This term has other meanings, see Checker.

| Checker | |

| Caucasian saber with the “gurda” mark, scabbard and sword belt, from the collection of the Livrustkammaren Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. | |

| Type | checker |

| A country | Russia 1] |

| Service history | |

| Adopted | 1834 |

| In service | Caucasus region Russian Empire Russia |

| Wars and conflicts | Caucasian War Crimean War Russian-Turkish War 1877-1878 First World War Russian Civil War Second World War |

| Production history | |

| Options | Caucasian saber Cossack saber dragoon saber artillery saber[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Weight, kg | 1[3]—1.5[4] |

| Length, mm | 890[5]—1050[6] |

| Blade length, mm | 720[1]—880[7] |

| Blade type | single blade, curved |

| Hilt type | open closed |

| Media files on Wikimedia Commons | |

Checker

(from the Kabardian-Circassian seshkhue - long knife) [8] - a saber of the highlanders and Cossacks: quite wide, with a small blade, with a smooth and bare handle, in a leather sheath, on a narrow strap over the shoulder; carried in reverse, with the butt forward (blow in the sheath); checkers, according to the mark on them, are given special names: top, gurda, etc.[9] long-bladed cutting and piercing bladed weapon.

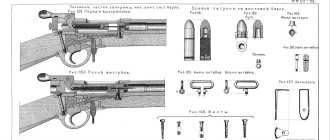

The blade is single-edged, slightly curved, double-edged at the combat end, less than one meter long (in Russia, various models of checkers were in service with a blade length of 81 to 88 cm, the original Circassian ones were even lighter and shorter). The hilt usually consists only of a handle with a curved, usually bifurcated head, without a crosspiece (guard), which is a characteristic feature of this type of weapon. The scabbard is wooden, covered in leather, with belt rings on the curved side. Two types of checkers are known: checkers with a bow, externally similar to sabers, but not such ( dragoon

type), and the more common checkers without a bow (

Caucasian

and

Asian

types).

Historical development

At first, the saber had the meaning of an inexpensive auxiliary weapon for a mounted warrior after the saber; the first examples date back to the 12th-13th centuries. There is an erroneous opinion that in written sources the word “checker” was first used by Giovanni de Luca in 1625[10], however, in the French text used by P. Yurchenko there is the word simeterre, which was translated by P. Yurchenko as “checker” without proper grounds , by analogy with the realities of the 19th century, in which this text was translated into Russian (the publication of P. Yurchenko’s translation is dated 1879). With the spread of firearms and the obsolescence of metal armor, the saber replaced the saber, first in the Caucasus and then in Russia, while the saber itself underwent significant changes: it became more massive and received a bend.

Checker, gift from the Presidium of the Soviet Union to Josip Broz (1944). Museum of Yugoslavia, Belgrade.

Having originally been borrowed from the Caucasian tribes by the Terek and Kuban Cossacks, in the 19th century the saber was adopted into service in the Russian army as the authorized type of bladed weapon of almost all cavalry units (by the beginning of the twentieth century, the saber remained a ceremonial weapon in the Guards Uhlan and Hussar regiments; in the 4th century in the cuirassier regiments of the Life Guards this was a broadsword), officers of all branches of the military, as well as the gendarmerie and police. The saber remained in the cavalry in this capacity until the middle of the 20th century, becoming the last melee weapon in history to have mass combat use (by the cavalry of the Red Army in the Great Patriotic War). In historical memory, the saber is noted primarily as a Cossack weapon, to this day remaining an integral part of the traditional culture of the Russian Cossacks and an element of the ancient Cossack costume.

Application of checkers

The checker is closer in structure and use to a knife than to a saber; various versions of the checker are fundamentally different from it in appearance: the absence of a guard (cross), the absence of a pronounced tip, much less curvature of the blade, a different balancing of the blade (for a classic checker, the balance point is located approximately thirty centimeters from the handle [ source not specified 784 days

