German gun for the Russian hunter

photo: Fotolia.com

Of course, you shouldn’t compare guns of the highest quality from English and German craftsmen; here the priority, of course, is on the side of the island gunsmiths. But as it is now customary to evaluate a product based on the price-quality ratio, there are no equals to German hunting weapons either among the British, or among the Belgians, or among the French, not to mention Russian manufacturers. Currently, the Italians are trying to compete with the Germans in the manufacture of affordable classic guns, which fully benefits the hunter who loves a double-barreled gun, where the magic of handcraft is still present, and not the practicality of a mechanical product.

There are legends about the popularity of German hunting weapons among Russian hunters. Rarely did any of the hereditary hunters not inherit: a “Sauer” of ordinary work - with a hawk or stork (heron), a trophy one (from the Hitler period) - with an eagle, as well as its higher quality manufacture - with the mark “guy with a club”. Some were lucky enough to inherit more expensive guns that did not have the above trademarks of Sauer's run-of-the-mill products, the "Germans" with full locks, Dutch pinwheels, often straight English stocks and all the bells and whistles associated with a classic gun that was superior in every way.

I had a lot of smoothbore "Germans". This is a vintage hammer with Damascus barrels and a Lancaster bolt; pre-war Sauer double-barreled shotgun of the Anson-Deeley system with a safety on the side, behind the block at the cheek of the stock; excellent, made in the English style, with the finest mesh cut on the neck of the stock and on the Greyfeld push-button forend; two later horizontals with Dutch locks, one of which had three pairs of barrels; already practically modern: “Merkel-201”, “Merkel-203” (had barrels of 12 and 20 calibers) and “Merkel-303” - all three Zulev models of “Merkels” were already produced in the GDR. All of them, regardless of the year of manufacture, the locking system and the grade of steel on the barrels, had one thing in common: like other “Germans” that passed through my hands over many years of work at the stand, they had excellent shot fire, despite the far from ideal condition of the tubes trunks.

It should be noted that the Germans, for the same price as the Belgians and the British, “lick” their guns so much that outwardly their Sauer, Merkel or Bühag seem much richer. And the fit of expensive German guns deserves kind words. Once I had to change the bolt lever spring on the Merkel-303 ET bench.

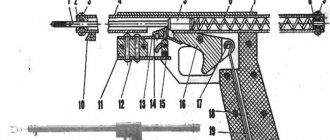

Anyone who has disassembled domestic MCs (the highest quality domestic TsKIB guns) knows how much work it takes to unscrew the screws. And on the Merkel, with a simple screwdriver, you can easily perform all operations without effort. The main screws on this model are locked small, and each one takes its place absolutely precisely, without the slightest hint of over- or under-twisting.

But what really captivates German guns is their amazing adaptability and balance. Their horizontal guns with a pistol stock and a cheekpiece on the butt fit perfectly into the shoulder without any adjustment, the shooter’s head is comfortable on the ridge of moderate width, the front sight is located exactly in the middle of the sighting bar. How German gunsmiths manage to do this is simply amazing.

The same can be said about hunting verticals. The bench models of Merkel and Zimson have stocks with a very large supply of wood for a strictly individual fit (but this is already a big sport that has nothing to do with hunting shooting).

Since we will next talk about shotguns with vertical barrels, let me dwell in more detail on this brand of German smoothbore shotgun. Any Merkel with a vertical barrel arrangement has an upper double locking - a Kersten lock, popularly called a “double Greener”, but not always a lower Perde locking frame, which does not generally affect the reliability of locking smoothbore guns.

| photo: Fotolia.com |

All “sides” have an original split forend, the upper part of which is secured with screws to the side rails of the barrels (today, this design has been preserved only on the most prestigious model 303 and its modifications and “Merkel 2003”). Almost always the forend latch is lever (rarely there may be a button).

The “Germans” use a pistol stock much more often than the English one, and the wood never hangs over the stock, giving the gun an expensive and noble look. But most German stocks have one drawback: the upper shank of the stock, which has a pointed end, can cause cracks to form over time. If there is a hint of warping in the wood around the shank, you should trim the wood until there is a tiny gap in front of the sharp end of the shank.

