Musketeer with a musket. 17th century engraving

Babur's warriors with multuk muskets.

Mughal miniature of the 16th century. Musket

(from the French Mousquet, more likely from the German Muskete) - a type of ancient hand-held firearm. The specific meaning of this term may vary depending on the historical period and the characteristics of national terminology.

Story

Initially under musket

understood the heaviest type of hand-held weapon, intended mainly for hitting targets protected by armor. According to one version, the musket in this form originally appeared in the Spanish Empire around 1521, and already in the Battle of Pavia in 1525 they were used quite widely. The main reason for its appearance was that by the 16th century, even in the infantry, plate armor had become widespread, which did not always make its way out of lighter hand-held culverins and arquebuses (in Rus' - “arquebuses”). The armor itself also became stronger, so that arquebus bullets weighing 18-22 grams, fired from relatively short barrels, turned out to be ineffective when firing at an armored target. This required increasing the caliber to 22 or more millimeters, with a bullet weight of up to 50-55 grams. In addition, muskets owe their appearance to the invention of granular gunpowder, which radically facilitated the loading of long-barreled weapons and burned more completely and evenly, as well as to the improvement of technology, which made it possible to produce long, but relatively light barrels of better quality, including from Damascus steel.

The length of the musket barrel, usually faceted, could reach 65 calibers, that is, about 1400 mm, while the muzzle velocity of the bullet was 400-500 m/s, making it possible to defeat even a well-armored enemy at long distances - lead musket bullets they pierced steel cuirasses at a distance of up to 200 meters and could inflict wounds at a distance of up to 600 m. The musket had satisfactory accuracy at a distance of up to 150–200 steps, but could maintain lethal force at a distance of up to 400 steps[1].

Regarding the rate of fire of muskets, there is the following information: during the shooting in 1620, a shooter from the troops of Gustavus Adolphus fired 6 shots in 5 minutes, shooting for speed and accuracy. In Scotland in 1691, the following rate of fire record was achieved: a shooter fired 30 shots in 7 minutes[2].

According to tests conducted at the Graz Museum (where several surviving muskets of the 16th-17th centuries with matchlocks, flintlocks, and wheel locks were shot), the technical accuracy of the muskets made it possible to hit a target measuring 60 by 60 cm at a distance of 100 meters [3]. It is worth considering that at the time of ballistic tests the muskets were more than 300 years old, and different gunpowder charges were used, which could affect the accuracy of fire. Penetration tests were also carried out. From a distance of 30 meters, musket bullets pierced steel sheets up to 4 mm thick, or wooden blocks up to 20 cm thick. As you can see, muskets posed a threat not only to armored horsemen and pikemen, but also to infantry hiding behind light field fortifications or buildings.

Combat use

The musket of the 16th-17th centuries was very heavy (7-9 kg) and was essentially a semi-stationary weapon - it was usually fired from a rest in the form of a special stand, bipod, reed (the use of the latter option is not recognized by all researchers), the wall of a fortress or the sides of the ship. The only hand weapons that were larger and heavier than muskets were fortress guns, which were fired exclusively from a fork on the fortress wall or a special hook (hook). To reduce recoil, shooters sometimes put a leather pad on their right shoulder or wore special steel armor. In the 16th century, locks were made of wick or wheel locks; in the 17th century, they were sometimes flint locks, but most often wick locks. In Asia there were also analogues of the musket, such as the Central Asian multuk

(karamultuk).

A marksman in the army of the Great Mogul Akbar with a matchlock musket.

Mughal miniature 1585. The musket was reloaded on average for about one and a half to two minutes. True, already at the beginning of the 17th century there were virtuoso shooters who managed to fire several unaimed shots per minute, but in battle such shooting at speed was usually impractical and even dangerous due to the abundance and complexity of methods for loading a musket, which included about three dozen separate operations, each of which it was necessary to carry out with great care, constantly monitoring the smoldering wick located not far from the flammable gunpowder. However, the majority of musketeers neglected the statutory instructions and loaded the muskets as it was easier for them, as directly evidenced in the German-Russian regulations[4]. To increase reloading speed, many musketeers avoided the time-consuming operation of a ramrod. Instead, a charge of gunpowder was first poured into the barrel, followed by a bullet (usually several bullets were kept in the mouth). Then, by quickly striking the ground with the butt, the charge was further nailed down, and the musketeer was ready to fire. This kind of initiative among personnel has been preserved throughout modern times, as evidenced by some sources from the 18th and 19th centuries[5]. It was difficult to accurately measure the charge in battle, so special cartridge belts were invented, each of which contained a pre-measured amount of gunpowder per shot. They were usually hung on uniforms, and are clearly visible in some images of musketeers. Only at the end of the 17th century was a paper cartridge invented, which slightly increased the rate of fire - a soldier tore the shell of such a cartridge with his teeth, poured a small amount of gunpowder onto the seed shelf, and poured the rest of the gunpowder along with the bullet into the barrel and compacted it with a ramrod and wad.

Musketeer of Shah Abbas I. Miniature by Habib Mashadi. 1600

In practice, musketeers usually fired much less often than the rate of fire of their weapons allowed, in accordance with the situation on the battlefield and without wasting ammunition, since with such a rate of fire there was usually no chance of a second shot at the same target. Only when approaching the enemy or repelling an attack was the opportunity to fire as many volleys as possible in his direction appreciated. For example, in the Battle of Kissingen (1636), during 8 hours of battle, the musketeers fired only 7 volleys.

Musketeer. Colorized engraving from the album of Jacob de Gheyn II (1608).

But their volleys sometimes decided the outcome of the entire battle: killing a man-at-arms from 200 meters, even at a distance of 500-600 m, a bullet fired from a musket retained sufficient lethal force to inflict wounds, which, given the level of development of medicine at that time, were often fatal. Of course, in the latter case we are talking about random hits from “stray” bullets - in practice, the musketeers fired from a much shorter distance, usually within 300 steps (about the same 200 m). Contrary to popular belief, all muskets of the 16th-17th centuries had a rear sight and a front sight (in the 18th-19th centuries the rear sight was abolished and a slot in the breech screw was used instead). But most musketeers did not have sufficient fire training to realize the full capabilities of their weapons. For example, it was necessary to take a significant lead depending on the distance to the target. If the enemy was 100 steps away, then it was necessary to aim at the knees, otherwise the bullet would simply fly over his head. If the enemy was 300 steps away, then you had to aim above his head, otherwise the bullet would fall before his feet before reaching him. It would seem that the rules were simple, but most people forgot about them in the heat of battle.

If in Europe firearms completely replaced throwing weapons, then in the east bows and muskets “coexisted” until the end of the 17th century. For example, during the siege and assault of the Turkish fortress of Kyzy-Kermen, many Cossacks were wounded by arrows. According to the statistical sample, the majority of injuries were caused by bullets (36%), followed by injuries from arrows (31%)[6]. It is worth considering that the bullets caused more severe wounds.

Moving on to guns

Meanwhile, in the 17th century, the gradual withering away of armor, as well as a general change in the nature of combat operations (increased mobility, widespread use of artillery) and the principles of recruiting troops (a gradual transition to mass conscript armies) led to the fact that the size, weight and power of the musket over time began to be felt as clearly redundant. The appearance of light muskets is often associated with the innovations of the Swedish king and one of the great commanders of the 17th century, Gustav II Adolf. However, in fairness, it is worth noting that most of the innovations attributed to him are borrowed from the Netherlands. There, during the long war between the United Provinces and Spain, Stadtholder Moritz of Orange and his cousins John of Nassau-Siegen and Wilhelm-Ludwig of Nassau-Dillenburg fundamentally changed the military system, carrying out a military revolution. Thus, John of Nassau-Siegen wrote back in 1596 that without heavy muskets, soldiers would be able to move forward faster, it would be easier for them when retreating, and in a hurry they would be able to shoot without a bipod[7]. Already in February 1599, the weight of the musket was reduced by the Dutch regulations and amounted to approximately 6-6.5 kg [7] [8]. Now such muskets could be fired without a bipod if necessary, but this was still a rather difficult process. It is often claimed that it was the Swedish king who finally abolished the bipod in the 1630s, but records in the Swedish arsenals of that time indicate that he himself personally placed an order for the production of bipods for muskets from the Dutch entrepreneur Louis de Geer, who moved to Sweden, as early as 1631[ 8]. Moreover, their mass production continued even after the death of the king, until 1655[8], and bipods were officially abolished in Sweden only in the 1690s - much later than in most European countries[9].

