of the blade remains within 110-120 cm, the curvature increases to 6.5-9 cm. At the same time, rod-shaped crosses about 13 cm long with extensions at the ends, with an elongated crosshair, are finally becoming widespread.[8] The weight of sabers of this period ranged from 0.8 to 1.5 kg.

Far East

The first images of sabers appear on reliefs of the Han period (206 BC - 220 AD) in China. Presumably, these were experimental forms of blades that were not widely used in the region for a long time. Artifacts discovered in northern China date back to the Northern Wei period (386–534). Almost simultaneously, the saber ends up in Korea (a fresco from a Goguryeo tomb in Yaksuri, 5th century), and then in Japan. In certain periods, two-handed sabers, such as zhanmadao/mazhangao (China), nodachi (Japan), became widespread. In general, Far Eastern sabers differed significantly from Western ones and included a large variety of varieties. One of the differences was the design of the handle with a disc-shaped guard (Japanese tsuba, Chinese panhushou).[9]

By the middle of the 17th century. long two-handed sabers ( no-dachi

.

_

_ The reason for the preservation of this archaic relic in the Qing troops for such a long time is unknown, as is the extent of the prevalence of these types of sabers.

XIX century was marked by the emergence of a number of new types of bladed weapons - from Nuweidao

(oxtail saber), which appeared in the first half of the century and reached maturity by the 1870s, to several varieties of two-handed

dadao

, which appeared in the last quarter of the century and developed into the classic

dadao

, which was in service with the Kuomintang troops during the war with Japan 1937-1945.

Template:Also

Mongol Empire

The exact date of the appearance of sabers among the Mongols is unknown. The typology of early Mongolian sabers is also unknown. Most likely, sabers were used by proto-Mongol tribes since the Northern Wei Dynasty, but there is no information confirming their use. In the 13th century, according to the testimony of the Song envoy Zhao Hong, sabers became the most popular long-bladed weapon among the Mongols (however, they continued to use swords very widely, and even more so, broadswords). At this time, Mongolian sabers (modern Mongolian selem

) included two varieties: with a narrow blade, slightly curved and tapering towards the tip, and with a shorter and wider blade, slightly widening in the last third.

After the Mongol invasion of the countries of Central Asia, the armament of the Mongols changed significantly under the influence of the conquered peoples; In addition, a significant part of the Mongol troops were newly conquered Turkic tribes. However, in the 13th century, the Far Eastern influence on the design of Mongolian bladed weapons can also be traced - some sabers discovered by archaeologists have a disc-shaped guard. In the 14th century, in the west of the empire, a type of saber was established, distinguished by a long, wide blade of significant curvature with a saber cross that was standard by that time.[10]

Late Middle Ages

Saber by F. M. Mstislavsky, first half of the 16th century, Cairo

From the end of the 15th to the beginning of the 16th centuries, saber production in the Arab world reached such a level that it began to influence Eastern Europe, where imported “oriental” sabers became widespread. Kilichis of the Turkish type were distinguished by massive blades 88–93 cm long, with an elmanya, with a total length of the saber of 96–106 cm. The weight of such sabers with scabbards sometimes reached 2.6 kg. The crosspiece could sometimes reach up to 22 cm. The handle was usually made of a faceted wooden tube, put on a handle, equipped with a knob. Later, the pommel of the handle tilts towards the blade. Sabers with a relatively narrow blade without elmani, partly related to shamshirs of the Iranian type, and partly possibly preserving elements of sabers of the Horde time, had a total length of 92-100 cm with a blade length of 80-86 cm and a width at the heel of 3.4-3. 7 cm[11]

Local Eastern European sabers were also forged under Asian influence. However, from the second half of the 16th century, the development of the handle took place in Hungary and Poland. In the 17th century, a hussar saber with a closed hilt appeared from the Hungarian-Polish ones: from the side of the blade, from the end of the crosshair to the knob, there was a finger bow that protected the hand; this bow was sometimes not connected to the pommel of the handle. A thumb ring was added to the crosshairs, allowing for quick changes in the direction of strikes.[12] In Rus', such sabers were in use under Polish influence during the Time of Troubles.

In the 17th century in Rus', sabers were both locally produced and imported. Domestic ones, as a rule, were forged under foreign influence - in the inventories, sabers are distinguished for Lithuanian, Turkish, Ugric, Cherkassy, Kizilbash, German, Ugric, and also Moscow forging[13].

In the 16th-17th centuries, saber fencing techniques were formed. The Polish school of fencing was especially strong (Polish: sztuka krzyzowa

), which included several types of slashing and parrying. In Poland, the saber was a weapon primarily of the gentry, and was used more on foot than in mounted combat.[14] In Rus', sabers were used by the local cavalry, and later by some archers and reiters of the new system. The saber of B. M. Lykov-Obolensky, dating from 1592, has been preserved, many notches on which indicate his high fencing skills[15]. Sabers were the main long-bladed weapon of the Cossacks.

