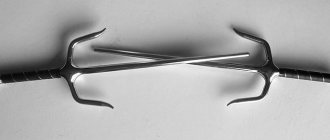

Some weapons work more effectively than others. Of course, weapons in themselves can hardly be called humane, but there are developments that, by general agreement, are especially dangerous and cause such terrible suffering that it is better not to use them. Thus, chemical and bacteriological weapons were prohibited. There has been a campaign to ban anti-personnel mines for many years. In the old days, the shadowy weapons genius also produced terrible things. They also tried to ban them, and to denigrate and punish the owners. One such achievement of blacksmithing was the flamberge, a sword with a wavy blade.

Soldiers of fortune with big blades

The name flamberge comes from the Old German “flamme” - flame. The blade of the sword really looks like a writhing tongue of flame. It was the Germans who were the first to widely use this type of sword. He was especially loved by the mercenary infantry - the Landsknechts. Almost immediately, the fashion was adopted by their Italian colleagues - condottieri. Fate more than once brought these soldiers of fortune to the battlefield, and each side actively used flamberges. This weapon had several advantages, for which it was highly valued by its owners and hated by its opponents.

As Richard Burton reports in The Book of Swords, the flamberge, firstly, could pierce armor more successfully than straight blades of similar mass. It's all about the shape of the blade. At the moment of collision with the armor, the energy of the impact was transferred to a small area, thus increasing the penetration ability. Secondly, the wavy blade caused terrible, non-healing wounds. A slight movement was enough for several parallel cuts to appear in the wound, as if left by a saw. Considering the level of medieval medicine, inflammation almost always turned into gangrene. The puncture wounds from the flamberge were especially terrible.

In addition, the wavy sharpening made it possible to cause significant damage to the enemy with a movement that had not previously been used in combat. After the blow, as soon as the sword was pulled towards itself, its “teeth” began to saw through everything that came along the way. This worked great against poorly equipped infantry.

That is why mercenary soldiers, who often fought for money rather than for an idea, really did not like opponents with flamberges. Even a small wound could put an end to one’s “career” and life. The owners of such swords were not taken prisoner, but were executed on the spot, sometimes subjecting them to terrible torture.

At the same time, owning a flamberge was very prestigious. This sword was more expensive than usual due to the difficulty of production; only experienced, accomplished condottieri and landsknechts could afford it. In addition, the owner of the sword seemed to publicly declare that he despises death and does not intend to surrender. Such a reputation was worth a lot in the market for mercenary troops.

Rorby swords – curved swords from the Bronze Age

In the materials published by VO, quite a lot of attention was paid to the history of bronze weapons, and this is not accidental. After all, in the history of mankind there was a whole Bronze Age, and this was the era of the first, in fact, globalization in the history of mankind, when people did not yet have writing, but... but they traded with each other over vast distances, which means they knew about each other . In Moldova, jade from the Sayan Mountains was found in the Borodino Treasure, although the distance between these points on the map is enormous. Is tin necessary for smelting bronze? Its deposits are quite rare, which means that it was traded many, many kilometers from the place of its extraction. It is not for nothing that the earliest bronzes contain arsenic and silver as alloys. Well, there wasn’t enough tin, so everything that was at hand was used! However, there was one of the readers who stated that bronze is an alloy of copper with... aluminum (!), but let’s leave such a bold statement on the conscience of its author (and Google will help him!), and we ourselves will pay attention to something else, namely - interesting evolution of the bronze blade.

Here they are - unique swords from Rorby.

I have already written here that the first swords in Europe were long “rapiers” for fencing with blades without hilts. Knives and daggers were made in a similar way: only the blade itself was cast, which expanded at the back, where there were holes for rivets: 2, 3, 4, 5, etc. A cut was made in the wooden handle, into which the blade was inserted and then secured with rivets.

Remake of a bronze knife from the Early Bronze Age. Apparently, valuable bronze was saved in this way, since archaeologists found many treasures with defective castings, scrap and individual pieces of metal - that is, they hid everything that had at least some value.

Then there was more metal. But the inertia of people’s thinking was such that daggers, for example, continued to be cast entirely in the form of old models with separate wooden handles. Moreover, they also reproduced the expansion of the rear part of the blade, which for the most part was completely unnecessary, and the rivets were even more unnecessary, since now they no longer held anything together and served only a decorative function.

A lot of bronze swords and daggers are found, which indicates the wide distribution of such products. And the showcase in the National Museum of Denmark is the best proof of this.