Later, already in 1624, the Swedish king Gustav Adolf, by decree, ordered the production of new matchlock muskets, which had a barrel of 115-118 cm and a total length of about 156 cm. These muskets, which were produced until 1630 in Sweden, weighed approximately 6 kilograms, which indicates that they were still not entirely comfortable, and the long barrel similar to the old ones did not greatly increase their effectiveness when shooting[7]. Lighter and more convenient muskets were produced around the same 1630 in the German city of Suhl, which was achieved by shortening the barrel. Such a musket had a barrel of 102 cm, a total length of about 140 cm and a weight of approximately 4.5-4.7 kg.[7]. They initially fell into the hands of the Swedes, most likely, after the seizure of German arsenals[8]. In May 1632, in Rothenburg ob der Tauber, only a few Swedish soldiers were seen carrying such Zul muskets without bipods[8].

By the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th century, muskets began to be massively replaced with lighter weapons weighing about 5 kg and a caliber of 19-20 millimeters or less, first in France and then in other countries. At the same time, flintlocks began to be widely used, more reliable and easier to use than the old matchlocks, and bayonets - first in the form of a baguette inserted into the bore, later put on the barrel with a tube. All this together made it possible to equip the entire infantry with firearms, excluding from its composition the previously necessary pikemen - if necessary, the fusiliers entered into hand-to-hand combat, using guns with a bayonet attached, which acted in the manner of a short spear (with a musket this would be very difficult due to its weight) . At the same time, at first, muskets continued to be in service with individual soldiers as a heavier type of handgun, as well as on ships, but later they were completely replaced in these roles.

In Russia, this new type of lightweight weapon was first called fusee

- from

fr.

fusil , apparently through the Polish.

fuzja, and then, in the middle of the 18th century, renamed the gun

.

British gun model XVIII - trans. floor. 19th century, bearing the original designation Land Pattern Musket

.

Meanwhile, in some countries, in particular - in England with colonies, including the future USA - there was no change in terminology during the transition from muskets to guns; the new lightweight weapons were still called muskets. Thus, in relation to this period, English. musket corresponds to the Russian concept of “gun”

, since it designated precisely this type of weapon, real muskets in the original sense had not been made for a long time by that time; whereas in the 16th-17th centuries its correct translation would have been precisely the term “musket”. The same name was subsequently transferred to muzzle-loading smoothbore shotguns with a cap lock.

Moreover, even the general army rifled weapons that appeared in the mid-19th century, which in Russia until 1856 were called “screw guns”, and subsequently “rifles”, were initially designated in official English by the phrase “rifled musket”. This is exactly what, for example, in the USA during the Civil War they called mass-produced army muzzle-loading rifles, such as the Springfield M1855 and Pattern 1853 Enfield. This was due to the fact that before that the infantry had two types of weapons - relatively long guns - “muskets” (musket)

, faster-firing, suitable for hand-to-hand combat, and shorter for ease of loading rifles

(rifle

; in Russia they were called

shtutser)

, which fired much more accurately, but had a very low rate of fire due to the need to “drive” the bullet into the barrel, overcoming the resistance of the rifling , were of little use for hand-to-hand combat, and also cost several times more than smooth-bore guns.

After the advent of special bullets, such as the Minié bullet, and the development of mass production technologies, it became possible to combine in one mass model of weapons the positive qualities of previous “musket” guns (rate of fire, suitability for hand-to-hand combat) and rifles (combat accuracy) and equip them with all infantry; This model was initially called a “rifled musket.” musket

finally disappeared from the active vocabulary of the English and American military only with the transition to breech-loading rifles, in relation to which the more easily pronounceable word

rifle

.

It should also be remembered that in Italian official military terminology, “musket” is moschetto

- was the name of a weapon corresponding to the Russian term

“carbine”

, that is, a shortened type of gun or rifle.

For example, the Carcano carbine was in service as the Moschetto Mod.

1891 , and the Beretta M1938 submachine gun - as

Moschetto Automatico Beretta Mod.

1938 , that is, literally,

“Beretta automatic musket mod.

1938” (the correct translation in this case is

“automatic carbine”

, “automatic”).

Karl Russell - Guns, Muskets and Pistols of the New World. Firearms of the 17th-19th centuries

1 …

Karl Russell

Firearms of the New World. Guns, muskets and pistols of the 17th-19th centuries

Dedicated to the memory of my father, Alonzo Hartwell Russell (1834-1906), Captain of Company C, 19th Wisconsin Volunteers, 1861-1865

Preface

Fort Osage on the Mississippi River, 1808-1825. The westernmost U.S. military outpost until 1819 and the farthest west government trading post of the entire trading post system.

Firearms had a far greater influence in changing the primitive way of life of the Indians than any other item brought to America by white men. It is also true that these weapons played a decisive role in the conquest of the Indians, as well as in resolving contradictions between white newcomers in the initial period of their conquest of the New World. By the beginning of the 17th century, weapons had become an indispensable attribute of every American, and certain principles emerged regarding the acquisition and distribution of firearms and ammunition. Traditions of the design and production of weapons were recognizable in the American trading system already in its very early stages, and pronounced preferences for certain systems and models were demonstrated by both Indians and white newcomers. In this regard, the military in the early stages of American history was much less fastidious than private citizens. Several governments have tried to prohibit the sale of firearms to Indians, but all prohibition measures have had insignificant results; The arms import statistics are impressive even in these days of astronomical figures.

As this restless frontier, always flaring up with skirmishes, moved westward, Indian tribes abandoned their usual primitive weapons and were deprived of their ancestral characteristics. This process of change in their way of life continued for two hundred years, spreading in a strip across the entire continent. At the beginning of the 19th century, it reached the Pacific coast. Contrary to popular belief, the Indians of the colonial period were by no means proficient with the firearms they possessed at the time. In fact, they treated firearms with disdain and paid little attention to the characteristics and limits of their firepower; but still made their primitive muskets an effective instrument in matters of hunting and war. The gun-wielding Indian played a prominent role both in the white man's economic plans and in the tragic struggle for dominance that unfolded in the vast area north of Mexico. White politicians of those times did everything possible to ensure that firearms, gunpowder and bullets for them were always available to the aborigines.

The purpose of this book is to determine what firearms were used in America during the period of settlement of the eastern territories and the advance of the frontier to the west. Since the extraction and sale of furs largely determined the initial modus operandi[1] of the advance to the west, the weapons along the entire length of the frontier in the initial period were represented mainly by the firearms of traders and trappers[2]. After the military began to move westward along with traders or even ahead of them, it was their weapons that began to predominate in the movement of weapons to the west; Therefore, in this book we will pay attention to military weapons. Ammunition, which played a large and important role in the economy of the pioneers, will also find its place in it.

I am considering mainly the weapons used in the West in the first half of the 19th century, but since the weapons used by the first settlers on the eastern half of the continent were the forerunners of the weapons of Western armies, they also receive appropriate space in the book. And to make the story of weapons in the West more complete, it should be noted that the roots of the arms trade are traced in the manuscript to the appearance in the 17th century on the East Coast, as well as to the appearance of weapons on the St. Lawrence River. The foundations of the arms trade in the New World were laid by Dutch, French and especially English traders over the course of two centuries, after which the Americans began to operate in this area of business. Naturally, the book will pay attention to both European weapons and European influence.