In the countries of Central and Western Europe, sabers became widespread in the second half of the 16th century, but first appeared in the 14th-15th centuries. This spread was not significant at first. In the infantry among the Landsknechts, the two-handed Grand Messer saber was in use, which appeared in the 15th century in Hungary, and used mainly in fencing schools, the Dusak. Starting from the second half of the 14th - first half of the 15th century and up to the 17th century, massive short sabers-cleavers were also used, possibly descended from falchions under eastern influence - kortelas (Template:Lang-it, Template:Lang-it, German kordelatsch

, German

kordalätsch

), malkus (Template:Lang-it), storta (Template:Lang-it), badeler (French

Template:Lang

), krakemart (French

Template:Lang

). In the 16th-17th centuries, a shortened “half-saber” - henger (English Template: Langi-en2) was in use. In general, during the 17th century, straight bladed weapons, such as the sword, were widely used in these countries, and sabers became widespread only in the 18th-19th centuries.[16]

New time

Russian naval officer's saber (left) model 1811, (right) model 1855.

Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineers and Signal Corps (St. Petersburg) American Cavalry Saber, 1905 In the 17th-18th centuries, under Eastern European influence, sabers spread throughout Europe. They came from sabers of the Polish-Hungarian type. Throughout the 18th century, they were used in various European countries, including England, being primarily cavalry weapons.[17]

In Russia, around 1700, Peter I changed the army and its weapons according to Western models. At the beginning of the century, sabers were used by dragoons. Under Peter II, half sabers appeared. In 1759, following the example of the Austrian cavalry, dragoons and mounted grenadiers were armed with sabers. In 1763, sabers were the weapons of the hussars. In 1775, all dragoons were armed with sabers (some previously had broadswords). In 1786, the grenadier regiments were re-equipped with sabers with a copper hilt, and among the rangers they were introduced instead of swords.[18]

During Napoleon's Egyptian campaign in 1798-1801, the French appreciated local sabers, after which they, and under the influence of French fashion, spread throughout Europe, Mamluk-type sabers. These sabers became standard weapons in England. In Russia, based on French models, infantry officer sabers of the 1826 model and dragoon sabers of the 1841 model were introduced. At the same time, Europe was influenced by the armament of the irregular regiments of the Russian army, which included Cossacks and Turks who took part in the Foreign Campaign. In the 19th century, sabers were used in all types of troops. Dragoons, hussars, and in some cases cuirassiers were armed with heavy cavalry sabers, while lancers and Russian irregular cavalry were armed with light ones. The navy used decorated officers' sabers and massive boarding sabers. A variety of designs were also common in the infantry.[17]

In the European armies of the New Age, sabers had blades of medium curvature (45-65 mm), hilts with bulky guards in the form of 1-3 arches or cup-shaped. The total length reached 1100 mm, blade length 900 mm, weight without sheath up to 1100 g, weight with metal sheath up to 2300 g. At the end of the 19th century, the curvature decreases to 35-40 mm and the saber again acquires piercing and chopping properties. At this time, Turkish and Japanese sabers began to be made according to European models.

In 1881, in Russia, checkers were adopted into service with the regular army, which, compared to sabers, had better attacking properties at the cost of reducing defensive ones and abandoning complex fencing techniques, which conscript soldiers were hardly taught anyway. Despite the fact that in terms of the shape of the blade they are sometimes close to early sabers, they are not classified as a variety of the latter. Sabers remained widespread even during the First World War, and after it they began to disappear from the arsenal of European armies due to the general rejection of edged weapons. Nevertheless, cavalry, and with it sabers and checkers, had little military significance until the end of the Great Patriotic War. Until 1945, on the one hand, Soviet cavalry corps and Polish cavalry took a very active part in the war, and on the other, German and Hungarian cavalry brigades and divisions, but their main and practically the only way, with rare exceptions, of participation in hostilities there was fire fighting while dismounted[19]. Sabers are still used as a ceremonial weapon in many countries.

Is a katana a saber or a sword? Expert opinion

“A katana is a saber because it has a curved blade,” some say. “The shape of the blade doesn’t mean anything,” others retort. So what is a katana and how to classify long-bladed weapons? Gunsmith, fencer, expert in Japanese martial arts Sergei Polikarpov dotted all the i's.

Someone will come out of the fog, take something out of his pocket, and only the ataman’s eye will immediately see who and what.

He blows without deception: In the shuyts there is a sharp katana (Something like a scimitar), And in the right hand there is a chisel. (Russian folk song) A person’s dignity is not determined by the length of his sword.

© Miyamoto Musashi

I’ll say right away: firstly, I believe that a katana is a sword. Secondly, it doesn't matter.

Let's start from the opposite point of view: “a katana is a saber.”

This position is based on the appearance of the object, exists in the nutrient medium of social networks and has its own specific population of carriers.

The latter are poorly familiar with Japanese culture, as well as with the military affairs of medieval Europe.

They believe that it is enough to classify weapons only by the shape of the blade, more precisely by its bend. Therefore, a long-bladed weapon with a curved single-edged blade and any handle is called a saber. A sword is one with a straight, double-edged blade and a guard in the form of a cross. Everything that does not fall into these descriptions has its own unique names: broadsword, rapier, colishemar, falchion, cleaver, sword, saber.

In the popular mind, a sword is always a connotation of high status, chivalry and culture, a symbol of heavenly romantic power. And a crooked saber is, they say, a vile Asian piece of iron that does not chop at all, but only cuts.