]), - and the nature of its combat use: the saber is an offensive slashing weapon without the use of defensive tactics and sophisticated techniques of professional saber fencing.[11] The sword delivers powerful slashing blows, which are difficult to cover or dodge. Often a checker was intended for one sudden powerful blow, which often immediately decided the outcome of the fight. It is extremely problematic to deliver piercing blows with a saber due to the balancing features. The nature of the combat use also determines the method of attaching the sheath of the checker (on one or two rings) to the belt (to the waist or shoulder): with the blade up, since to perform a chopping blow from top to bottom, it is easier to quickly remove the checker from the sheath from this position. Another advantage of the checker was its relative cheapness, in contrast to the saber, which made it possible to make this weapon widespread. This was also facilitated by the ease of using checkers in battle. The usual technique of wielding a saber consisted of a good knowledge of a couple of simple but effective blows, which was very convenient for quickly training new recruits.[12] For example, the Red Army cavalry drill manual (248 pages) specifies only three blows (to the right, down to the right and down to the left) and four thrusts (half turn to the right, half turn to the left, down to the right and down to the left).

Production

Often the blades of Scottish broadswords were remade from outdated or out of order two-handed claymores of the 16th-17th centuries. High-quality blades were mainly imported from Europe (mainly from Italy or Germany), and Scottish gunsmiths made basket-shaped guards locally, most often in Glasgow and Stirling (there are several distinct varieties of such guards). The most famous manufacturer of blades for this weapon is the Italian master Andrea Ferrara, whose name became a household name and served as a synonym for the quality of the broadsword.

.

Checkers in Russia

Orenburg Cossack with a saber

In Russia, the saber was adopted by all cavalry units, artillery servants and the officer corps. In 1881, under the leadership of Lieutenant General A.P. Gorlov, an armament reform was carried out with the aim of establishing a uniform model of edged weapons for all branches of the military. A Caucasian blade was taken as a model for the blade, “which in the East, in Asia Minor, between the Caucasian peoples and our local Cossacks there is highly famous as a weapon that has extraordinary advantages when cutting.” Cavalry, dragoon and infantry sabers, as well as cuirassier broadswords, were then replaced by uniform dragoon and Cossack sabers of the 1881 model. The dragoon saber had a blade with one fuller and a bow-shaped hilt. The blade of the officer's saber was 10 cm shorter than that of the dragoon, and had three fullers. Artillery servants' checkers were made according to the pattern and size of an officer's checker, but the blade had one fuller instead of three. The Cossack units were also armed with checkers of the 1881 model. They were distinguished by the shape of the handle, which was devoid of a bow. The blade had one fuller, and the sheath was made like an officer's one.

Along with checkers of the 1881 model, the Russian army had checkers of other types.

The Asian-style saber of 1834 (reapproved in 1903) had a solid black horn handle with a forked head. This saber replaced the cavalry sabers of the lower ranks of the Nizhny Novgorod Dragoon Regiment, and in 1858 it was assigned to the lower ranks of the Seversky Dragoon Regiment, formed in 1856. In 1881, Asian checkers of the 1834 model were replaced in the Nizhny Novgorod and Seversky Dragoon regiments with Cossack checkers of the 1881 model, but in 1889, a reverse replacement took place. In 1891, these checkers (without bayonet sockets on the legs) were assigned instead of Cossack checkers to sergeants of the Plastun battalions and local teams of the Kuban Cossack army. Subsequently, these checkers were adopted for general service instead of the dragoon ones: in 1901 - in the Tver Dragoon Regiment, in 1903 - in the Pereyaslav Dragoon Regiment and the corresponding marching squadrons of the 7th Reserve Cavalry Regiment, as well as in the Novorossiysk Dragoon Regiment.

An Asian-style officer's saber was worn in all uniforms by officers of the Novorossiysk, Pereyaslavl, Tver, Nizhny Novgorod and Seversky dragoon regiments; Caucasian reserve cavalry division; 1st squadron of the 2nd reserve cavalry regiment; 7th squadron of the 7th reserve cavalry regiment; Caucasian horse-mountain artillery division[13].

The handle of a Caucasian-style checker consisted of a lower tip, a handle stem, placed on the tail of the blade and made of buffalo horn, and an upper tip, mounted on the tail and held by a screw that passed through the upper tip and tail of the blade. The officer's saber of the Caucasian type was worn in all uniforms by all ranks of His Imperial Majesty's Own convoy, generals and officers of the Caucasian Cossack troops, the Dagestan regiment, the Ossetian division, adjutants and ranks of the Retinue, listed in the Caucasian Cossack troops, generals and officers of infantry, artillery and engineering units, located in the Caucasus[13].