The commercial and political aspects of the initial stage of the history of the Indians and firearms are full of high internal drama; yet even the most widely known pages of the history of the American West contain very little of the real truth about the arms trade. This book sometimes expresses ideas that are contrary to established views, but its purpose was to detail the knowledge in this area. Illustrations and related analytical descriptions will allow the reader to more fully imagine the corresponding weapon models. Some sections of the book are addressed specifically to the fraternity of weapons collectors, museum specialists and those archaeologists and historians who, much earlier than museum workers, were the first to extract various samples of weapons and their parts during excavations of historical sites. It is also my hope that the detailed analysis of the mechanisms and models of weapons will be of great help to all lovers of American history and reference material for a broader program of analysis of fragments of firearms recovered during archaeological work on sites that were once settlements of Indians. The book should also be useful to museum workers who organize materials on firearms for publication or exhibitions, and the manuscript should also be of interest to a wide range of gun collectors. I also have a special hope that the history of weapons, examined from this angle, will awaken public interest in the Mountain Men, their role in history, and will pay tribute to the labors of this “restless tribe.”

Karl Russell

Berkeley, California

Chapter 1

Arming American Indians

“Having traveled about nine leagues (40 km), the Indians [Montagnais and their allies] towards evening selected one of the prisoners they had captured, whom they passionately accused of the cruelties committed by them and their fellow tribesmen, and, informing him that he would pay for it in full measure, they ordered him to sing if he had the courage to do so. He began to sing, but as we listened to his song, we shuddered, for we imagined what would follow.

Meanwhile, our Indians built a large fire, and when it got hot, several people took burning branches from the fire and began to set fire to the poor victim in order to prepare him for even more cruel torture. Several times they gave their victim a break by dousing him with water. Then they tore out the poor fellow's nails and began to shoot burning brands at the tips of his fingers. Then they removed his scalp and placed a lump of some kind of resin over him, which, melting, released hot drops onto his scalped head. After all this, they opened his hands near the hands and, using sticks, began to forcefully pull out the veins from him, but, seeing that they could not do this, they simply cut them off. The poor victim let out terrible screams, and I was scared to look at his agony. Nevertheless, he endured all the torment so steadfastly that an outside observer could sometimes say that he was not in pain. From time to time the Indians asked me to take a flaming brand and do something similar to the victim. I replied that we do not treat prisoners so cruelly, but simply kill them immediately and if they wish me to shoot their victim with an arquebus, then I will be glad to do so. However, they did not allow me to save their prisoner from suffering. Therefore, I went as far away from them as possible, unable to contemplate these atrocities... When they saw my displeasure, they called me and ordered me to shoot the prisoner with an arquebus. Seeing that he was no longer aware of what was happening, I did just that and with one shot saved him from further torment...”

1 …

End of introductory passage

You can buy the book and

Read more

Want to know the price? YES I WANT TO

Notes

- Markevich V. E. Hand-held firearms. - St. Petersburg, 2005. - P. 31.

- Markevich V. E. Hand-held firearms. - St. Petersburg, 2005. - P. 40.

- Peter Krenn, Paul Kalaus, Bert Hall.

Material Culture and Military History: Test-Firing Early Modern Small Arms (English) // Material Culture Review / Revue de la culture matérielle. — 1995-06-06. - T. 42, issue. 1. - ISSN 1927-9264. - MILITARY LITERATURE - [Charters and laws - The doctrine and cunning of the military formation of infantry people [1647]]. militera.lib.ru. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Thomas Anbury.

“Here I cannot help observing to you, whether it proceeded from an idea of self-preservation, or natural instinct, but the soldiers greatly improved the mode they were taught in, as to expedition. For as soon as they had primed their pieces and put the cartridge into the barrel, instead of ramming it down with their rods, they struck the butt end of the piece upon the ground, and bringing it to the present, fired it off.” . - Dmitry Sosnitsky.

Ignatieva A.V. On the issue of the losses of the Ukrainian Cossacks of Ivan Mazepa during the siege and assault of the Turkish fortress Kazikermen in 1695 (Russian). slavica-petropolitana.spbu.ru. Retrieved May 12, 2018. - ↑ 1234

Ausrüstung und Bewaffnung von der Spätrenaissance bis zu den Armeen des Dreißigjährigen Krieges. Luntenschloßmuskete, Suhl um 1630 - https://www.engerisser.de/Bewaffnung/Luntenschlossmuskete.html - ↑ 12345

Richard Brzezinski. The Army of Gustavus Adolphus (1): Infantry. - Osprey Publishing, 1991. - p. 17. - William P. Guthrie. Battles of the Thirty Years War: From White Mountain to Nordlingen, 1618–1635. - Greenwood Press, 2002. - p. thirty.

Armor against bullets: what were they like and did they exist at all?

The competition between projectile and armor began not yesterday or even the day before yesterday, but from the very moment these two concepts were born. But early medieval European (and indeed Russian) armor was mainly intended to repel the blows of the weapon held in the hand. The issue of armor penetration of a bow is extremely controversial, and this is basically true, because the power of a bow directly depends on the physical strength of the archer. Crossbows... Well, anti-crossbow armor is unknown to historical science. The term itself is nonsense. The probability of running into a crossbowman, even during the years of the most widespread distribution of this weapon, was not so great, and it was simply ignored. They didn’t make any special armor for him.

Interlude

Everything changed... No, not the advent of firearms as such. And the appearance of granulated gunpowder, which burned consistently well and produced a large amount of powder gases. This is what made it possible to begin the mass production of muskets and arquebuses, suitable for mass - again - use on the battlefield. It was the beginning of the 16th century.

From time immemorial it has been this way: isolated cases of the use of one or another weapon at the front mean practically nothing. It's like... Well, the famous Me-262 is a Luftwaffe jet fighter.

For the Allied piston aircraft, he was an extremely unpleasant enemy, that’s a fact. In less than a year of production (1944-1945), only three jet Messers were shot down. But it didn’t fundamentally influence the course of hostilities, it just spoiled a lot of blood, that’s all...

It was exactly the same with gunpowder. At the dawn of its use, arrows from “hakovnitsa” on the battlefield decided little. Everything changed only when the opportunity arose to release musketeers and archers en masse onto the battlefields. By this point, the heavy musket bullet had become adept at piercing standard cuirasses.

No, it's certainly not a bullet. This is the work of a small gun

Bulletproof armor

They existed - that's a fact. They began to be made in the same 16th century as a symmetrical response to the musket and arquebus. Moreover, interestingly, such armor was of both plate and small-plate types - brigantines in the West and bakhtertsy in Russia.

Here, for example, is a bib from a Spanish cuirass with a bullet mark exactly opposite the heart:

Although, judging by the absence of other damage and the extremely precise location of this dent, this is not a battle wound, but a so-called "bullet test" There was such a practice in those years: after the armor was made, they shot at it with a pistol or musket. It was handed to the owner just like that - with a dent: it didn’t break through, they say!

Regarding this cuirass, I would assume that the “bullet test” was made from a pistol. The caliber is too small. Although I could be wrong.

But this armor has clearly been in a fierce battle:

As you can see, there are no breakthroughs. Although we cannot know from what distance and from what weapon they shot at him.

And here is a small-plate brigantine from the second half of the 16th century:

Now - a closer view from the inside:

Have you noticed how much overlap there is between the plates? This overlap is what it's all about. And the Russian bulletproof bomber had the same degree of overlap.

Now - about the most interesting...)

How much did the bulletproof armor weigh?

A lot of. In order not to bore the reader with boring numbers, I will say right away - twice, or even three times as usual. For comparison: an ordinary brigantine weighs 5-5.5 kg. This is if it is made for a person of average height and build. Cuirass - the same amount. Their steel thickness is approximately 1 mm.

But the bulletproof brigantine in the picture above weighs... 10.6 kg! She has one bib weighing 6.5 kilograms. Plate armor - bulletproof cuirass - had a mass within the same limits. Twice as heavy. Twice as thick.

Moreover, note: there were no guarantees of strength. Let’s say it can withstand a pistol, but a musket... Moreover, if the musketeer “to be safe” filled it with a one-and-a-half charge of gunpowder - and he could, this operation is risky, but possible... In short, there are no guarantees.

Why haven't they spread en masse?

Too heavy. Weight limit exceeded. Yes, purely theoretically, a person can wear a cuirass weighing 10-12 kg. Look, a modern anti-Kalashnikov class body armor weighs up to 16 kg, depending on the design. But you are forgetting one very important nuance...