Straight and slightly curved blades

Straight and curved blades - why are they and is there a fundamental difference?

If you do not go into the details of the bend of the blade, the balance of the center of gravity of the weapon, the distribution of mass around this point, the location of the percussion point, speculation about the purpose of the elmani (expansion towards the end of the saber strip, in the so-called weak part of the blade, in the upper third of the blade from the tip, - Editor's note)

and other details - the fundamental difference between the use of straight and slightly curved blades is small.

The features and advantages of a straight double-edged blade with a symmetrical handle are obvious.

This is the maximum opportunity to cover the shortest distance to the target and the optimal shape for a direct injection. This is the ability to use a second sharp blade after the first one has become dull or chipped. It is important that the handle is symmetrical, otherwise it will not be possible to turn, hold the weapon and use the second blade. The advantages of a curved weapon are higher strength (the arch is stronger than a straight beam), the convenience of returning the blade after hitting the target, and the ability to inflict a thrust around obstacles.

As everyone who served in the Soviet army knows, if you put a howitzer on its side, you can shoot from around the corner.

The maximum curved - 30-45 degrees - blades of the Persian shamshir are most convenient to use at a distance of fist fighting; the shape of the weapon allows you to stab the enemy under the crown of the helmet and the hem of the armor, and most importantly - around the kalkan (shield), as if hammering boxing hooks and uppercuts.

For saber operation, the optimal handle is one with a smooth reverse S-shaped bend and a beak-shaped pommel, which prevents the weapon from slipping out. In addition, with equal dimensions of straight and curved blades, the latter is much more convenient and faster to remove from the sheath and put into it. For fencing and chopping this is not essential, but for daily wear it is very important.

An essential feature of the use of a saber is the presence of a lanyard (a belt, loop, cord or brush on the hilt of a bladed weapon. - Ed.). I would say more categorically - it is almost impossible to use a one-handed slashing weapon without a lanyard on horseback.

However, the similarities are more significant.

With one-handed blades, cleaving blows are applied with the weapon being carried and returned to the fighting position after closing the circular trajectory. The technique of saber fighting en gross is similar to techniques with a straight one-handed sword, so it is no coincidence that in the English army manuals of the 18th-19th centuries the same masters taught the same actions for the Hungarian saber and the Scottish broadsword. Fencing with a saber and broadsword is, as a rule, the use of feint, working ahead and parade-riposte.

Why is a katana a sword?

The Japanese katana (or Japanese tachi - the only difference is in the design of the mount details and the method of hanging it from the belt) is a two-handed sword with a slightly curved blade (the average depth of bend of an Edo blade is from one to three cm). Roughly or even strictly straight blades were often found.

The handle has neither a reverse S-shaped bend nor a beak-shaped pommel, characteristic of a saber. The guard is represented by a flat oval disk called “tsuba”; it provides the necessary protection for the hand and support when delivering a piercing blow.

The two-handed sword is capable of inflicting the most powerful and destructive damage, and it is fundamentally different in its use of leverage.

Obviously, the wider the hands are on the handle, the stronger the effect. This feature of a two-handed weapon allows you to complete the trajectory of a power strike at a certain point without the need to complete a circular movement. This makes it possible, for example, to convert a cutting action into a piercing action without support from another blade.

Even the first acquaintance with the techniques of traditional kenjutsu (“the art of the sword”) and the historical techniques of two-handed Langschwert immediately reveals their irresistible similarity. Almost identical fighting positions, similar principles of striking, indistinguishable methods of working in connection, striking with the pommel, techniques of confrontation in the clinch and frequent transition to fighting using the sword to throw to the ground or pinching a joint.

The medieval fighters of Europe and Asia were united by a common understanding. It is most likely impossible to kill a Kamakura samurai or a Burgundian gent d'armes clad in armor with a two-handed sword at all. The most likely scenario for a fight between two sword-killing armadillos would be to knock one to the ground, immobilize him on the ground and end the fight with an inseparable misericord (a dagger with a narrow blade section for penetration between the joints of knightly armor. - Ed.)

.

We read “The Tale of Yoshitsune” (an epic of the early 13th century) and find vivid descriptions:

“He drew his sword, three shaku nine sun in length

(shaku - approximately 30 cm, 1 sun - 1/10 shaku, total blade length is 117 cm. - Author's note);

the blade flashed like lightning above his head, and with a warlike roar he moved straight on the offensive...

Kakuhan walked towards him, roaring like an elephant polishing its tusks. And, like an angry lion, Tadanobu was waiting for him. And so Kakuhan swooped in, inflamed with a thirst for battle, and began to slash with enormous force right and left, as if trying to completely mow down the enemy...

Kakuhan, swinging his sword, opened his side, and, like a still stupid hawk diving into a cage for food, Tadanobu, bending his head, slid headlong forward and struck. Feeling the blow, the huge monk decided that the end had come for him, and profuse sweat appeared on his forehead (the blow to the shell did not lead to anything, the enemy was not wounded. - Author's note)...

He swung his sword and brought it down hard on the top of Kakuhan's helmet. He recoiled. Tadanobu, snatching a short sword from his belt, jumped up close to him and lunged. The tip hit the inside of the collar. ... Tadanobu twisted and struck again. The sword clanged on the collar's mounting plate, but Kakuhan's head remained intact.