The Cossack saber of the 1839 model had a handle forged with brass along the head and back, where the forging was connected to the lower ring. The saber of the Caucasian Cossack army (model 1904) had a handle consisting of two “cheeks” fastened with three rivets on copper washers; the blade together with the handle was sheathed up to the head.

At the end of the 19th century, the hilts of officers' swords and the heads of the handles of Cossack swords began to be decorated with ornaments of leaves, forming a wreath on the frontal part of the head of the handles, in which the royal monogram was placed. By the beginning of the First World War, Cossack sabers of the 1881 model became widespread throughout the cavalry.

The 1881 model saber consists of a handle and a blade. The handle, in turn, consists of a jib, belly, back, and heel. And the blade is made from the tip, the warhead of the blade, the butt, the blade. The handle must strictly fit the owner's palm. This makes it more likely that the blow will go in the desired plane. For short fingers, a narrow handle is preferable, for long fingers, a wide one.

The butt gives the blade strength and also distributes its weight correctly. From the center of the impact to the tip, the butt sharply becomes thinner.

Cossack saber model 1881

The tip can be used for stabbing.

After the October Revolution, checkers were adopted by the Red Army, except for the Caucasian national units, which still had national-style checkers. A dragoon-style saber was also adopted for the command staff.

Since 1919, the saber has been a premium edged weapon.

In 1927, a new model of the Cossack-style cavalry saber was adopted by the Red Army, not much different from the 1881 model saber. In 1940, a ceremonial saber was introduced for generals and artillery generals (replaced by a dagger in 1949).

Since 1968, it has been a ceremonial weapon - assistants at the Battle Banner are armed with sabers (assistants at the Naval Flag have broadswords), as well as officers appointed to the honor guard.

The production of checkers was stopped in the 1950s due to the disbandment of the cavalry units of the Soviet Army (later, until the spring of 1998, single copies were produced as honorary award weapons). In the spring of 1998, large-scale production of checkers was resumed for the Cossacks, only by the end of March 1998 1000 checkers were ordered[14]. In addition, checkers are produced for commercial sale.

Naval (boarding) broadsword[ | ]

Main article: Cutting broadsword

The naval broadsword has been used since the 16th century as a boarding weapon. A boarding broadsword is a long-bladed cutting-and-piercing weapon with a straight, wide blade without a fuller, having a one-sided or one-and-a-half sharpening. The handle is wooden or metal with a guard such as a bow, cross, or shield. Unlike combat broadswords, which had a metal or wooden sheath, the sheath for a boarding broadsword was usually leather. The length of the blade was up to 80 cm, width - about 4 cm[4].

Notes

- ↑ 12

Astvatsaturyan, 2004. - Kulinsky, 1994, p. 77.

- Kulinsky, 1994, p. 88.

- Kulinsky, 1994, p. 75.

- Kulinsky, 1994, p. 80.

- Kulinsky, 1994, p. 78.

- Kulinsky, 1994, p. 73.

- Checker // Military encyclopedic dictionary / Prev. Ch. ed. Commission S. F. Akhromeev. - M: Military Publishing House, 1986. - P. 814. - 150,000 copies.

- SHASHKA (Russian). Dictionary Online

. Retrieved July 6, 2020. - “Caucasian checker” (undefined)

(inaccessible link) (June 2, 2009). Retrieved June 2, 2009. Archived November 9, 2009. - Checkers - ready for battle!: How to chop

- Cutting with a Cossack saber. Myths and reality

- ↑ 12

Cossack saber - Sergei Borodin. Russian Cossacks haven’t picked up a saber for a long time // Kommersant, No. 51, March 25, 1998, p. 4

| Wiktionary has an entry for " checker " |

Replica Scottish broadsword

Replica Scottish broadsword

Length - 100.965 cm. Weight - 1.6 kg.

View

Replica Scottish broadsword

Length - 95.6 cm. Weight - 1.6 kg.

View

Replica Scottish broadsword from 1750

Length - 95 cm. Weight - 1.18 kg.

View

Replica Scottish broadsword from 1716

Length - 100.965 cm. Weight - 1.36 kg.