A modern soldier rides to the battlefield. By train, car or other transport. And he only puts on his armored armor in battle. But the warrior of past centuries walked and carried most of his equipment himself, on his hump. In these conditions, even a needle weighs, you know... And he had a lot of equipment. There is not only armor and weapons, there are also a lot of things necessary purely for everyday life, without which you will be lost more likely than you will be shot on the battlefield.

True, this is not a soldier’s set, but a knight’s set, but note: household items are not included here. And it will be even harder with them.

Therefore, the most common bulletproof armor was among cavalry. This is not counting particularly high-ranking persons - kings, princes, magnates, etc. The horse will take you, you know, where it will go, the dumb beast...

But also this: as soon as the power of firearms grew even more (around the 18th century), anti-musket cuirasses were abandoned. They had to be made too thick, and therefore heavy. According to the unwritten standards of that time, the cuirassier's shell of the early 19th century (during the Napoleonic wars) had to withstand a pistol shot from 20 steps. The task of holding a rifle bullet was not set before him.

Literature

- Musket // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Efimov S.V., Rymsha S.S.

Weapons of Western Europe in the 15th-17th centuries. — Volume 2. Crossbows, artillery, handguns, combined and hunting weapons. - St. Petersburg: Atlant, 2009. - 384 p.: ill. — “Weapons Academy” series. — ISBN 978-5-98655-026-8. - Pocket William.

History of firearms: from ancient times to the twentieth century / Trans. from English M. G. Baryshnikova. - M.: ZAO "Tsentrpoligraf", 2006. - 300 p.: ill. — ISBN 5-9524-2320-5. - Markevich V. E.

Hand-held firearms. - St. Petersburg: Polygon, 2005. - 2nd ed. — 492 p.: ill. — Series “Military History Library”. — ISBN 5-89173-276-9. - Funken L., Funken F.

The Middle Ages. Renaissance era: Infantry - Cavalry - Artillery. - M.: LLC "AST"; Astrel, 2002. - 146 pp.: ill. — Series “Encyclopedia of Weapons and Military Costumes.” — ISBN 5-17-014796-1.

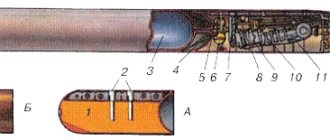

About the Great Patriotic War and more...

At the beginning of the 16th century. The Spanish infantry was considered the best in Europe. She was armed with new firearms - matchlock muskets These were long guns (total length - 180 cm, barrel - 140 cm, caliber - 20 mm), which had a stock with a figured butt. The butt widened towards the end, and a deep recess was made in the neck to fit the thumb of the right hand, which made it possible to hold the gun and simultaneously press the trigger lever. The muskets fired round lead bullets weighing 50 g, which pierced steel armor at a distance of 150 m.

When loading the musket, it was held in the left hand, and the gunpowder was poured from the charge into the barrel with the right. Then they crushed the gunpowder with a ramrod, after which they sent a bullet and wad into the barrel, compacting them with a ramrod. Having loaded the gun, the musketeer poured some gunpowder from the natruska (powder flask) onto the priming shelf, then inserted the burning end of the wick into the trigger and cocked it. Having placed the gun on the buffet stand, he took aim and, on command, pulled the trigger. Loading a musket and firing it was not easy - good training was required. At the very beginning of the 17th century. The Dutch commander-in-chief Moritz of Orange ordered a printed set of rules to be published for training soldiers. The book appeared in 1607 in Dutch, Danish and English, decorated with magnificent color engravings that illustrated the process of loading a musket, understandable even to the illiterate.

When firing, the musket was not pressed to the shoulder, but was held suspended by placing the barrel on a buffet stand and placing the cheek against the butt. Pressing the gun to your shoulder was out of the question because of the too strong recoil. For shooting, the musketeer carried gunpowder in special charges - wooden tubes with lids, covered with thin leather. Each of them contained a dose of gunpowder for one shot. Twelve such charges were suspended on a wide shoulder strap - a bandelier. The bullets were kept in a leather bag, and the wads were also there. The powder for the seed shelf was supposed to be finer, and it was carried in a separate powder flask - natrusk. The arrow was given a wick about one and a half meters long. It was worn rolled up and thrown over the left shoulder. Before the battle, one end of the fuse was set on fire, and the musketeer was forced to load the musket with the burning fuse in his hand, holding it with the fingers of his left hand.

Musket, ramrod, charger

The duration of loading the musket required a special formation of the infantry. The musketeers lined up in ranks in a quadrangle (square), which had ten or more rows in depth. Firing was carried out in volleys by each rank in turn. After the first salvo, the front rank split into two and went back, the second rank stepped forward, fired a salvo and also retreated. Then it was the turn of the third, fourth, etc. During this time, the first rank had time to reload the muskets. The square of musketeers continuously moved, resembling something crawling, which is why this formation was called “caracole” - “snail”. To protect against horsemen, pikemen stood on the flanks of the musketeer square. They stepped forward during the cavalry attack and blocked the path of the cavalry with pikes.

Cavalry by the middle of the 16th century. from a knightly one - armed only with edged weapons - it turned into a reitar one, which was armed with pistols or carbines. Cavalry firearms had a wheel ignition system. It was not easy for the horsemen to break through the ranks of pikemen, so the cavalry began to use caracal tactics similar to the infantry. Riders lined up in a column of four, up to 15-20 rows deep. At high speed the column approached the infantry, and each row successively fired a volley of pistols or carbines almost point-blank.

Caracoling continued until all the cavalrymen unloaded their pistols, and each of them could have two or even three pairs. Since the main weapon of the new cavalry was firearms, the cavalrymen were nicknamed pistoliers or carabinieri. The described tactics of military cavalry lasted until the end of the 17th century, and later the carabinieri turned into heavy cavalry, akin to the cuirassiers.

In all major wars of the 16th-17th centuries. the infantry fired matchlock muskets. The Spaniards fought America with them, and the Dutch defended their independence. In the second half of the 17th century. matchlock weapons are gradually being replaced by flint weapons in the infantry. And then in the cavalry: they began to use flintlock pistols and carbines instead of wheeled ones. The cavalry, armed with flintlocks, transformed into dragoons. This was the name given to horsemen who, dismounted, could fight like infantry. The main weapons of the dragoons were shortened rifles. Occasionally they had to use edged weapons - broadswords.

In Russia they also used matchlock guns, similar to European muskets, but they were much shorter. In the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, arquebuses from the late 16th century have been preserved. They have three types of butts: musket, carbine and arquebus (without a neck). The total length of the guns reached 115 cm, the barrel length was 70 cm with a caliber of 16 mm. Russian archers of the 16th-16th centuries were armed with such arquebuses. In the second quarter of the 17th century. part of the Russian infantry (regiments of the “new order”) fired from European-made muskets, but later they were abandoned in favor of flint muskets.

Around the same time, in the second quarter of the 17th century, paper cartridges appeared instead of chargers. These were rolled paper tubes containing a charge of gunpowder and a bullet. The musketeer had to bite off the corner of the “cartridge”, pour gunpowder into the barrel, and then send the bullet there along with the paper shell, which played the role of a wad. The cartridges were carried in a leather pouch in the amount of 30 pieces.

A radical reform of the infantry system in Europe occurred during the Thirty Years' War (1617-1647). The Swedish king Gustav II Adolf (1611-1632) introduced an improved musket into his infantry: it weighed no more than 4.5 kg with a total length of 150 cm. The weight of the bullet and gunpowder in the charge was reduced, which changed the shooting style. Muskets began to be made with more comfortable butts: now they could be rested on the shoulder, as recoil was reduced. There was no longer any need for a buffet.

The trigger lever was replaced with a trigger with a trigger guard. Gustav II's infantry was lined up six rows deep, with significant gaps between the rows. This made it possible at the right time to double the ranks and change into three ranks, which increased the mobility of the infantry. The new formation was tested during the Thirty Years' War, and then all European commanders rated it as the most convenient. In the second half of the 17th century. the pikemen were abolished. The musket was given a bayonet, and now the soldiers could fight off the horseman on their own.

Infantry weapons with a flintlock first appeared in France in the mid-17th century. From there the name of the infantry rifle “fusey” (from the French fusil - “gun”) spread. Soldiers armed with fusiliers began to be called fusiliers. In order to handle the fusee there was still a lot from matchlock muskets, in particular loading from a paper cartridge. The bayonet and butts also at first resembled muskets.