(several blows to the helmet were ineffective. — Author’s note)…

And as he rose to his feet, Tadanobu swung and struck. ...The blow with a crash split the front part of Kakuhan's helmet along with the trim and cut his face in half. When Tadanobu pulled out the sword, Kakuhan collapsed as if knocked down."

.

There are even more similarities in the technique and tactics of using large swords from one and a half to two meters long between Japanese no-dachi and European montante.

The fighters, trained to wield such blades weighing from 2.5 to three kg, broke into the ranks of spearmen and single-handedly scattered enemy groups, like a bear scatters a pack of dogs. Thus, when it comes to long-bladed weapons, from a historical and functional point of view, the division into one-handed and two-handed is fundamental.

Classifying weapons based only on the shape of the blade seems short-sighted to me.

The katana, despite the presence of a bend, does not possess other, no less important properties of a saber.

The constructive and applied difference does not allow us to identify these objects.

The classic saber is the weapon of a light cavalryman. Its appearance and spread in Europe in the 17th century is associated with the popularity of the Hungarian hussars and then the Polish lance cavalry and the spread of cavalry combat in the hit and run style.

What's the terminology?

Weapons science, like any branch of historical knowledge, is greatly influenced by traditions, historical context and ideological connotations. Any scientific knowledge requires the introduction of basic concepts, and since history is not a narrowly national science, they must be valid in the international community.

As you know, terms are not discussed, they are agreed upon. Any terminology is hierarchical, and definitions should be short, convenient and understandable.

Imagine that you see a few hundred meters away from you the figure of a man with a long weapon in a sheath on his belt. At this distance it is impossible to accurately identify him, and you will simply say that he has a sword on his belt. Which one exactly - without clarification. And you'll be right.

Therefore, for example and discussion, let’s consider international (English) terminology. It uses a group concept that distinguishes the object from knives, daggers, axes and spears.

Any long-bladed weapon is a sword.

A traditional medieval sword with a straight double-edged blade, a simple cross, a coaxial one-handed hilt and a pommel is called an arming sword or knight sword. A two-handed/bastard sword is called a long sword or bastard sword.

A straight double-edged or single-edged blade (framed with a basket guard - basket hilt) is also a sword: broadsword or backsword. In Russian we use the Hungarian word “broadsword”. The handle can be straight or have a saber bend to enhance the emphasis on the palm.

To describe “ignoble” European swords with wide single-edged blades, sometimes curved along an axis, sometimes with a straight spine and a curved blade and coaxial handles of various types, there are traditional terms: messer, grossmesser (two-handed), falchion, dussac, cleaver, etc.

For national swords, such as Japanese tachi, katana, wakizashi, no-dachi or o-dachi, traditional national names are retained, which allow each of these items to be clearly identified. The classification of the Japanese sword within the local tradition has many typological problems, but now this is completely unimportant.

What is a saber? A saber is a one-handed weapon with a curved single-edged blade, a cross-shaped guard and a smooth reverse curve of the handle. Classic examples are the Persian shamshir, the Turkish kilic (the Europeans met them before anyone else and called them scimitar), the Hungarian and Polish saber.

Turkish kilic

A late medieval European one-handed sword with a developed guard with protective rings is a side sword (spada da lato in Italian), a sword constantly worn by the owner. It is sometimes called a transitional or early rapier. Such a sword is characterized by a long piercing-cutting blade and a complex basket-shaped or cup-shaped guard - an irresistible rapier, rapier sword, rapier, espada ropera.

Although... The French simply called the rapier a sword - l'epee, from the Italian spada (a long sword with a wide flat blade in ancient Rome was called spatha, the concept gave the Germans der Spaten, a shovel, and we got a spatula in Russian).

Reduction in size, reduction in combat and protective properties in favor of ease of wearing and indication of status - this is a costume sword, scarf sword or small sword, what in Russia since the 18th century was called a sword.

OPINION. Not really. In the 17th century, archers were already using swords. Moreover, this was a standard type of weapon - see the classic “... in all regiments of the Saldatsk and dragoon regiments, soldiers and dragoons and in the Streltsy Prikazakh, the Streltsy ordered to make a short pike, with a kopeck at both ends, instead of reeds, and long pikes in the Saldatsk regiments and in the Streltsy orders to carry out the same according to consideration; and he ordered the rest of the soldiers and the archers to have swords

.

And he ordered berdyshes to be made in regiments of dragoons and soldiers instead of swords in every regiment of 300 people, and the rest should continue to have swords. And in the Streltsy orders, inflict berdysh on 200 people, and the rest will remain in swords as before

.”

1659, however. By the way, where is the sword in international historical terminology?

And there is no sword here at all. Because we are discussing historical weapons, not modern sport fencing. In the IOC (International Olympic Committee), however, there is also no sword, there is also a sword - l'epee. In general, the word “sword” is an interesting one - we are well aware of its cognates: twine and spaghetti. There is no perfection in words.