GED guns, of which probably more were imported into the USSR than remained in Germany, had a 70 mm chamber (modern German models have a 76 mm chamber and an additional zero in the numbering of the gun brand, for example, “203” became “2003”, and “ Merkel-303" remained with the same name).

The most expensive 303rd model had an impact-type ejector, and the second most expensive, 203rd, had an ejector mechanism similar to the IZH-27E ejectors, with spring-loaded ejectors. However, the design of the ejection device was not strictly related to the model of the gun (except for the 303rd).

“Merkel-303” and “Merkel-203” had locks on the “boards” and were declared by the company as locks of the “Holland-Holland” system. In my opinion, there is some overkill here: the mainspring is not at all Dutch, it is short, and is located behind the trigger, and not below and in front. However, the turntables on the 203rd are just like those of the “Englishman”, and on the 303rd they are of a special design, disguised in a side lock, which makes it easy to replace the spring, clean and lubricate the trigger - everything is like Holland’s.

A certain disadvantage of the Merkel USM is the relative fragility of the mainsprings, and the plus is their high speed of operation. If in the hunting version there is no need to worry about spring breakage, then on the bench, with intensive use of the gun, replacing the spring is a common thing. That is why the main bench “merkels” are models “303” and “203”, where replacing the spring will take a few seconds, while for other “merkels” this operation will require a special tool and will take a lot of time.

The main choke options: choke/full choke, 1/4 choke and 3/4 choke or cylinder/choke indicate their size. There are long, smooth narrowings that give a more uniform distribution of shot across the shot area. Short, steep chokes are made that are capable of “driving” the shot to the center of the scree; they are long-range, but “picky,” that is, they cannot tolerate hard wads.

Perhaps someone will disagree with me, but I dare to say that a gun with constant choke constrictions is more reliable. And if we take into account the range of offered cartridges of various loadings, which allows us to get a bunch of fire, a wide scree or moderate accuracy from one barrel, then for me it’s better to have the necessary set of ammunition than to twist the choke tubes for fear of losing or forgetting the key to them.

And any decent guns, unlike the relatively cheap “Italians” and other manufacturers of gun consumer goods, are made exclusively with constant choke constrictions. Although, sadly, after the unification of Germany, the quality of the guns from Suhl decreased somewhat, they somehow became rougher and more “soulless”.

Yuri Konstantinov February 1, 2014 at 00:00

Merkel and the Fourth Reich

Igor Shishkin, February 25, 2020, 00:01 — REGNUM Part one: Merkel can do what neither Wilhelm II nor Hitler could do

In building the Fourth Reich, Angela Merkel relied on maximally strengthening cooperation with the United States. This gives Germany a unique chance, without the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and a war on two fronts, to create a Fourth Reich, incomparable in power to the Second and Third, capable of, with a successful combination of circumstances, in the midst of a future confrontation between America and China, seizing leadership from the Anglo-Saxons. To do what neither Wilhelm II nor Hitler could do.

I.

The year that has passed since the coup in Kyiv has radically changed Russian-German relations. Over the past decades, their “special” character has been taken for granted by many in Russia. This “specialness” was also believed and at the same time feared in panic in Eastern Europe. Each Russian-German agreement caused a cry there about a new Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, about another attempt by the Moscow-Berlin tandem to divide Europe. Suffice it to recall how the current Chairman of the Polish Sejm, Radoslaw Sikorski, saw in the agreement on the construction of the Nord Stream gas pipeline an “ominous pact” and a direct threat to the existence of the Polish state. Throughout the first months of the Ukrainian crisis, journalists and bloggers rushed to call Angela Merkel “Frau Ribbentrop” after every conversation she had with Putin.

How strong such fears were is evidenced by the fact that she even had to time her meeting with Petro Poroshenko in Kyiv to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the pact and make a special statement. “My presence here shows that everything has changed. Germany does not want to provoke a new political disaster” (Angela Merkel, German Chancellor). However, Merkel’s words did not shake the belief in the “specialness” of Russian-German relations among some and did not dispel fears of this “specialness” among others. Even in the fall of 2014, there were many publications in the Russian press about Germany, on the one hand, full of sympathy (the policy of sanctions against Russia “obviously” contradicts its national interests), on the other hand, hope (who else, besides Germany, in Europe can, in the name of own interests to stop the conflict provoked by America in Ukraine?):

“There is no doubt that it is the leader of the EU, Germany, who will very soon become at the forefront of the process of returning normal relations between Russia and the European Union” (Boris Yakemenko, historian, member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation, 09/25/14);

“While Berlin is slowly trying to find a foothold to get out of the “Ukrainian swamp,” Washington is doing everything possible to make the Europeans plunge even deeper into it” (Boris Kagarlitsky, economist, 10/24/2014).