However, not only swords and daggers were the weapons of the Bronze Age people who lived in Denmark at that time. Look how many bronze axes are on display in this display case!

However, there were also transitional samples. They had a handle cast separately, a blade separately, and then all this was joined together with rivets. But such daggers and swords were characteristic of the early Bronze Age. People quickly realized that why rivet when you can cast. But, apparently, due to tradition, they could not refuse rivets at the junction of the blade with the handle.

A very beautiful dagger with a stacked handle (so this is where the tradition of stacked handles on prisoners’ knives comes from?!) and a blade riveted to it.

An amazingly beautiful and perfect solid bronze dagger from a private collection. Notice how simple and aesthetic it is at the same time. There is nothing superfluous in it, and at the same time, thin lines on the blade, massive rivets and a very simple handle create the impression of absolute completeness. As they say, there is nothing to add to it and nothing to subtract from it. Well, its form is also traditional and serves as the best proof of the inertia of human consciousness.

Of course, it helps archaeologists greatly that Bronze Age people were pagans and buried their dead with rich posthumous gifts. This is where bronze was not spared. However, valuable products of ancient gunsmiths are found not only in graves...

In the swamps of Denmark, not only bronze daggers are found, but also stone ones, that is, there was a Stone Age there, just like in other places, but then it was replaced by the “age of metals.”

And it so happened that in 1952, the Dane Thorvald Nielsen was digging a dredging ditch in a small swamp in the town of Rorby in the western part of Zealand. And it was there that he found an ornamented curved sword made of bronze, which was stuck in the turf. The sword clearly belonged to the early Bronze Age, around 1600 BC, and was the first such discovery in Denmark. By the way, notice how similar both it and the dagger in the above photo of the hilt are, which suggests that this form of pommel was widespread. The sword was transferred as an exhibit to the National Museum in Copenhagen, but the story of the curved sword did not end there. In 1957, while another Dane named Thorvald Jensen was digging for potatoes in roughly the same area, he discovered another such sword. The second curved sword was decorated like the first, but it also had an image of a ship on it. This turned out to be the oldest image of a ship in Denmark!

For an archaeologist, a gift of fate is not an excavated ancient mound. As a rule, this is someone’s burial, and usually a Bronze Age burial. And here they and Denmark were very lucky. About 86,000 prehistoric mounds have been discovered on its territory, of which about 20,000, according to experts, belong to the Bronze Age. Well, they are found everywhere on the territory of modern Denmark, which suggests that in the past it was densely populated.

But besides mounds, there are also swamps in Denmark. And so they became a real treasure trove for archaeologists. And what is not found in them, for example, among the most interesting “swamp finds” are... bronze shields that were made in central Europe in the period 1100 - 700. BC. Such bronze shields were known from Italy in the south to Sweden in the north, from Spain and Ireland in the west to Hungary in the east. It can be considered proven that shields made of such thin metal could not have had a military purpose. But for ritual purposes - as much as you like. Such shields were considered solar symbols and were closely associated with the veneration of gods and forces of nature. In Scandinavian rock art, designs of round shields can be seen in connection with ritual dances, so their cultic purpose is undeniable. But how were they found? This happened back in 1920, when two workers came to the editor of a local newspaper, Jensen, and brought two bronze shields that they found in the Sörup Moze swamp during the development of a peat bog. The largest shield was badly damaged by a blow from a shovel. The find was immediately reported to the National Museum, which began excavations. The workers reported that the shields were located vertically in the swamp at a short distance from each other. Archaeologists found this place, but there was nothing else there.

While mining peat in a small bog at Svenstrup in Himmerland in July 1948, Christian Jørgensen made another fantastic discovery. It was a beautiful bronze shield from the Late Bronze Age. He donated the shield to the museum, and received a good reward for it - enough money to pay for a new roof for his farm.

Experts immediately noticed that these shields were made of a very thin bronze sheet. Experiments with copies of these shields have shown that they are completely useless in battle. Their thickness allows them to pierce the metal anywhere, and if the shield is struck with the same bronze sword, it falls almost in half. This suggests that these shields were used exclusively for ritual purposes, but that people still tried to save bronze. After all, a thicker bronze sheet requires less work than a thin one.

Here it is, this exquisite buckle.

And this is a Danish banknote, on which the Danes placed her image and, it should be noted that many Danish banknotes were previously decorated with images of archaeological finds in Denmark dating back to the Stone and Bronze Ages!