Sergey Polikarpov

Manufacturing technology

The first sabers were an attribute of noble warriors and therefore, as a rule, were inlaid with gold and silver. The blades were produced using complex multilayer technologies, also typical for expensive swords, which involved welding iron and steel plates. In the 12th-13th centuries, sabers became more widespread weapons, and therefore their technology became simpler. Most blades were now produced by welding a steel blade or carburizing a solid iron strip.[6] Since the 12th century, sabers of Islamic countries were made from carburized blanks, which, as a result of special repeated hardening, received an ideal combination of toughness and hardness, and the edge of the blade was especially hard.[7]

Sabers made of Damascus steel were especially valued Expression error: unidentified punctuation symbol “[” Expression error: unidentified punctuation symbol “[” , however, they were expensive due to the complexity of production and the large waste of metal - a simple saber had quite sufficient strength, but at the same time it was much cheaper. The best and most expensive, and therefore rare, were damask sabers. For example, in the middle of the 17th century in Rus', an imported saber strip made of Persian steel cost 3-4 rubles, while a Tula saber cost no more than 60 kopecks[20].

From the second half of the 16th century in Europe, and from the middle of the 17th century in Rus', sabers from converted steel began to be produced.

The handle consisted of a handle, usually two wooden or bone plates, fastened with rivets to the shank. In other cases, a solid piece with a hole was put on the shank. In front, between the shoulders of the blade and the handle, a metal cross was fixed, providing protection for the hand. On Far Eastern sabers, the guard was not a cross, but a tsuba. Later European sabers featured more complex guards.

1

February 2, 1238.

The transfer itself occurs instantly and silently.

Just a moment ago, Andrei was aiming his butt at the German’s head, and the next second he found himself on the outskirts of a snow-covered village. Like the other members of their long-suffering group, he was on a narrow snow-covered road containing multiple horse hoof prints.

About twenty meters from where the tourists appeared, the first village buildings began. The village was small, with a total of twenty courtyards, but it was quite long, as it was located along a single road. The huts, covered with snow almost right up to the windows, and the courtyards attached to them stretched on opposite sides of the road and melted into the darkness. There was no light in any of the windows.

According to Andrey's estimates, the frost was about twenty degrees, but, perhaps due to the lack of wind, it was well tolerated.

The young man raised his head and was amazed at the sight that opened. The night sky shone with millions of bright stars, beautifully illuminating everything around.

The time machine software was set up in such a way that at the beginning of each new episode, all members of the tourist group, thanks to the return sensors implanted in the body, gathered in one place. Both the living and, in their case, the dead.

Andrei looked around at the survivors, there were only eight of them left. Around, in the snow, lay the mutilated bodies of Sveta and Alexei, and Edik was resting a little to the side with a bullet through his head.

Knowing that it was in vain, Andrei nevertheless sat down near the body of Nikolai Abramovich and whispered in his ear:

- I finished them off! “Then he searched the old man’s body in the vain hope of finding a gun.

He only did not find the Ryzhkovs, since their bodies had been burned in the camp crematorium before the transfer.

Having finished, I looked up and my soul brightened: everything was fine with Ksyusha.

Judging by the appearance of the survivors, Sashka spent his time in the camp “more fun” than anyone else. “They hit him hard in the face. Although he brought the best trophy,” Andrey drew attention to the machine gun he had just thrown behind his back.

- You look good!

Sashka smiled at Andrey with broken lips, revealing a hole instead of his upper left fang, and said peacefully:

- The main thing is to be alive! Although in this cold, I think it won’t last long. We must go to one of the houses, otherwise we will freeze.

- We can’t go to the village! — suppressing a sob, Larisa Nikolaevna entered the conversation. It was the hardest thing for her now: despite the age difference with Sveta, they were close friends.

- Larisa Nikolaevna is right! We must run away from the village, in about five minutes the attack will begin! - Ksenia supported her.

- Whose attack? - Sashka was surprised.

— Guys, have you read the tour program? — the girl asked a tired rhetorical question. — Attack of the Mongol forward patrol of one hundred people. They attack this village, in which, unfortunately for Vladimir, the governor planning reconnaissance stopped with fifty. The vigilantes did not expect an attack. Considering that they were deep in their rear, they neglected the security, relying on the villagers. And there were fewer of them - fifty-one people. With their swift attack, the Mongols took the Vladimir soldiers by surprise, did not even allow them to raise their armor, and cut them down on the threshold of their houses. And then they burned the village. Well, then everything is simple: without a governor, the prince’s sons convinced their mother to meet the Tatars not under the protection of walls, but in an open field. The result was complete destruction. And the city, when Batu’s Tyumen approached it, there was almost no one to defend. On February 5th the city was taken by storm, and Detinets fell on the sixth. It was this spectacle that we were supposed to witness. So, guys, if we don’t want to become not only witnesses, but also participants in these events, go to the forest.

There was a second pause, and then Andrey spoke:

- No, we can't run. Firstly, Sashka is right: we will simply freeze, this is not Austria, and we will end up in these rags in an hour. Secondly, even if we don’t freeze, we won’t run far without skis: around the village, as I see it, there are fields - and there’s waist-deep snow there. And finally, thirdly, even if we do escape from the Mongols now, then by the end of the day today, if I remember correctly, Vladimir will be under siege, and the entire area will be swarming with Tatar troops. We don’t know the surrounding area, where to hide either. It won't be difficult to catch us. But I have another plan. — Andrey fell silent mysteriously.