The invention of a more reliable and secure flintlock contributed to the development of military weapons. During the second half of the 17th century. The main types of military guns of the 18th-19th centuries were created. At that time, military leaders believed that each branch of the army, in addition to different uniforms, also required different guns. Because of this strange representation of the army of the late 17th century. In addition to infantry rifles, they were armed with a whole series of similar rifles, but with differences in size, caliber, presence or absence of a bayonet and other details.

In the armies of almost all European countries, guns were divided into infantry, dragoon, cuirassier, sapper, huntsman, non-commissioned officer, etc. Carbines were also divided into: cuirassier, hussar, blunderbusses and fittings. All of them, with the exception of blunderbusses and fittings, were of a similar design. A thin-walled barrel with a smooth (without rifling) bore was placed in a long fore-end. Flintlock - French battery system. The rifle butt had a convenient shape with a round neck. The device of the gun (fastening and protecting parts) was iron. The gun was equipped with a triangular bayonet on a curved sleeve. The ramrod was retracted into a long channel made in the forend under the barrel. The barrel was attached to the forend on transverse pins, and the lock in the stock was attached to two through screws. The stock was solid, that is, the forearm and butt were made from one piece of wood, usually birch. Such infantry and cavalry weapons were also used in the 18th century.

The main type of gun in the infantry was the soldier's fusee, which had a total length without a bayonet of 145 cm (with a bayonet - 180 cm), a barrel length of 100 cm, and a caliber of 19 mm. The weight of the fusée depended on the wood of the stock (birch, oak, ash, elm) and amounted to 5-5.5 kg. Infantry officers and non-commissioned officers had their own lightweight fusees, which also differed from soldiers' ones in finishing. Depending on the rank of the officer, she could be quite rich. In the second half of the 18th century. officers' fuses were standardized. Their total length without bayonet was now 139.5 cm, and their caliber was 17.3 mm.

Top: double-barreled shotgun of the Austrian border guards. Length – 1055 mm, caliber – 14.8 mm. Bottom: Austrian trombone. Around 1780

In the grenadier regiments, the first rank consisted of grenadiers throwing hand explosive grenades at the enemy. They were usually thrown by hand, but there were special mortars . They had a butt, like a fusee, and a short barrel (20-30 cm long) with a barrel in the form of a cauldron-shaped rasp (extension of the barrel at the muzzle) of large diameter. The charge was ignited using a fusey-type flintlock. Mortars differed in the weight of the grenades thrown: one-pound (barrel caliber - 49 mm) and three-pound (barrel caliber - 72-74 mm).

Grenadier of the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment (1705-1720). On the right is an officer's grenadier hat.

In the middle of the 18th century, teams of rangers - shooters operating in loose formation - appeared in European armies. Since the rangers were selected to be of short stature, they were entitled to shortened ranger fusées: total length without bayonet - 132 cm, barrel length - 92 cm; they had a caliber of 19 mm. Even when the teams of rangers transformed into ranger regiments, their main armament remained smooth-bore fuses, and rifled fittings were issued only to the forward chains.

A Russian private dragoon on horseback in full combat uniform and weapons. XVIII century

The main weapon in the dragoon cavalry were short dragoon fuses (length without bayonet - 140 cm, caliber - 17.3 mm). Through the so-called running bracket on the fusel's stock, it was attached to the sling using a carbine hook (that's why the shortened gun began to be called a carbine). In the second half of the 18th century. Cuirassier, hussar, sapper and equestrian pioneer carbines (for mounted reconnaissance) were adopted. Their length without bayonet was 139 cm, barrel length - 86 cm, caliber - 17.3 mm. When riding a horse, the fusee hung on the right side of the saddle.

In the middle of the 18th century. In almost all European armies, fuses received a copper device instead of iron. Copper parts did not rust and gave the guns an elegant look. In addition, the barrel mount on studs was replaced with a French version of the connection using stock rings. This was convenient for disassembling the gun and cheaper to manufacture. Improvement of guns in the second half of the 18th century. came down mainly to achieving uniformity and interchangeability of individual parts. By the end of the century, the main parts of guns - the barrel, lock and stock - could fit together without additional adjustment.

Engraving from the book “The Perfect German Soldier” by H. F. von Fleming, 1726: firing in ranks

Simpler and faster loading of a flintlock gun led to the widespread spread of the three-rank system, introduced by Gustav II Adolf. In the 18th century Instead of a deep square, a linear structure began to predominate. At the same time, infantry tactics also changed significantly. Each of the three ranks fired salvos in turn. The entire line also went on the attack, and it was strictly necessary not to break the formation. Because of this, they tried to fight on a flat plain. After the shot, the soldiers in the front ranks squatted on one knee, and the rear ranks opened fire over their heads. An active supporter of the linear system was the Prussian king Frederick II the Great (1740-1786). Drill and strict order reigned in his army. Since it was not always possible to build three long lines on rough terrain, they sometimes fired in smaller units - plutongs (platoons). They were lined up in a ledge, and firing was carried out “rolling” from one flank to the other.

Blunderbuss - short fusées with a flap, i.e. with a bell - were quite widespread. They were used in the navy, in the defense of fortresses and in cavalry. Cavalry blunderbusses were light, portable weapons no more than a meter long, with a spread of 35 to 45 mm. The purpose of blunderbusses is to shoot grapeshot bullets at close range. They were used to a limited extent as additional weapons, several per squadron.

All fusees were smooth-bore weapons and could shoot no further than 300 steps (220 m), but for an accurate hit they opened fire from 100 steps. The bullet's penetrating ability made it possible to pierce an iron cuirass at a distance of 50 m. The soldiers continued to use paper cartridges for loading. The rate of fire of fusilier units was 2-3 salvoes per minute without aiming, and at the beginning of the 19th century. increased to 4 salvos. Some shooters managed to fire up to 5-6 shots per minute without aiming. The rate of fire of rifled weapons at that time was no more than one shot per minute.

However, by the end of the 18th century. fittings - appeared in European armies . Although it took a lot of time to load the rifle, it fired much more accurately. A distinctive feature of the fittings were short faceted barrels (70-75 cm). Inside the barrel there were eight helical grooves. Sighting devices were placed on the trunks - a rear sight and a front sight. The cavalry used shortened cavalry fittings (16 pieces per squadron). But cuirassiers, dragoons and lancers armed with guns were called carabinieri in the old way.

Left to right: British flintlock military "long musket", issued in Birmingham in 1747. Length - 1565 mm, caliber - 19 mm. German infantry flintlock infantry rifle of the first half of the 18th century. Length (with bayonet) – 1760 mm, caliber – 19mm. British infantry flintlock rifle of the second half of the 18th century. Length – 1720 mm, caliber – 16 mm. Prussian infantry flintlock rifle 1722 - 1740. Length – 1565 mm, caliber – 19.8 mm.

The fusees of most European countries were similar in design, although they were slightly different in appearance. For example, in Prussia in 1730-1760. Infantry fuses had a special type of stock called a “cow hoof.” It had a very narrow stock neck and a long butt comb. In Russia in 1730-1740. Similar butts were made, then they were abandoned in favor of more durable French butts.

At the beginning of the 19th century. almost all countries have carried out reforms that unify handguns. For example, in France this happened in 1803, and in Russia in 1808. The shape of some parts changed. The iron seed shelf was replaced with a bronze one. They began to make the trigger with a ring under the jaws for strength. To reduce recoil, the butt was given a beveled shape, and instead of a notch, a cheek appeared on the left side of the butt. The front sight began to be soldered on the barrel, and not on the stock ring. The infantry rifle was shortened, but the length of the bayonet was increased. In Russia, the name “fusey” replaced the word “gun”.

In the 20-30s. XIX century a capsule lock already existed . Despite the obvious advantages of percussion weapons (no misfires, shooting in any weather), the military was in no hurry to introduce it into armies. In 1835, Austria became the first country to introduce percussion cap infantry weapons. Next, in 1842, was France, and then Russia (1843-1844). Initially, all percussion weapons were converted from flint. But later they began to produce infantry and cavalry weapons with a capsule lock.