View

If you liked the article, then share it with like-minded people

Comments ()

Notes[ | ]

- "Sword". Military encyclopedic dictionary. Moscow, 1984.

- GOST R 51215-98. Cold steel: terms and definitions.

- ↑ 123

“History of Russian material culture”, L. V. Belovinsky. University book, 2003 - ↑ 123456

“Sabres, broadswords, checkers and weapons with a curved blade,” comp. Yu. Kolobaev - ↑ 12

“Broadsword” (inaccessible link), Megaencyclopedia of Cyril and Methodius - Gorelik M.V. Armies of the Mongol-Tatars X-XIV centuries. Martial art, equipment, weapons. — M., 2002 (Series “Uniforms of the armies of the world”)

- A. V. Komar, O. V. Suhobokov “Armament and military affairs of the Khazar Kaganate” (Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

- ↑ 123456

"Steel arms. Encyclopedic Dictionary”, V. N. Popenko. AST, Astrel, 2007 ISBN 978-5-17-027396-6 - Kulinsky A. N.

European edged weapons. - St. Petersburg: Atlant, 2003. - P. 81. - 552 p. — ISBN 5-901555-13-9. - ↑ 12

Sword, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron. St. Petersburg, 1890—1907 - Doriyan Aleksandrov Makar and explain, find from the treasure in Voznesenka they say: “Find broadswords and sabi sa krivani in the Bulgarian necropolises from the 5th-7th centuries in the Northern Black Sea region and in other places, and discover in Voznesenka a sample of exactly this. Tova se potvarzhdava somehow from the format to the wedge to the edge, and from the beginning to the development.”|

- I. A. Military tactics of the Volga Bulgars in the pre-Mongol period

- ↑ 12

“White (or cold) weapons”, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron. St. Petersburg, 1890—1907 - “Solovetsky Stavropegic Monastery”, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron. St. Petersburg, 1890—1907

- “In the hiding places of the Solovetsky Monastery”, Evgraf Konchin. Magazine "Around the World" No. 11 (2553), November 1986

- ↑ 123

“Encyclopedic Dictionary of Russian Life and History: XVIII-early XX centuries,” L. V. Belovinsky. Olma Media Group, 2003, ISBN 5224040086, 9785224040087 - “Cold weapons,” Dictionary of Natural Sciences. Glossary.ru

- “Broadsword” (inaccessible link) (inaccessible link from 06/14/2016 [1471 days]), Russian Humanitarian Encyclopedic Dictionary

Story

This weapon owes its appearance to severe necessity: it was inconvenient to wield a long blade in the cramped conditions of a ship. The pirates allegedly shortened the blade and successfully operated with a compact weapon. Perhaps someone did just that - but it is still logical to assume that the authors of the new product were professional military sailors.

The army and navy have always responded much more quickly to changes in battle conditions and to the progress of weapons that could be used in them with maximum effect. Therefore, it is more likely that the boarding saber appeared first in the arsenal of military sailors, and only then migrated to the pirates. By the way, this statement is also supported by the fact that most sabers found by archaeologists have a more or less uniform shape and blade width. Consequently, they were made according to a certain standard, and were not made from blades picked up anywhere.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=i9FQ3PlR8Tg

The first mention of this weapon dates back to the second half of the 17th century, and it successfully existed almost to the present day. This “survivability” of the boarding saber is explained by the fact that it was an ideal weapon for fighting in close quarters and did not need to be replaced. The wide blade left terrible wounds upon impact, which quickly became inflamed in the humid maritime climate. Given the level of development of medicine at that time, in most cases they led to death.

It is not surprising that this massive and heavy blade quickly gained popularity among sea robbers. Plus, it was very easy to learn how to use it. No touches, floss or other sophisticated fencing intricacies were required during boarding. Speed and pressure were needed, and the boarding saber fully corresponded to these qualities.