- Well, don’t be tormented! - Sashka begged.

- We stay here and take the fight. We have small arms: a rifle, a machine gun, and even a grenade. Enough bullets. I think they won’t trample with a drill if we knock down the front rows. Yes, the Vladimir people should arrive there too.

- Why do we need this? - the girl asked.

- If we save the governor, firstly, there will be somewhere to warm up, and secondly, there will be someone to organize the defense of the city, and therefore, the city will be able to hold out not for three days, but more, and there is a possibility that we will be transferred from here before the Mongols take the city and carry out a massacre in it. Sash, what do you say? You are our main firepower,” Andrey looked at Sashka.

- Yes, in general you say the point. I agree.

A minute later, the rest of the group expressed their agreement.

- Ksyusha, where will they come from?

“They’ll come straight at us along the road from the forest.” They will rely on the speed of the attack.

“Great, then I propose to take a position here,” Sashka pointed to the roof of the nearest barn, perpendicularly adjacent to the road on the left.

“I suggest that the rest of you, except Sasha and I, take shelter in that barn over there.” The men need to find at least some kind of weapon, so that if one of the Tatars breaks past us, they will have something to defend themselves with.

Everyone went to hide in the barn except Vasya and Larisa Nikolaevna.

Vasya broke a huge picket fence and took cover behind a barn, on the roof of which the young people were planning to take a position. He explained his action by saying that if someone came from the rear, he would meet them.

Larisa Nikolaevna came up with another idea: so that the Vladimir people would not cut them down in the heat of the moment, she, as the only one of all who could somehow speak Old Russian, decided to find the governor and warn him.

Using a snow-covered woodpile adjacent to the barn as a ladder, the young people quickly climbed onto the gable, shingled roof, discussing tactics along the way. Within a minute, having compacted a half-meter layer of snow, they built a bed on a slope opposite to the expected direction of the enemy’s appearance.

As it seemed to Andrei, such a position, on the one hand, provided protection of the entire body from arrows, and on the other hand, made it possible to fire by slightly rising and sticking the weapon over the ridge of the roof.

Having made himself comfortable, Andrei raised the rifle up and fired.

- What are you doing?

- Let the Slavic brothers rise up and prepare for battle.

Andrey said and began to watch the forest wall. Its edge was located about three hundred meters from their position. The cloudless starry sky perfectly illuminated the surrounding area, and after just a couple of minutes the young man was able to see how horsemen appeared from the forest and silently rushed towards the settlement.

- Began! - Andrei whispered, shaking the bolt of his rifle, his voice hoarse with excitement.

In response, Sashka bared his teeth with his creepy smile and replied:

- Yeah! With God blessing!

Pushing through the snowdrifts, the front ranks of the Mongol detachment finally emerged from the forest into the open. Holding their horses back a little, they gave the main forces the opportunity to catch up with them and after that, throwing their horses into a gallop, they went on the attack.

Ksyusha was not mistaken, and in full accordance with her words, the Tatars did not go around the village, but struck along the road. Bending down to the shaggy manes of their short horses, the Tatars were already rushing at full speed, leaving behind a trail of raised snow.

As they approached the village, the horse avalanche accelerated more and more. Very little time passed, and the distance separating the young people from the cavalry was no more than a hundred meters. Despite the fact that Andrei was on the roof of the barn, the cavalry rushing towards him made an eerie impression: the dull reflection of the armor, the bright reflections of sabers unsheathed, the clang of metal, evil faces in shaggy hats, the swirling snowstorm behind their backs and the gloomy silence of the attackers - all it painted a picture of an ancient nightmare come to life. Having difficulty suppressing the great desire to drop everything and run, Andrei squeezed the rifle tighter in his hands.

A warrior on a tall bay horse rushed ahead of the detachment, half a horse's corps away. A few moments before the collision, Andrei fixed his gaze on him. The rider was no more than twenty, his body was protected by a long chain mail shirt with scaled armor put on top, on his head was a shishak (pointed helmet) with an aventail, his left arm and half of his chest were covered with a red round shield with a spike in the middle, a saber was clamped in his right, pointing down to earth. The gaze of attentive eyes does not notice the young people, it is directed lower and somewhere behind their back.

All!!! The squad is about to burst into the sleeping village at full speed, now there is no point in hiding. On the contrary, it is necessary to make a noise so that the locals who do not understand anything, in an attempt to figure out what is happening, jump out of their houses to meet the sabers and arrows of the nukers. Like a single living organism, the Mongol detachment erupted from itself a battle cry:

- URGH!!!

This turned out to be too much for Sashka’s nerves, and in response to the roar of the Mongols, machine gun fire fell on the attacking cavalry.

When planning the battle, the young people were going to let the squad get closer in order to hit for sure, saving ammunition. Now, under the impression made by the attacking enemy, Sashka opened fire earlier. To be honest with himself, Andrei was grateful to him for this, since he himself could hardly restrain himself so as not to break down. As a result, by the time the battle began, the distance between him and the Mongol detachment was no more than fifty meters.