However, by the end of the year it became quite obvious that not a trace remained of the “special” Russian-German relations. Germany, which even at the height of the Cold War, despite all US pressure, developed economic ties with the Soviet Union, has now become the most active and consistent pursuer of the sanctions policy among EU members. Regardless of any damage to your own economy. “Germany acts as a leader when it comes to sanctions against Russia... Its energy, mechanical engineering and east-oriented companies have a powerful lobby, including in Merkel’s own party. However, she was able to set everyone on the path to using sanctions” (Timothy Garton Ash, The Guardian, UK).

Therefore, it is not surprising that the influential British publication The Times, summing up the results of 2014, named Angela Merkel “Person of the Year” for her “contribution to strengthening European security during the period of the revival of Russian aggression in Eastern Europe.” The role of Angela Merkel was no less highly appreciated in the Russian liberal community. “Angela Merkel played a decisive role in opposing Putin’s aggression against Ukraine and his broader concept of the so-called Russian World. She played a greater role than the clearly weaker politician Obama, and acted as the leader of the Western world” (Andrey Piontkovsky, political scientist, Russia).

No explanation has appeared recently for the reasons for the radical change in Germany's eastern policy, both in Russia and abroad. Starting with the most original ones. Including even these: “He annexed Crimea and sent his forces to Eastern Ukraine. But it was only when she became acquainted with his traditionalist views on gay rights that Angela Merkel was finally convinced that reconciliation with Vladimir Putin was impossible” (Bojan Panchevski, journalist, The Sunday Times). “Merkel cannot find a common language with authoritarian men who demonstrate how macho they are - these topless photos of Putin” (Dirk Kurbuweit, editor of Spiegel magazine, author of two books about Merkel).

What prevails, of course, is a much less exotic explanation - Germany still does not have full sovereignty and actually remains a country occupied by the United States, and its chancellors since 1949, as former German intelligence chief Komosa said, have been forced to sign a special “Act” upon taking office. Chancellor”, confirming vassal dependence on America: “Judging by the way the current German Chancellor A. Merkel behaves in connection with the events in Ukraine, it can be assumed that the “Chancellor Act” continues to be in force” (Valentin Katasonov, professor at MGIMO).

At the same time, the idea that the end of the “special” relationship with Germany was not the result of an objective divergence of interests of the two countries, manifested in the Ukrainian crisis, began to actively take root in Russian public opinion, but a consequence of the political choice of a particular German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, who was completely dependent on the Anglo-Saxons and acting contrary to the interests of its own country: “The fact that Merkel’s statements and the interests of Germany diverged does not raise any doubt in my mind” (Sergei Markov, political scientist); “Angela Merkel, supporting US sanctions against Russia, did a lot to ensure that Great Britain strengthened its influence in the European space, weakening Germany” (Alexei Mukhin, political scientist); “Mrs. Merkel in this case is the representative of the Anglo-Saxons in continental Europe. A sort of Anglo-American policeman. Under her, Germany for the first time began to take a pro-American and pro-British position, which has not happened since the time of Adenauer” (Dmitry Zhuravlev, General Director of the Institute of Regional Problems).

There are also references to the behests of Bismarck and the traditions of the “Eastern Policy” of Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, trampled upon by Angela Merkel to please her overseas masters: “Is there a portrait of Bismarck in the Merkel residence? If so, then she probably feels awkward under his piercing gaze" (Free Press, Bismarck's Shadow). However, are the respected denouncers of Merkel's policies wishful thinking?

II.

America’s interest in aggravating Russian-German relations is obvious, and they are not even trying to hide it overseas: “The United States should fear most of all the alliance between Russia and Germany” (J. Friedman, head of the Stratfor analytical center, USA, 2014).