In terms of appearance and tactical and technical data, percussion rifles - infantry, dragoon and cavalry - were almost no different from flintlock rifles. The caliber remained the same (17-18 mm), the length without bayonet was 140-145 cm, the weight of the guns remained within 4-5 kg. Loading of percussion weapons was still carried out from the muzzle. But the preparation of the weapon for firing still accelerated. Instead of the troublesome filling of gunpowder onto the priming shelf, the primer was now quickly placed on the fire tube. Misfires were significantly reduced and there were no problems shooting in wet weather. The shot has become more reliable. Its effectiveness remained the same - no more than 300 steps. As experienced shooting at that time showed, good shooters, aiming at a tall target from 300 steps, gave only 20% hits, and from 150 steps - 60% hits. In the armies, there was a division of the same type of rifles for different types of troops: infantry, dragoon, sapper, Cossack and cavalry carbines.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the linear formation gave way to a loose formation combined with an attack in columns. Despite the reliability of the new percussion weapon, commanders relied heavily on bayonet attacks. This was due both to the inaccuracy of smoothbore rifles and to the lack of shooting skills among the soldiers. They are used to firing in volleys without aiming. The officers, in the old fashioned way, paid the main attention to the clarity of the formation and the consistency of the salvo production. The saying “The bullet is a fool, but the bayonet is a fine fellow” remained relevant in the era of percussion muzzle-loading weapons. Serious changes in battle tactics occurred only with the massive introduction of rifles, or rifles, into armies.

Based on materials from the book “Firearms,” ed. group: S. Kuznetsov, E. Evlakhovich, I. Ivanova, M., Avanta+, Astrel, 2008, p. 44-53.

All about double-barreled shotguns with vertically coupled barrels

DOUBLE-BARREL SHOTS

with vertically paired trunks

Models:

BDF 2000E, 2001E, 2002E BBF 2010E, 2011E, 2012E BDB 2020E, 2021E, 2022E

HANDLING GUIDE

INTRODUCTION

Double-barreled shotguns with vertically coupled barrels (Bockgewehre) are the most popular among the hunting weapons in use. These guns allow for a variety of design options, so they can satisfy the diverse needs of professional users.

The range of weapons produced by SUHL includes: BDF - Bockdoppelflints

- double-barreled shotguns with vertically paired smooth barrels for hunting small game.

BDF - Bokdoppelflints

- double-barreled shotguns with vertically paired smooth barrels for sport shooting (on trench and round stands).

BBF - Bokbyuksflint

- double-barreled shotguns with vertically paired barrels: one barrel is smooth, the other is rifled.

Designed for mixed hunting (small and large game). BDB - Bockdoppelbuks

- double-barreled shotguns with vertically paired rifled barrels for hunting big game.

-Combined guns

(one gun with one or more additional interchangeable barrels).

The practice of using this type of shotgun has shown that of the entire variety of hunting weapons, double-barreled shotguns with vertically paired barrels ultimately remain the most preferable.

This is confirmed by three main criteria: 1. A high, narrow fore-end makes it easy to manipulate the gun and protects your hands from the effects of hot or supercooled barrels. 2. The vertical (one above the other) arrangement of the barrels reduces the width of the weapon and at the same time increases the field of view, since during shooting targets are viewed over one barrel. 3. The shooting error resulting from the recoil of the gun is reduced, because the recoil force acts in the vertical plane.

In view of these advantages, international sport shooting competitions are, in principle, held only with the use of bokdoppelflints (with the exception of certain cases of the use of self-loading shotguns for shooting on round stands).

For fans of clay pigeon shooting at flying saucers, as well as hunters improving their shooting skills (hunting training), the bokdoppelflint in a universal sporting and hunting version is the gun that is really required. If you additionally acquire one or two interchangeable barrels, you will have the ideal weapon for a real hunter.

1. TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICS

1.1. Trunks

Barrel caliber

(see also gun passport)

- For the Bokdoppelflint smoothbore shotgun. as well as for replacement barrels for it: 12/70, 12/76 or 20/76. Special caliber - at customer's request.

- For the Bokbyuksflint gun, as well as for interchangeable barrels for it: a smooth barrel of caliber - 12/70, 12/76, or 20/76 is combined with a rifled barrel with a caliber within the weapon program.

- For shotguns with Bokdoppelbücks rifled barrels, as well as for replacement barrels for them - within the limits of the weapons program.

Distinctive features of the trunks:

- Special barrel steel.

- Chokes (chokes) - at the customer's request (see the gun's passport).

- Ejection of cartridges: using spring ejectors, which can be switched off if desired.

1.2. Mechanism system

Models: 2000E, 2010E, 2020E 2001E, 2011E, 2021E

- Compact bolt box with insertable front part.

- Kersten lock with side stop (disconnector).

- Modified Anson impact mechanism with safety stops.

- Self-cocking mechanism using pushers.

- Standard descenders:

1) one trigger without a shot sequence switch. 2) one trigger: with shot sequence switch (optional); 3) double trigger (two triggers).

- Individual drummers;

- Security: manual fuse. When the shutter lock is open, the shutter impact mechanism cannot be activated.

Model 2002E, 2012E, 2022E

The bolt box has attached side plates on both sides.

1.3. Lodge

- The stock is made of selected walnut wood.

- The shape of the stock is established for gun models, but can be changed at the request of the customer, as well as the dimensions of the stock.

- Narrow composite forend. The upper part of the forend is fixedly attached to the gun barrels, the lower (removable) part is attached to the barrel with a latch.

- Rough notches on the surfaces of the stock and fore-end.

- Elegant, gracefully designed interface of the stock with the bolt box, complemented by the wide surfaces of the side plates.

- Attaching the stock from the rear using a coupling bolt.

- Plastic butt pad and cheek piece.

2. ASSEMBLY OF THE GUN (after unpacking)

The gun consists of the following main parts (Fig. 1):

- Barrel block (1)

- Forend (detachable part) (2)

- Bolt box with butt (3)

Connecting parts

Shotguns are delivered to customers disassembled and include:

- Barrel block with forend installed

- Bolt box with butt

The parts of the gun are connected in the following order:

1. Separate the forend from the barrels (Fig. 2):

- Take the trunks (1) in your left hand,

- Using the index finger of your right hand, open the forend latch (2) and, using light pressure, separate the forend from the barrels.

2. Attach the barrels to the bolt box (Fig. 3):

Before attaching the barrels to the bolt box, make sure that the cartridge ejectors are pushed out of the barrel block by the springs until they stop.

Warning:

Spring cartridge ejectors can be in two different positions when separating the forend:

- the ejectors are completely extended from the grooves and their head parts rest on the thrust screws of the longitudinal tires of the barrel block;

- the ejectors are only partially extended and stopped in the gases of the forend.

If the ejectors are stuck in the grooves, they must be released by pressing on both of their heads. This will make it easier to separate the forend and prevent possible damage to the surfaces.

With your left hand, grasp the barrels (1) close to the under-barrel hooks, while it is advisable to clamp the muzzle ends of the barrels between your knees. With your right hand, grasp the handle of the butt with the bolt box (2) and insert the barrels into the bolt box so that the hinge surfaces of the under-barrel hook are adjacent to the hinged axis of the bolt box. Use your left index finger to maintain the connection.

With the thumb of your right hand, press the shutter lever (3) and move it to the right until it stops. In this position, the shutter lever is automatically held in place by a latch. At the same time, turn the bolt box with the butt until it fits snugly against the barrel block, while making sure that the protrusions of the ejector pushers (4) fit into the grooves of the receiver and that the pushers are pressed from behind. When the receiver rests against the barrel block, it releases the bolt lever stop and the bolt lever should return to its center position on its own. If this does not happen, then lightly press the lever with your hand and put it in place.

3. Attach the handguard (Fig. 5):

Take the gun in your left hand and place it with the butt down. Turn the safety trigger guard to the right, and the muzzles of the barrels upward.

With your right hand, install the hinge surfaces of the forend onto the corresponding hinge surfaces of the bolt box. When aligning the hinge surfaces, the ends of the cocking levers must fit into the corresponding cutouts in the forend.