For the Mongols, the attack came as a complete surprise. Sashka’s first, longest burst, fired into the midst of the attacking detachment, felled five, one of whom was the one on the high horse. The bullet hit him in the stomach, knocking out sparks and several steel flakes. The nuker was folded in half, thrown from his horse under the feet of the rushing cavalry. The horse of the rider following him tripped over the body of the fallen man, and the rider flew out of the saddle and buried himself in a snowdrift.

Andrei did not lag behind: having caught sight of one of the soldiers approaching from the left, the guy fired. The bullet hit the shield opposite the covered left shoulder. A small piece of metal knocked the Mongol out of the saddle, spun him in the air and threw him to the ground.

Within a few seconds, the dead caused a “traffic jam” to appear in the middle of the advancing column, making it difficult for the subsequent column to move—the Mongolian detachment began to lose its striking power.

Unfortunately for the young men, the Mongols were not going to stop attacking. Skirting the flanks of a blockade of human and horse bodies, the Mongol warriors who had identified the threat rushed towards it.

Taking aim at the next warrior, Andrei rose above the ridge of the roof, and the next moment, with a buzzing sound, his cheek was burned by a fired arrow. Hissing, the guy belatedly ducked down. It was lucky that the arrow only cut the skin, and doubly lucky that it was under the eye and not above it. In a situation where you need to act against a large number of opponents, limiting your vision can easily result in death. Wiping away the blood with his sleeve, Andrei pulled the bolt of his rifle and, looking out from behind his skate, shot at the warrior with his bow raised. He had to shoot offhand, trying to get ahead of the Mongol who was aiming at him, but he couldn’t get ahead. And simultaneously with his shot, an arrow trembled opposite his stomach, entering the roof ridge almost to the very plumage. Andrey also missed, the bullet hit the horse in the head. The unfortunate animal somersaulted over its head, burying the archer under its body.

Out of the corner of his eye, Andrei saw how Sashka, who had previously been spraying the attackers with bursts, fell on his back and began to reload the machine gun. Trying to win his friend precious seconds, Andrei turned his attention to his sector of fire.

Three people posed the greatest danger at this moment. The first, having overcome the crowd, walked through the center. The other two came in to the left, from Sashka’s side. Andrey started with them. A shot - and one of the two fell out of the saddle. Another second and the rifle fires again, this time not so successfully. The rider was wounded in the leg and, under the influence of the destructive force of the bullet, flew off his horse. Without fussing, Andrei pointed at the last one, moving in the center and coming very close. He smoothly pulled the trigger, and a dry click announced that there were no more cartridges in the rifle.

As if in a slow motion movie, Andrei saw that the rushing warrior was directing his horse parallel to the building. Having caught up, he pushed off from the back of the animal, soaring onto the roof. He was still in the air, and the saber, raised above his head and held in his right hand, had already begun to move towards Andreeva’s head. The guy understood that he would not have time to do anything, and at that second the warrior landed on the roof of the barn. The roof slope, covered with old shingles, could not withstand the weight of a man dressed in armor. And with a loud crash, the nuker fell inside the building. Flashing a centimeter from Andrei's nose, the saber dug into the skate and, cutting it to the middle, got stuck, breaking out of the fingers of the failed warrior.

Having finally replaced the magazine, Sashka jumped up next to Andrei and with a short burst shot down another approaching horseman.

And then the picture of the battle changed. The Mongols, realizing that their attack had floundered and the effect of surprise had been lost, changed tactics and took up their bows. Having dispersed about a hundred meters from the position of the young people, they began a deadly round dance. Moving in a circle, the warrior closest to the barn shoots an arrow at him and rushes further, giving way to the next one. By the time he comes full circle, he has just enough time to take an arrow from the quiver and put it on the bowstring. This method of combat was in no way inferior to Sashka’s machine gun in terms of rate of fire, and a shower of arrows fell on the friends’ position.

The guys made an attempt to stop this deadly whirlwind, simply bringing down massive fire from two barrels on the enemy. However, as the distance between the riders increased and their mobility increased, the effectiveness of the fire dropped sharply, especially for Sashka.

Rising above the cover, Andrei fired offhand and took cover again. With a dull thud, two arrows entered the ridge. Now the Tatars do not give enough time to aim. It’s easier for Sashka, he shoots more and more often, sticking out only his hand with a machine gun from behind his skate.

When the surface of the roof next to Andrei's head shattered into pieces of shingles, he realized that their situation had turned from unimportant to critical. Hoping that the roof would be able to hold the arrow and protect their body, the young people did not take into account the enormous penetrating power of the composite Mongolian bows. If at first the enemies tried to hit the protruding shooters, then realizing that the roof covering was not able to protect against an arrow piercing through it, they concentrated their fire on the roof slope.

A minute later, there was no talk of any return fire; all the attention of the young people was spent on finding a safe place to escape from the arrows shooting through the roof.

- We need to get off the roof. “Sooner or later we’ll catch you here,” Andrei said, trying to hide behind the ridge of the roof.

- Let's get down - they'll stop. And the machine won't help. But you're right, you can't stay here. Let's go down, and there I will take a position on the opposite side of the road - we'll try to hold them there.

Sashka was the first to jump off the roof into the snow, and a second later Andrei landed next to him, only miraculously avoiding running into a protruding stick hidden by the snow.

They pressed their backs against the log house and, changing stores, Sashka said:

“I’ll rush across the road now, cover me.”