Center of gravity

Well, the last thing Fedorov pays attention to is the center of gravity. Obviously, he writes, that in order to increase the force of the blow, the part of the blade with which the blow is struck must be heavier than all other parts of the saber, therefore, the center of gravity must be shifted as much as possible towards the tip

The part of the blade adjacent to the handle serves solely to transmit the force of the blow - in an ax this role is played by the ax handle. Therefore, it is not at all necessary to make it the same width and thickness as the rest of the blade. Nevertheless, European blades are made almost the same width along the entire length, sometimes even widening towards the hilt. Eastern curved sabers, on the contrary, widen towards the end, tapering towards the hilt. All this for one purpose - to give the working part of the blade maximum weight and lighten the rest.

By the way, with a piercing weapon the balance should be completely different: the closer the center of gravity is to the hilt, the more effective the thrust. A good example is French swords.

The center of gravity should not be confused with the center of impact, often indicated on eastern blades by a special notch on the butt; in the Russian saber of the 1881 model, the fullers end in this place. When the direction of impact passes through this point, the hand does not receive any shock.

Cossack sabers 15-18 centuries

The Persian saber shamshir, which was often made of Damascus or damask steel, was considered the best. Only rich Cossacks could afford such a saber, and even those most often took them in battle. The so-called “Adamashka” was also considered a very valuable saber. This word was used to describe all curved oriental sabers made of Damascus steel.

Apart from the shamshir, most of the Cossack sabers of that time were designed to deliver both chopping and piercing blows. Most saber handles were decorated with images of animals or birds, which served as a kind of amulet for the warrior.

Review of French sabers from the Napoleonic Wars

The era of the Napoleonic Wars was marked by radical reforms in military affairs. Naturally, it also affected the edged weapons of the French cavalry. Those sabers that were in service with the cavalry before the reform were too curved, which made it difficult to deliver piercing blows, which were indispensable in close combat.

As a result of innovations, the French saber received a new, less curved blade, which was perfectly adapted for both piercing and chopping blows. The point was shifted from the line of the butt to increase the piercing qualities. The blade itself was additionally sharpened near the tip on the butt side.

Weapons of the undersized dragoons

What should the ideal checker be like? Professional grunts - Cossacks and highlanders - have one answer to this question: of course, the famous Caucasian “top”. This is what Caucasian checkers were called in the 19th century because of the often found mark on them with the image of a wolf. However, this weapon is ideal specifically for professionals involved in dressage and practicing with a saber from early childhood for several hours a day. What the Cossacks and highlanders did with their blades was beyond the power of a combat soldier to repeat. They required a simple and reliable weapon, a kind of “Kalashnikov saber machine gun,” with which the soldiers could cut and stab tolerably well. Fedorov divided this problem into four subtasks: choose the correct curvature of the blade and handle attachment, check the position of the center of gravity and the weight of the blade.

1. The curvature of our blade, Fedorov wrote, exactly repeats the curvature of the famous Caucasian tops - ideally suited for both chopping and thrusting. The verdict was this: leave the curvature unchanged.

2. General Gorlov, in order to provide the saber of the 1881 model with better piercing properties, gave the handle a slope from the butt to the blade, directing the middle line of the handle to the tip. It became inconvenient to operate such a weapon. But the checkers of the Caucasian Cossack army of the 1904 model do not have such an inclination. It would be advisable to abandon the tilt in all checkers.

3. In our saber, the center of gravity is located 21 cm from the lower end of the bow, while in all samples of foreign edged weapons it is located at a distance of 9-13 cm from the hilt. If we take such blades in our hands and compare them with our saber, then it will immediately become obvious how much more convenient it is to act first, how light and free they are in the hand. Gorlov adopted the location of the center of gravity the same as in the Caucasian tops, thereby increasing the force of the blow. But let’s not forget, writes Fedorov, that it is easy for the mountaineers to operate with such weapons, since they are accustomed to wielding them from childhood. For combat dragoons with short service periods, this is unattainable. The conclusion is this: the center of gravity needs to be raised closer to the hilt

Moreover, with this arrangement, the tilt of the handle is no longer so important

4. The blade with the hilt of the Russian saber weighs 1.025 kg. Despite the fact that European models have a similar weight, Fedorov argues that it should be considered significant “for our undersized dragoons.” It is interesting that the saber originally designed by Gorlov had significantly less weight, but during mass production at the Zlatoust Arms Plant, the weight increased by almost 400 g, since the plant could not cope with the quality requirements for blades and sheaths. Therefore, it is necessary to return to the original weight characteristics.