It should be noted that the ancient Danes (or whatever they called themselves at that time?) were foundry masters. For example, the National Museum in Copenhagen displays a belt plate dating back to 1400 BC, covered with delicate spiral patterns. It was found back in 1879, again in a peat bog in North Zealand. Moreover, the worker who found it gave his find to the owner, and he, not knowing the real price of it and the other “coppers,” threw them into the trash heap, where they were noticed by a policeman who happened to look in on him. So, the technology for making such a plate was very original: a spiral of gold wire was inserted into a wax model, from which a clay mold was made. Then it warmed up, the wax flowed out, and molten bronze was poured into it. Everything seems simple. But this plate was very thin, so it required real skill to fuse gold with bronze in this way.

"Horned" helmet from Vikse.

And then in Viks in Zealand, one of the workers dug up two almost identical horned helmets made of bronze, made using the “lost shape” method. They were decorated with umbons, eyes, beaks and were made at the beginning of the first millennium BC. And again, these could not be helmets for combat. They were used in religious ceremonies, and then simply drowned in a swamp as a sacrifice to deities unknown to us. It is interesting that one of the helmets was placed on a preserved wooden tray, which, by the way, is not surprising, since peat has excellent preservative properties.

Mummies of women from Skrudstrupf. As you can see, thanks to the peat they were well preserved.

Both helmets from Vikse and accompanying finds.

True, it is not entirely clear where these “Vixe helmets” were made. Perhaps in the place where they were found, or perhaps it was in Central Europe or Northern Germany. In any case, numerous rock paintings of people wearing horned helmets, especially from western Sweden, indicate that the cult of the “horned man” was very popular here. Well, the “life path” of the objects of this cult ended again... in the swamp!

Lurs were also thrown there - huge pipes cast from bronze in the form of bull horns (c. 1000 BC), of which 39 were found in Denmark. Moreover, they are found only in swamps! That is, they were first made, using valuable bronze, then they were blown for some time, and then, together with shields, helmets and beautiful belt buckles, they were thrown into the swamp, and always in pairs.

"Lur of Brudevalte." This is what the “pipe” looked like, and it was... solid!

But here is a whole showcase of them!

Here you can clearly see all the detail on one of these swords. This is clearly a ritual object, and quite massive. And here the question is - what did he depict? After all, this is clearly a sword, but it is also obvious that one cannot fight with such swords. Then why was he given this particular form?

But let's return to the swords from Rorby. Their form is unique in that... they were not originally made for combat. After all, a sword without a point and without a sharpened blade can hardly be considered a combat sword. However, they did not save bronze on them, unlike shields. That is, the mercy of the ancestors or “swamp gods” was more important for the ancient inhabitants of Denmark than the price of metal, or they had it in abundance!

Former copper mine in Cyprus. Copper was mined here, and it was from here that all of Europe was supplied with this metal. But tin was mined in the British Isles, which the ancients called the Tin Isles. And maybe that’s why in Denmark, which lay on the route of ancient metal trade routes, there was so much bronze that products made from it were not only placed in the graves of the dead, but also thrown into the swamps of the gods?

Anathema for the sword

During the thirty-year war for power in the Holy Roman Empire and dominance in Europe (1618 -1648), mercenary troops played a special role. The main striking force in those days was the heavy cavalry, consisting of the clan nobility. In the eyes of the nobles, the infantry was just a bunch of rabble. But suddenly the infantry began to win victory after victory, and strategic advantage passed to whoever could pay the mercenaries the most. Often these were not noble, but wealthy representatives of the trading class.

Trying to turn public opinion against the new political force, the nobility enlisted the support of the church. Entire cities and mercenary armies were anathematized. She cursed the church and the flamberge sword as a creature of hell, which was greatly facilitated by the shape of the blade. History has not preserved exact data under which particular Pope this happened. But it is known that several centuries earlier, Pope Innocent II anathematized another weapon, equalizing the rights of the commoner and the knight. Then we were talking about a crossbow, the arrow of which pierced the powerful armor of a noble horseman.

However, the ideological war had little influence on the real war. No one was going to write off effective crossbows, and then flamberges swords because of the censure of the church. Later, firearms began to replace them almost simultaneously from the historical scene.

Now flamberges remain only in the form of ceremonial attributes. By the way, despite the bloody past, the Swiss Guard guarding the residence of the Pope in the Vatican is armed with such swords.

Main advantages

As already mentioned, the main advantage of the new weapon was the ability to cut through medium and even heavy armor. The main one, but not the only one.