“We’ve agreed,” Andrei hissed, stuffing another clip into the rifle with wet hands.

“Where are the vigilantes?” - thought Andrei, fully aware that if help does not appear in the very near future, they will be finished. After a couple of seconds, driving a cartridge into the chamber, he said:

- Ready!

- Three four! - Sashka barked and jumped out of cover onto the road.

Without hesitation, raising his rifle, Andrei followed. The picture that opened did not promise anything good for him and Sashka. Having suppressed their fire, the enemy made another attempt to break into the village. And now the Mongol detachment was moving towards their friends at full speed.

The closest were two horsemen armed with spears. Andrei pointed his rifle at one of them, but Sashkin’s short burst (of three rounds) beat him to it. All the bullets found their target: two hit the shield of the nuker walking to the right, piercing both him and the owner. The last one went to the horse on the left. Having received a bullet in the chest, the horse stumbled, and the rider, flying over his head, hit the road hard and, by inertia, slid right under Andrei’s feet. The guy grabbed the rifle with both hands and struck the butt of the rifle in the back of the head as he rolled up the “gift.”

An arrow screeched next to Andrey, another entered the ground ten centimeters from his leg. In order to somehow hide, the guy fell to his knee, raised his rifle and shot at the next rider flying towards him at full gallop. He got it, but it didn’t change the situation - three more Mongols were flying towards him from different directions. Trying to pull the shutter, he already realized that he would not have time to fire the next shot and that he had only a few moments left to live. And then a strong blow to his right shoulder knocked him over into the snow. The saber of a nuker flashed overhead, cutting through the air as it rushed close.

Overcoming the terrible pain in his shoulder, Andrei knelt down from the ground where he had been knocked over by the arrow stuck in his shoulder. He raised his eyes and saw the face of his own death, distorted with rage, rushing towards him with a drawn saber.

- SLA-A-AVA-A-A!!! - was heard somewhere behind the young man, when his consciousness had already begun to fade. And the last thing he saw was Vasya’s face, pulling him out of the way of the attacking Russian squad.

Usage

Sabers served primarily as cavalry weapons, which predetermined their relatively large length and suitability for a chopping blow from above, to enhance which the weapon was balanced in the middle of the blade.

A sufficiently strong bend of the blade gives the chopping blow cutting properties, which significantly increases its effectiveness. When struck, the saber slides relative to the object being struck. This is especially important since the slash is always delivered in a circular path. In addition, striking at an angle to the target surface increased the pressure created. As a result, with a slashing blow, a saber causes more serious damage than a sword or broadsword of the same mass. An increase in curvature leads to an increase in cutting ability, but at the same time to a weakening of chopping properties.

European sabers typically had a slight curve to the blade to allow forward cuts, a relatively heavy weight, and a closed guard to provide a strong but uniform grip.

Notes

- Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary

- Marek Stachowski. The origin of the European word for sabre. Krakow, 2004.

- A. V. Komar, O. V. Suhobokov “Armament and military affairs of the Khazar Kaganate” (Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

- V. V. Gorbunov. “Military affairs of the medieval population of Altai (III-XIV centuries AD)”

- Golubev A. M., Golubeva I. V.

Single-edged weapon with a long blade of nomads of the 7th-8th centuries Template: Ref-lang = Single-edge weapon with a long blade of nomads of the 7th-8th centuries //

Archeology

. - 2012. - V. 4. - P. 42-54. - ↑ 6,06,16,2 Kirpichnikov A.N., “Old Russian weapons”, 1971.

- ↑ 7.07.1 A. N. Kirpichnikov, V. P. Kovalenko. “Ornamented and signed saber blades of the early Middle Ages (based on finds in Russia, Ukraine and Tatarstan).” 1993.

- Kirpichnikov A. N., “Military affairs in Rus' in the XIII-XV centuries.”

- K. S. Nosov. "Samurai Armament" 2001.

- M. V. Gorelik. "Armies of the Mongol-Tatars X-XIV centuries."

- O. V. Dvurechensky. "Cold offensive weapons of the Moscow state (late 15th - early 17th centuries)."

- Wojciech Zablocki. Ciecia Prawdziwa Szabla.

- Saber, weapon // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: In 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional ones). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Polish offensive weapons. Yu. V. Kvitkovsky

- According to the scientific director of the Moscow Kremlin museums A. Levykin.

- Wendalen Beheim. "Encyclopedia of Weapons".

- ↑ 17,017.1 V. Shlaifer, V. Dobryansky. "Saber - truths and legends."

- Viskovatov A.V., “Historical description of clothing and weapons of the Russian troops,” part 1.

- Alexey Isaev. Antisuvorov. Ten myths of World War II. [1]

- V.Volkov. "Wars and troops of the Moscow State."

Encyclopedic Dictionary (2009) SABER (Cold Weapon)

To the beginning of the dictionary

By first letter

0-9 AZ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P R S T U V

SABER (Cold Weapon)

SABER (melee weapon) - SABER (from Hungarian szabni - to cut), a chopping edged weapon.

It consists of a curved steel blade (see BLADE) with a blade on the convex side and a handle (hilt). It appeared in the East in the 6th-7th centuries, and later in Rus' and other European countries.