Berlin's dependence on Washington is also obvious. Only from these evidences it does not at all follow that Angela Merkel is building a policy with Russia based not on German national interests, but solely to please the United States. Poland is much more dependent on Washington, and in addition on Berlin, but is its policy in the Ukrainian direction determined by this? Rather, it can be argued that it is precisely the vassalage of the “powers of this world” that allows it to realize its own aspirations in the “eastern lands.” Moreover, there is no reason to look for the root cause of the actions of Germany, currently the most influential political and economic player on the European field, depending on the United States.

“Angela Merkel, while more of a pragmatist than most other leaders, was hardly a friend of Russia... A simple question: which Ukraine would Germany prefer to see - pro-Western or allied with Moscow, which could again turn Russia into a European superpower. The answer is self-evident” (Dmitry Simes, president of the Center for National Interest, publisher of The National Interest magazine).

Just as dubious as ignoring Germany’s national interests are Merkel’s accusations of forgetting the behests of Bismarck, whose policies are usually presented almost as an example of “special” Russian-German relations. The point, of course, is not the quote from Bismarck that has been wandering from publication to publication lately about the need to tear Ukraine away from Russia. This, as they say now, is a fake. But the old way is fake. But even without these forgeries, we have no reason to see in Bismarck a “friend” of Russia. He expressed his attitude towards our country very clearly and clearly: “I cannot get rid of the thought that in the future, and perhaps even in the near future, Russia threatens the world, and, moreover, only

Russia" (Otto von Bismarck, first Reich Chancellor of the Second Reich) [the word “only” is emphasized by Bismarck - I.Sh.].

This position of Bismarck fully coincided with the position of Frederick the Great, who made no less a contribution to the creation of the German Empire: “Russia is a terrible power from which all of Europe will tremble in half a century. Descended from these Huns and Gepids, who crushed the Eastern Empire, the Russians can very soon attack the West” (Frederick the Great, King of Prussia). It should be especially emphasized that this was written at a time when Prussia was officially in a military alliance with Russia.

There is nothing surprising in such unanimity of the two great German politicians in relation to Russia. The Prussians, who played a leading role in the formation of the modern German state, were formed as a special branch of the German nation in the process of the “pressure to the East.” It can be said that their fate and history are inseparable from the Drang Nacht Osten. This is their ethnocultural dominant. Hence the completely understandable and understandable attitude towards the Russian nation, which put a limit to their “onslaught”, as a global, existential enemy.

Bismarck really bequeathed not to fight with Russia, which we are very fond of talking about, forgetting to add that behind this lay not the conviction in the strategic expediency of mutually beneficial good neighborly relations, but solely the understanding of the impossibility of “finally” solving the Russian question by military means: “We will, according to In my opinion, we will have greater success if we simply treat them as an existing constant danger... we will never be able to eliminate the very existence of this danger” (Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of the Second Reich).

At the same time, the “Iron Chancellor” did not at all call on the Germans to come to terms with the inevitability of coexistence with Russia. He proposed to wait until Russia itself collapses due to internal unrest, and then, without risk to ourselves, take advantage of the opened “window of opportunity” and fulfill Germany’s destiny - to promote the only correct civilization to the East: “By attacking today’s Russia, we will only strengthen its desire for unity; waiting... can lead to the fact that we will wait for its internal disintegration before it attacks us, and moreover, we can wait for this, the less we prevent it from sliding into a dead end through threats” (Otto von Bismarck, first Reich Chancellor of the Second Reich).

In this regard, the idea of the German politicians who started the war with Russia in 1914 as antipodes of Bismarck, deniers of his behests, is completely unfounded. They treated Russia in exactly the same way as he did: “Russia must be ruthlessly suppressed” (Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, Reich Chancellor of the Second Reich, 1914). But unlike Bismarck, they were sure that they could not wait any longer. They believed that there was no other way to solve the “Russian question”, which was fateful for the Germans, except to take advantage of the peak of the military-economic power of the Reich and the temporary weakness of Russia. In addition (as always), the “Englishwoman was crap”, creating confidence among the Germans that she would not enter the war: “Russia is getting stronger and stronger. It's turning into a nightmare... Now there are chances that everything will work out. By 1917, Germany will not have any... The Western powers will abandon Russia, the Entente will collapse, and Germany will emerge victorious" (Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, Reich Chancellor of the Second Reich, 1914).