Press the forend against the barrel until it is completely seated. If necessary, lightly hit the fore-end with the palm of your hand below the latch flap. The forend latch valve should fit into the forend recess on its own. If necessary, lightly press the valve with your hand.

Turning off the ejectors (Fig. 4): (for specially designed guns)

- Separate the forend from the barrels. Both switch fingers, located in the metal part of the forend, rotate 90°.

- The slot of the switch finger is located along the axis of the gun - the ejector is turned on.

- The slot of the switch finger is located across the gun - the ejector is turned off.

3. COCKING AND LOADING THE GUN

To cock the trigger mechanism and load the gun, perform the following operations:

- Take the gun with your right hand by the butt handle, and grab the fore-end with your left hand. Point the trunks forward and slightly downward.

- Using your right thumb, open the bolt by pressing the bolt lever to the right.

- With your right hand, fold down the bolt box with the butt until it stops.

- Insert the cartridges into the chambers of the barrels that are slightly tilted downwards.

- With your right hand, turn the bolt box with the butt in the opposite direction until it fits snugly against the barrel block.

- The shutter lever should return to its original position on its own. If the lever does not return, turn it by hand until the bolt closes completely.

Important:

Before loading the gun, make sure that there is no grease or foreign objects left in the gun barrels. Protect the gun from impacts, do not use force! Use only the ammunition intended for the gun, as indicated on the barrel!

4. FUSE OPERATION

The safety lever is located on the buttstock handle. The gun is put on safety manually by moving the safety lever back. The gun is on safety when the safety slide is in the rear position, and the letter S is clearly visible in front of the slide. To remove the gun from the safety, the safety slide must be moved all the way forward by hand. When the shutter lock is open (the shutter lever is held by a stopper and remains in the open position), no shot is possible.

5. DISCHARGE DEVICES

Bockdoppelflint smoothbore shotguns are supplied as standard with one or two triggers, or one trigger with or without a shot sequence switch.

Shotguns with rifled barrels - Bokbkzhsflints and Bokdoppelbyuks, as well as combined shotguns with interchangeable barrels - can have two triggers, with the front trigger simultaneously serving as a trigger regulator.

Double escapement

The front trigger is designed for the lower barrel. The rear trigger is designed for the upper barrel.

Single escapement

- One trigger without switch. Sequence of shots: lower barrel - upper barrel.

- One trigger with a switch (switching is carried out by an eccentric located next to the trigger).

Sequence of shots:

- eccentric on the right: lower barrel - upper barrel;

- eccentric on the left: upper barrel - lower barrel.

Double release with regulator (plug)

In this embodiment, the front trigger, designed for the lower barrel, can be used as a regular one or with adjustable trigger force.

The rear trigger, designed for the upper barrel, is used as a regular one (without adjustment). Adjusting the front trigger for firing from a rifled barrel (Fig. 6). Aimed shooting over long distances (about 100 m), in addition to the training of the shooter, also requires appropriate technical capabilities of the weapon, which would ensure good results. For this purpose, trigger regulators are used, which significantly help shooters when shooting from rifled barrels.

To engage and cock the trigger control, the front trigger is pushed forward until it noticeably moves and locks. The trigger moved forward is under the action of a special spring. Now just a small movement, respectively a slight pressure of the finger, is enough for the trigger to disengage. Further necessary movement of the trigger occurs automatically and causes a shot.

The operation of the trigger control can be adjusted using the adjustment screw located on the front trigger. Screwing in the screw makes the release easier, unscrewing makes it harder.

Attention!

Adjustment of the trigger regulator should only be done by a gunsmith.

Warning:

First, put the gun on the safety, then cock the trigger!

If the shot does not fire when the regulator is cocked, then first put the gun on the safety, then carefully grasp the trigger with your thumb and forefinger and slowly pull it back (remove the regulator from cocking). Keep the muzzle of the gun pointed in a safe direction during this operation. Then open the gun with the safety on to remove the cartridges!

6. SIGHTS

Each block of barrels has corresponding sighting devices.

On Bokdoppelflint smoothbore shotguns, as well as on replacement barrels for them, there is a matte sighting rib (solid or ventilated) with a front mother-of-pearl front sight (on some barrels there is also a middle front sight).

Shotguns with combined barrels - Bokbyuksflints, as well as interchangeable barrels for them, have a matte sighting rib with a folding plate rear sight and a front adjustable pearl front sight.

Rifled shotguns-Bokdoppelbuks, as well as interchangeable barrels for them, have a choice of either a permanent rear sight and an adjustable pearl front sight, mounted on separate bases, or a solid saddle-shaped sighting bar with a constant rear sight and an adjustable mother-of-pearl front sight. If an optical sight is installed on the gun, then the above open sights can be completely replaced, or, if desired, used in parallel.

7. TESTING THE GUN

Smoothbore guns

The muzzle constrictions of the barrels are made in such a way that when firing from a gun, the required percentage of shot hits is ensured. The production of the choke constrictions was carried out with heat treatment of the metal. Test shots from the gun were fired from a distance of 35 m from both barrels (for further information, see the gun's passport).

Shotguns with barrels for sport shooting on round stands (Skeet) were tested from a distance of 20 m. Smoothbore shotguns are not tested with cartridges with bullet charges, unless this is clearly specified in the customer's requirement.

Shotguns with rifled barrels

Shotguns with rifled barrels were shot from a distance of 100 m with the ammunition specified in the gun's passport. The results of the zeroing can be seen from the shooting map (Anshussbogen) attached to the passport. It should be borne in mind that when zeroing, the aiming point for open sights was taken “under the apple”, and for optical sights - “in the middle of the target”.

If other types of ammunition are used, or ammunition from other manufacturers than those indicated in the gun's passport, the position of the impact points may change. However, this change can be adjusted by a gunsmith at any time.

When shooting from shotguns with two rifled barrels (Bockdoppelbuks), it should be taken into account that the zeroing results attached to the shotgun passport were obtained for the following conditions:

- The order of shots was always lower barrel-upper barrel. (On the shooting map, hits from the lower barrel are marked with odd numbers, and hits from the upper barrel are marked with even numbers).

- The time intervals between shots from the lower and upper barrels ranged from 5 to 10 seconds. If these intervals were larger or smaller, the shooting results would be somewhat different.

- All pairs of hit points were obtained by shooting from cold barrels.

- For shotguns with different-caliber rifled barrels, each barrel is sighted separately.

8. SAFETY RULES

- Carefully study the rules for handling your gun!

- Keep an eye on the gun at all times when it is loaded and ready to fire!

- Use only ammunition sold in specialized stores. Unusable ammunition will damage your gun and put you at risk!

- Use only ammunition that is compatible with the caliber of your gun.

- Whenever handling a gun, keep the barrel of the gun pointed in a safe direction, but never towards people!

- Check the gun barrels for cleanliness from any blockages!

- Always load your gun immediately before hunting!

- Never transport a loaded gun!

- Only put your finger on the trigger when you see the target and are about to shoot at it!

- Be attentive to what is behind the target!

- Never leave your gun and ammunition unattended!

- Store your gun and ammunition separately in separate places!

- Protect the gun from access by unauthorized persons!

- Unload your gun:

- before climbing hills and when descending from them;

- before entering vehicles;

- before overcoming obstacles.

- If a misfire occurs, open the gun only after one minute. Beware of cartridge ignition!

9. SHOOTING

You can shoot a gun only after thoroughly making sure that

- that you clearly see the goal;

- that there is no disturbance around and that no one will be harmed;

- that there are no living creatures, buildings, roads, etc. in the adjacent territory within the range of the shot.

If safety conditions are met, aim the gun at the target and move the safety lever to the forward position (firing position).

By pressing the appropriate trigger. You can fire a shot; if you do not fire, then immediately put the gun on the safety again by moving the safety slide back. To shoot with a reduced trigger pull, without removing the gun from the safety, cock the trigger control on the front trigger.

Attention!

When the trigger control is cocked, do not fire by pulling the rear trigger first! This creates the danger of a double shot (from both barrels). When the trigger control is cocked, the stability of the front trigger is significantly reduced.