Experienced fighters, having struck, tore the sword out of the enemy’s body with a “pull” - a sharp cutting edge with a wavy surface acted like a saw, cutting muscles. Some blacksmiths even deliberately spread the teeth slightly apart to increase the severity of the wounds inflicted by the weapon.

It was also very effective when delivering stabbing blows. The tip was not only carefully sharpened, but also did not have a wavy surface, and therefore, due to its large weight, it penetrated armor relatively easily. And then the irregularities of the blade came into play. As a result, the wounds practically did not heal. Even a relatively small wound (in the arm, leg, or tangentially in the chest) turned out to be extremely severe - pieces of meat were simply torn out of the body.

Finally, the flamberge sword turned out to be very convenient in defense. By exposing the blade to the enemy's blow, the warrior did not receive a crushing shock - the blow was extinguished gradually, rolling down the uneven surfaces of the sword. As a result, it became much easier to recover and counterattack the enemy.

Fencing schools

The ability to do without shields immediately gave rise to a whole herbarium of interesting fencing techniques.

We learn about them from “fencing books” - fencing manuals that were left to us by the great masters of the past - Johann Lichtenauer, Hans Talhoffer and others.

By the way. These two drawings were made by the same person. His name was Albrecht Durer - he was not only an excellent artist, but also a mathematician, a theorist of fortress defense and, of course, a fighter. His textbook on fencing and wrestling is considered a classic.

However, fencing schools should not be confused with military training. The fact is that fencing from treatises is of little use in war.

Basically, fencing books are textbooks on how to win a legal duel (whoever survives is right). However, at the knightly tournament, this knowledge was also very useful.

Some fencing books, written specifically for noble clients, are devoted to combat and fighting in armor using “noble” types of weapons. Some of them even depict the authors' cunning inventions, such as a shooting axe.

Another thing is war. The soldiers were taught to maintain formation and destroy those standing in the same formation opposite. The author does not recall any treatises on this topic.

Attitude towards owners

Many sources that describe Flamberge swords also mention the people who owned them.

Often these were Landsknechts, or Doppelsoldners. The last term can be literally translated as “double soldiers.” Why? It's simple. Because they always received double salary. True, every coin spent was justified.

To begin with, mercenaries (and soldiers of the regular army almost never used flamberges), armed with these terrible weapons, were always placed in the first line before the battle. That is, the main blow fell on them. They did this not in order to get rid of the mercenaries and not pay them after the battle. Simply working with a long flamberge while in the midst of allies was very problematic and completely unproductive. But chopping long spears and crushing the enemy’s armor and helmets with a good swing is just that. Since the two-handed flamberge sword had a very large weight (for comparison, an ordinary bastard sword rarely weighed more than 2 kilograms), it easily cut through thick shafts. Of course, the mortality rate was simply enormous. Such a risk had to be paid well.

However, the owners of the flamberges were fiercely hated by both enemies and allies. Simply because the swords caused so-called vile wounds - non-healing ones.

Therefore, mostly warriors captured with such weapons were hanged right on the spot. It is not surprising that such people have gained the reputation of daredevils who are not afraid of anything or anyone.

Was there poison?

Quite often you can hear legends that Landsknechts specially smeared the blade of their flamberges with poison in order, albeit not immediately, but certainly to kill the enemy.

However, no historical evidence of this has been found. The legend has a completely logical origin.

When a non-lethal wound was inflicted with a flamberge, the blade tore the flesh, damaging cells and blood vessels. Of course, local doctors did not use any antibiotics; the wound was not cleaned of dirt and tissue and skin from the armor that had gotten into it; at best, they simply wrapped it with a clean cloth. As a result, this led to gangrene. A man whose wound simply began to rot would die in terrible agony. This gave rise to the legend of poison applied to the blade.

Existing disadvantages

Any weapon, while gaining an advantage, also acquires certain disadvantages. Flamberge is no exception.

One of the main disadvantages is the complexity of manufacturing. It was much easier to forge a smooth sword than a flaming one. Therefore, only people who earned a living from it for a luxurious, albeit not always long, life could afford such a purchase - we’ll tell you about them a little later. Sometimes cheaper analogues were made - the blade of an ordinary two-handed sword was sharpened so that waves appeared on it.

Due to the wave-like shape, the strength seriously suffered - with a strong blow, the blade could simply break. This happened extremely rarely, but almost always resulted in the death of the owner.

Unlike classic swords, which were stamped in Europe in the thousands and tens of thousands, flamberges were produced individually and for a specific owner. This not only further increased the cost, but also complicated the creation process - it was necessary to select the appropriate steel, shape, balancing, and method of hardening the metal.