It is significant that after the collapse of the Russian Empire, Germany, instead of transferring the liberated troops to the Western Front, rushed to capture and plunder to the East along the Ukraine-Crimea-Caucasus line. In full confidence that mastery of Russian resources is the main guarantee of victory in the world war. What the Anglo-Saxons had no doubt about then: “Germany, having taken control of the resources of Russia [in 1918, everyone considered Ukraine, Crimea and the Caucasus to be Russian territory], will become invincible” (David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister in 1916-1922. ).

During the Third Reich, everything was repeated with amazing accuracy: the confidence that without the destruction of Russia (then called the USSR) Germany had no future; that we can’t wait any longer - either now (while Russia is weak and the Reich is at the peak of its power), or never again; that without seizing the resources of Ukraine and the Caucasus it will not be possible to win in the West. One of the leading Soviet and Russian Germanists, Yuliy Kvitsinsky, very precisely defined the essence of German policy towards Russia: “Germany’s Eastern policy has always been a function of the power or weakness of Russia. Germany adapted to strong Russia and sometimes acted together with it; it attacked weak Russia and plundered it” (Juliy Kvitsinsky, USSR Ambassador to Germany, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR).

This formula fully fits not only the policy of Germany during the time of Bismarck, the First World War, the throw to the East in 1918 and the Great Patriotic War, but also during periods of mutually beneficial cooperation. The Treaty of Rapallo of 1922 still provides ample food for speculation about the special “spirit of Rapallo” in Russian-German relations. The treaty undoubtedly broke the diplomatic blockade of Soviet Russia from the West, but it was also Germany’s first equal treaty after its defeat in the world war. In those conditions, no one else except Russia wanted to cooperate with defeated Germany on equal terms. However, at the first opportunity, in order to improve relations with the Anglo-Saxons and the French, Germany exchanged the “spirit of Rapallo” for the “spirit of Locarno,” openly directed against Russia. There was also the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, according to which, in exchange for a guarantee of neutrality in the war for leadership in the Western community against Poland, France and Great Britain, Germany recognized the interests of the USSR in the post-imperial space. That did not prevent her, again, at the first opportunity, from breaking the pact and heading along the traditional route to the East.

III.

Yuliy Kvitsinsky’s formula is also true in relation to the “Eastern Policy” of Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, for forgetting the traditions of which Angela Merkel is most often accused. In the USSR, the Moscow Treaty with Germany of 1970 was never called anything other than “historical”. Until now, it is considered one of the greatest achievements of domestic diplomacy. Of course, he gave the green light to the policy of détente, West Germany finally recognized the post-war borders in Europe: “The Moscow Treaty became not only the legal basis for a radical improvement in Soviet-West German relations, but also largely contributed to a favorable change in the political climate in Europe, strengthening security and trust in the center of the European continent. He removed the most serious obstacle to ensuring lasting peace in Europe - the non-recognition of post-war borders by the former governments of the Federal Republic of Germany" (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, ON THE MOSCOW AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE USSR AND THE FRG, Information and reference material).

However, there is every reason to assert that the agreement reflected a change only in tactics, and not in strategy, in the “Eastern policy” of Germany. In reviving German statehood, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer, relied on the country's complete subordination to the United States, repentance for the Holocaust, and consent to Austrian independence. In this way, he sought, firstly, to restore German positions in the Western community, and secondly, using the power of the United States, to absorb the GDR and return the 1937 borders to Germany, including the Kaliningrad region and the East German lands that had been transferred to Poland. Hence the demonstrative course towards confrontation with the USSR and the stubborn non-recognition of post-war borders: “The result should have been the restoration of the positions lost by Germany in Central and Eastern Europe... It was a policy... relying on the West, to take revenge in the East for the lost World War II” (Juliy Kvitsinsky , USSR Ambassador to Germany, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR).

At the end of World War II, part of the German elite considered it necessary to capitulate to Western opponents in order to preserve the opportunity to continue the war in the east against the USSR. It can be said that Adenauer brought these ideas to life under new conditions after the defeat of the Third Reich. Adenauer achieved the first of his goals - defeated Germany became not only a full member of the West, but gradually became the economic leader of Europe. And in the 21st century, thanks to the course he charted, the issue of German control over European structures that were once created in order to keep the Germans in the power of the Anglo-Saxons is already on the agenda.