10. UNLOADING, DISCOCKING AND DISASSEMBLING THE GUN

10.1 Unloading and de-cocking

At the end of firing, the gun opens to remove spent cartridges or unspent cartridges, then closes again. In this case, the trigger mechanism is automatically cocked. To ensure that the mainsprings of the trigger mechanism are not under unnecessary tension, the mechanism should be decocked.

This is done in the following order: after ejecting spent cartridges or removing unspent cartridges, uncharged buffer cartridges (false cartridges) are inserted into the chambers of the barrels. Then the gun is closed, removed from the safety lock and decocked by pressing the triggers.

10.2 Disassembling the gun

For cleaning, as well as for packaging (for the purpose of shipping or transportation), the gun must be divided into:

- Barrels with attached forend

- Bolt box with butt.

This is done in the following sequence: remove the gun from cocking as described above. Separate the forend from the barrel block (Fig. 7)

Place the gun firmly on the butt and grasp the barrels with your left hand. Using the index finger of your right hand, open the forend latch valve and, using light hand pressure, separate the forend.

Separation of trunks (Fig.

- With your left hand, grasp the barrels between the fore-end latch and the bolt box.

- Turn the muzzles of the trunks down and press them between the heads.

- With your right hand, grasp the neck of the stock and, pressing the bolt lever to the right with your thumb until it stops, turn the bolt box and disconnect it from the barrels.

- To return the shutter lever to the middle position, press the lock button located on the front surface of the bolt box.

Installing the forend on the barrels (Fig. 9)

- Take the trunks in your left hand and place them on a stable wooden block.

- Grasp the fore-end with your left hand and press it against the barrels until it fits completely. If necessary, tighten the fore-end with a light blow of the palm of your hand below the latch valve.

- The latch valve itself should be completely seated in the recess of the forend. If necessary, push the valve in by hand.

10.3. Combination shotguns

If some other barrels are adapted to the gun, the so-called. interchangeable barrels, then such a gun is called a combined gun. Installation and removal of replacement barrels is carried out as described above.

Warning:

If a combined gun with ejectors is equipped with a barrel pair with only cartridge ejectors, then when installing such barrels on the gun, the ejector devices must be turned off.

All combination shotguns are serviced according to the same rules as the main model.

11. GUN CARE

11.1 Cleaning the gun

Immediately after using the gun, it is necessary to clean the barrels to remove all deposited powder carbon from them before it can intensively affect the barrel steel. For this purpose, cleaning rods are used, wooden, plastic or copper (but not steel) with an eye into which cleaning rags in the form of textile strips are threaded. Keep in mind that for cleaning rifled barrels, special cleaning rods must be used that correspond to the caliber and bore diameter of the barrel. Do not make the rag swab too thick, since a cleaning rod then pushed into the barrel with great force can damage the inner surface of the barrel, which subsequently can significantly reduce shooting results, especially from rifled barrels.

If a swab from a rag does not remove barrel deposits (lead), then use a cleaning rod with a special copper wire brush for cleaning. Be careful when cleaning rifled barrels with brushes!

If you are unable to clean the barrels using this method, contact a gunsmith for help. Cleaning the outer metal surfaces of the gun is done with linen rags (do not use any wool or synthetic materials for this).

To ensure that all surfaces of the gun are thoroughly cleaned, completely remove moisture from them. It is also preferable to remove lubricating oil from exposed surfaces.

Warning:

Hand sweat is often the cause of rust. For those prone to sweating, keep this in mind.

There is a simple way to prevent this: after cleaning, the gun is held by the butt and all steel surfaces are wiped a second time. Without further touching the steel parts, the gun is then lubricated.

11.2 Lubricating the gun.

The gun must be thoroughly cleaned before lubrication. To lubricate the gun, well-known gun oil is used, purified from resinous and acidic impurities. Technical Vaseline also deserves attention.

First, the internal surfaces of the barrels are lubricated, for which a clean, oil-soaked cotton swab is pushed with a cleaning rod through the bores. All external surfaces of metal parts are lubricated with a linen cloth soaked in oil. You can also spray surfaces from oil cans, if they are commercially available. All steel parts must always be coated with a thin layer of lubricant; Particular attention should be paid to rubbing and hinged parts.

The butt and fore-end are lubricated with special oil for butts. Repeated cleaning of the barrel bores the next day after lubrication, the so-called “Nachschlag,” has a beneficial effect on the technical condition of the gun. This repeated cleaning completely removes any remaining powder residue from the barrels.

If the gun is not used for a long time, it is recommended to periodically check the technical condition at certain intervals.

Important!

- Do not leave the gun with the firing mechanism cocked!

- Before each shooting, wipe the barrel bores dry to remove any grease!

At certain intervals, parts of the trigger mechanism are also cleaned and lubricated. It is advisable to carry out this work not independently, but under the supervision of a gunsmith.

This way, you can safely welcome the next hunting season.

Flintlock reversal gun (No. 01355)

Double-barreled hunting shotgun with a rotating block of barrels and a flintlock; master Antoine Devino, Paris, France, 1740 -1750.

Overall length 1144 mm Barrel length 741 mm Caliber 15 mm

DESCRIPTION

The barrels are steel, light gray blued; round to the middle, then pentagonal; in the middle there are three decorative belts; the bores are smooth. The trunks are connected in a vertical plane into a single block, which is equipped with wooden slats on the sides. A steel ramrod bushing and the mouth of the ramrod are screwed onto one strip, and only the groove is screwed onto the other strip. In the rolled part of both barrels there is an inscription inlaid with gold “DEVINEAU ARQ ER DU ROY A PARIS”

The barrel breech is decorated with a strip of gold inlay. There is a seed hole on the right side of the breech of each barrel. The barrel block is connected to the stock on a longitudinal axis, on which it can rotate when the lock is pressed. The barrel block at the end is closed with a hexagonal plate, which connects to the locking block in the stock and through which the mentioned axis passes. On the right and left sides of the receiver block there are the front parts of the locking boards, on which the seed shelves, flint and bending springs are mounted. The right side of the stock has the back of the keyplate cut into it. On the front of the axis there is an S-shaped trigger with a solid round screw head and an upper movable jaw, decorated with light engraving with floral patterns. The keyplate is engraved with images of trees, a dog and a snarling wolf pinning down another dog. Under the picture there is the inscription “DE VINEAU a PARIS”. a ramrod, the charge in which is ignited by seed powder from sparks generated when a flint hits a flint (flintlock).

According to its intended purpose, this item can be considered a hunting shotgun, intended for shooting shotguns when hunting birds and small animals. Weapons of this system became widespread in the second half of the 17th century. and its characteristic feature was a block of rotary barrels, which had a locking plate on each side of the barrel under the seed hole, on which only the seed shelf, flint and bending spring were mounted. The striking part of the lock with the trigger on the locking board, as a rule, was one and crashed into the stock behind the block of barrels. When muzzle loading, such a system made it possible to fire two shots in a row, using a lightweight version of the mechanism that had the striking part of the lock on only one side. Both barrels were loaded simultaneously and seed powder was poured onto both shelves. After firing from the upper barrel, the shooter pressed the safety bracket stopper, turned over the block of barrels, and the loaded lower barrel with its shelf and flint was placed under the trigger. We could shoot again.

The lock is secured in the stock with one through screw. On the left side of the stock there is a steel figured face underneath it, decorated with engraved scrolls. In front of the lock cylinder, at the end of the block, a curved plate is attached to a screw, covering the lower flint. The stock has a narrow round neck and a wide butt with a high comb. The neck is straight, the butt has hollows on both sides. The end of the butt is closed with a steel butt plate with two screws. At the top, the back of the head is placed on a stock in the form of figured images of a vase and stylized leaves. The back of the head is decorated with light engraving with floral-geometric patterns. On top of the neck of the stock is an oval white metal medallion with the engraved initials “BE”. A steel safety bracket with a long shank and a base is embedded in the bottom of the stock under the lock. The safety bracket in the front part has a vertical round rod that fits inside the base of the bracket, serving as a barrel stopper. On the bottom of the bracket there is an engraved floral-geometric ornament. An almost straight trigger protrudes from the base of the guard through a slot. Wooden ramrod with a conical bone tip.

DEFINITION