“Germany is increasingly trying to seize control of the European Union, which was largely created as an Anglo-Saxon project of control over Europe, and primarily over Germany itself. That is, the ambitions of Germany, which itself has not yet restored its own sovereignty, already extend to the entire continent. The Fourth Reich is not an invention of propagandists, but an inevitable consequence of the development of the German people if they free themselves from the Anglo-Saxon overseer" (Petr Akopov, publicist, Vzglyad newspaper).

Adenauer’s “Eastern” policy, unlike the “Western” one, suffered a complete collapse. The military power of the USSR was such that it was impossible to force it to leave East Germany. It was not possible, despite all the efforts of the German authorities, to provoke America and England into a war with the Soviet Union. It turned out that the course to restore Germany within the borders of 1937 was unpromising from a position of strength. We had to move from confrontation with the Soviet Union to cooperation. To carry out, starting with Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, a new Ostpolitik, which in Germany was called the “turn through cooperation.” Its starting point was the Moscow Treaty of 1970. It should be especially emphasized that Germany was able to radically change its policy towards the USSR - from confrontation to cooperation - at the very height of the Cold War, despite the open opposition of the United States. The Germans, when it came to their vital interests, were not hindered by either the American occupation forces or the Chancellor's Act.

The FRG had to pay for the new eastern policy by recognizing the GDR, the new borders of Poland and the Soviet Union. However, it gave West Germany leverage in the direction it wanted on the USSR and the opportunity to prepare the ground for the peaceful absorption of the GDR (Bonn forgot about the legal formalities associated with its recognition at the first opportunity): “Shifting the emphasis from violence to cooperation and openness, to human rights turned out to be more fruitful in a political and socio-economic sense than any of the military systems and technologies invented after 1945” (Valentin Falin, USSR Ambassador to Germany, head of the international department of the CPSU Central Committee).

The new Eastern policy was built in strict accordance with Bismarck's precepts - not to enter into direct confrontation with Russia, but to wait for its internal collapse and prepare for a breakthrough to the East. We didn’t have to wait long: “When the Berlin Wall collapsed, and then the Soviet Union itself, the Moscow Treaty of the USSR was of no use... The West German policy of revising the results of World War II triumphed” (Juliy Kvitsinsky, USSR Ambassador to Germany, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR).

However, we must not forget that Germany did not achieve a complete revision of the results of World War II then, and even now: only East Germany was able to be returned, the western border of Poland remained along the Oder and Neisse, and Koenigsberg is still Kaliningrad. The collapse of the Soviet Union did not automatically lead to a revision of the Brandt-Schmidt course in German eastern policy. It did not yet have the economic or military-political forces to rush to the East. First of all, Germany had to integrate the GDR and digest the Soviet legacy in the East (Dmitry Semushin, REGNUM news agency columnist).

In addition, the “special” relations with Russia, which reached their peak under Helmut Kohl and Gerhard Schröder, allowed Germany to take the extremely politically advantageous position of Russia’s curator in the European Union, which for some reason we considered the position of “Russia’s lawyer” in the EU: “Germany was the main defender of Russia’s interests in Europe” (Alexander Tevdoy-Burmuli, Associate Professor of the Department of European Integration at MGIMO (U) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, 11.27.14)

In economic terms, “special” relations created ideal opportunities for the “development” of the Russian market, the gradual transformation of Russia into a raw material appendage of Germany: “Germany has transformed its trade relations with Russia from the previous mutually beneficial ones into colonial ones: it exports high value-added industrial goods there, and imports gas, oil and raw materials" (James Petras, professor, USA).

Only by the mid-2000s, the creative combination of the course of Adenauer (in the western direction) and Brandt-Schmidt (in the eastern direction) created the conditions for German policy to reach a qualitatively new level. It was Angela Merkel, who headed the German government in 2005, who tried to convert economic leadership in the European Union into political leadership, to revive the German Reich created by Bismarck in a new guise, which made a radical change in Germany’s “Eastern policy” inevitable.

To be continued…